The Lean Post / Articles / How the A3 Came to Be Toyota’s Go-To Management Process for Knowledge Work (intro by John Shook)

Problem Solving

How the A3 Came to Be Toyota’s Go-To Management Process for Knowledge Work (intro by John Shook)

By Isao Yoshino

August 2, 2016

A3 thinking is synonymous with Toyota. Yet many often wonder how exactly this happened. Even if we know A3 thinking was created at Toyota, how did it become so firmly entrenched in the organization’s culture? Retired Toyota leader Mr. Isao Yoshino spearheaded a special program that made A3s Toyota’s foremost means of problem-solving. Read more.

In the late 1970s, Toyota decided to invest in cultivating the managerial capabilities of its mid-level managers. Masao Nemoto, the same influential executive who led Toyota’s successful Deming Prize initiative in 1965, led a development program especially for non-production gemba managers called the “Kanri Nouryoku Program” – “Kan-Pro” for short. Nemoto chose to structure this critical management development initiative around the A3 process .

The A3 is well established now in the lean community. As a process, as a tool, as a way of thinking, managing and developing others. The question often comes up of where did it come from and how did it become a common practice. The basic answer is that it dispersed mainly from Toyota. But how did it become so prevalent in Toyota? And how did it evolve from its humble beginnings as a tool to tell a PDCA quality improvement story on an A3-sized sheet of paper, as it had been commonly used by many Japanese companies since the 1960s?

What had started as a simple tool to tell PDCA stories grew at Toyota into something more: the A3 process came to embody the company’s way of managing in an extraordinarily profound sense. How did this happen?

My first “kacho” (manager) at Toyota (in Japan starting in 1983), Mr. Isao Yoshino, was a member of Nemoto’s four-man team that created and delivered the “Kan-Pro” manager-development initiative that directly answers that question. The program has been unknown outside Toyota … until now.

-John Shook

Interview with Mr. Isao Yoshino

Q: what was the purpose of the kanri nouryoku program.

A: The main purpose was to nurture “Management Capabilities” of employees who were at manager (kacho) level and above. There were four rudimental capabilities for managers:

- Planning capability, judging capability

- Broad knowledge, experiences and perspectives

- Driving force to get job done, leadership, kaizen capability

- Presentation capability, persuasion capability, negotiation capability

Mr. Nemoto decided to take actions in reinvigorate managers (especially administrative) and help heighten awareness of their role. Mr. Isao Yoshino

Q: Why did Toyota decide it needed this program?

A: After introducing Total Quality Control (TQC) in 1961 and receiving the Deming Prize in 1965, TQC-based perspective had taken root widely across the company. In the late ‘70s, Mr. Nemoto (one of the main people behind launching TQC) noticed that management capabilities and TQC awareness was decreasing among managers, particularly within the non-manufacturing gemba or office divisions. Mr. Nemoto decided to take actions to reinvigorate the managers (especially administrative) and help heighten awareness of their role. And so, in 1978, he formed a task force that promoted a two-year program (the Kanri Nouryoku Program) for two thousand managers from all over the company. I was one of the four staff members on the task force in Toyota City.

Q: What sort of tools and activities did the Kanri Nouryoku employ?

A: All the managers went through “a presentation session” twice per year (June and December). The officers in charge of each department attended to have a Question and Answer session with the managers. Officers tried to focus on the problems each manager was facing as well as the effort and process needed to solve the problems. Officers focused more on “What is the major cause of the problem?”, rather than “Who made those mistakes?” This problem-focused attitude (as opposed to the who-made-the-mistake attitude) of the officers encouraged managers to share their problems rather than hide them.

The key to giving the presentations was that they had to be done using an A3. The managers learned how to select what information/data was needed and what was not needed, since an A3 has only limited space. This helped them acquire the seiri and seiton functions of the 5S concept as applied to knowledge work . A3 was also a great tool for officers. They could easily see, at a glance, all the key points that the presenter wanted to convey. As it is just one single document, you can quickly see from the left top corner to the right bottom of an A3 and grasp the key things the writer wants to communicate. This is something that you cannot get from a written document or PowerPoint presentation.

Q: What was your personal experience with the program?

A: First, I was fortunate to get acquainted with many admirable managers, who inspired me in many ways. I also learned how to express myself more effectively by studying A3 documents from two thousand managers. Strikingly, I discovered that managers whose A3s were excellent were also excellent managers at work.

Strikingly, I discovered that managers whose A3s were excellent were also excellent managers at work. Mr. Isao Yoshino

Nemoto-san highly praised managers who took a risk to report their mistakes (not success stories) on A3s with a hope of finding a solution. Nemoto valued their sincere and proactive attitudes. “Nemoto Lectures” were held for managers three or four times a year. Mr. Nemoto went through every single impression memo from the audience as feedback for his next speech.

Mr. Nemoto also appreciated the efforts by managers who tried to nurture excellent subordinates. This created a new company-wide notion that “developing your subordinates is a virtue.” It was amazing to see managers in their 40s and 50s willing to give 100 percent of their energy to work on hoshin kanri and A3 reporting, because they were convinced the program was practical and useful and worth using to bring themselves up to a higher level. Seeing all this happen at work truly helped me grow professionally.

Q: What was the effect of the program on Toyota?

A: Well for one, every mid-level manager who was involved in this program over the two years came to clearly understand their roles and responsibilities and also learned the importance of the hoshin kanri system. People at Toyota don’t hesitate to report bad news, which has been Toyota’s heritage since day one. The Kanri Nouryoku program has further reinforced this tradition because of its praise toward managers and others who were honest about their mistakes. And after the program was implemented to the back-office managers, the level of their awareness of their role rose up to the same level of that of manufacturing-related managers, which significantly strengthened the management foundation.

Everybody became familiar with using the A3 process when documented communication was needed – A3 thinking eventually became an essential part of Toyota’s culture. People learned how to distinguish what is important from what is not.

Managing to Learn

An Introduction to A3 Leadership and Problem-Solving.

Written by:

About Isao Yoshino

Isao Yoshino is a Lecturer at Nagoya Gakuin University of Japan. Prior to joining academia, he spent 40 years at Toyota working in a number of managerial roles in a variety of departments. Most notably, he was one of the main driving forces behind Toyota’s little-known Kanri Nouryoku program, a development activity for knowledge-work managers that would instill the A3 as the go-to problem-solving process at Toyota.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Revolutionizing Logistics: DHL eCommerce’s Journey Applying Lean Thinking to Automation

Podcast by Matthew Savas

Transforming Corporate Culture: Bestbath’s Approach to Scaling Problem-Solving Capability

Teaching Lean Thinking to Kids: A Conversation with Alan Goodman

Podcast by Alan Goodman and Matthew Savas

Related books

Daily Management to Execute Strategy: Solving problems and developing people every day

by Robson Gouveia and José R. Ferro, PhD

A3 Getting Started Guide

by Lean Enterprise Institute

Related events

January 24, 2025 | Coach-Led Online

Online – On-Demand, Self-Paced

Problem Framing Skills

Explore topics.

Stay up to date with the latest events, subscribe today.

Privacy overview.

- Project management

How to use Toyota’s legendary A3 problem-solving technique

Georgina Guthrie

February 21, 2020

If you came home one day and found your kitchen taps on full-blast and your house full of water, what’s the first thing you’d do? Grab a bucket and start scooping — or turn off the tap?

When it comes to problem-solving, many of us take a rushed, reactionary approach rather than fixing the issue at the source. So in other words, we see the water, panic, and start scooping. If this sounds like something you’ve done recently, then don’t feel too bad: when the pressure’s high, we often jump towards the quickest fix, as opposed to the most effective one.

This is where the A3 technique comes in. It’s a problem-solving approach designed to efficiently address the root cause of issues.

What is the A3 technique?

The A3 technique is a structured way to solve problems. It’s part of the Lean methodology developed by Toyota back in the mid-’40s. This doesn’t mean you need to implement a Lean way of working to take advantage of this process — it can work as a standalone exercise.

Granted, A3 isn’t an inspiring name, but the story of its origins is actually pretty interesting. Rumour has it that Taiichi Ohno, inventor of the Toyota Production System, refused to read past the first page of any report. In response, his team created A3 to address and summarize problem-solving on one side of A3-sized paper. The A3 technique played a huge part in Toyota’s success and all kinds of industries have since adopted it. Here’s how to get started.

How to solve a problem with A3

The first thing to remember is this: A3 is collaborative and relies on good communication. It’s not something you should do by yourself.

There are three main roles involved:

- Owner (that’s you or someone under your charge)

As you’ve probably guessed, these aren’t roles that already exist in your company; you must create them for the purpose of this process. Here’s what they mean.

The owner is responsible for leading the exercise. They are the lynchpin between the two other roles, fostering good communication and keeping documents up to date. It’s tempting to think of the owner as the head of this trio, but that’s not true: everyone is equal here.

The mentor is someone with solid problem-solving experience. Their job is to coach the owner and steer them toward finding a solution; it’s not their job to find the answers themselves.

And finally, there are the responders . This is someone (or a group of people) who has a vested interest in the outcome of the A3 project. Responders might include the client, stakeholders, or managers. A potential problem here is gaining access to them: if you work somewhere with a strict hierarchy — and you’re somewhere near the bottom of that structure — you may face challenges. There’s no easy way around this. Essentially, you need your organization to support this way of working and make it easy for you to access those at the top if needed.

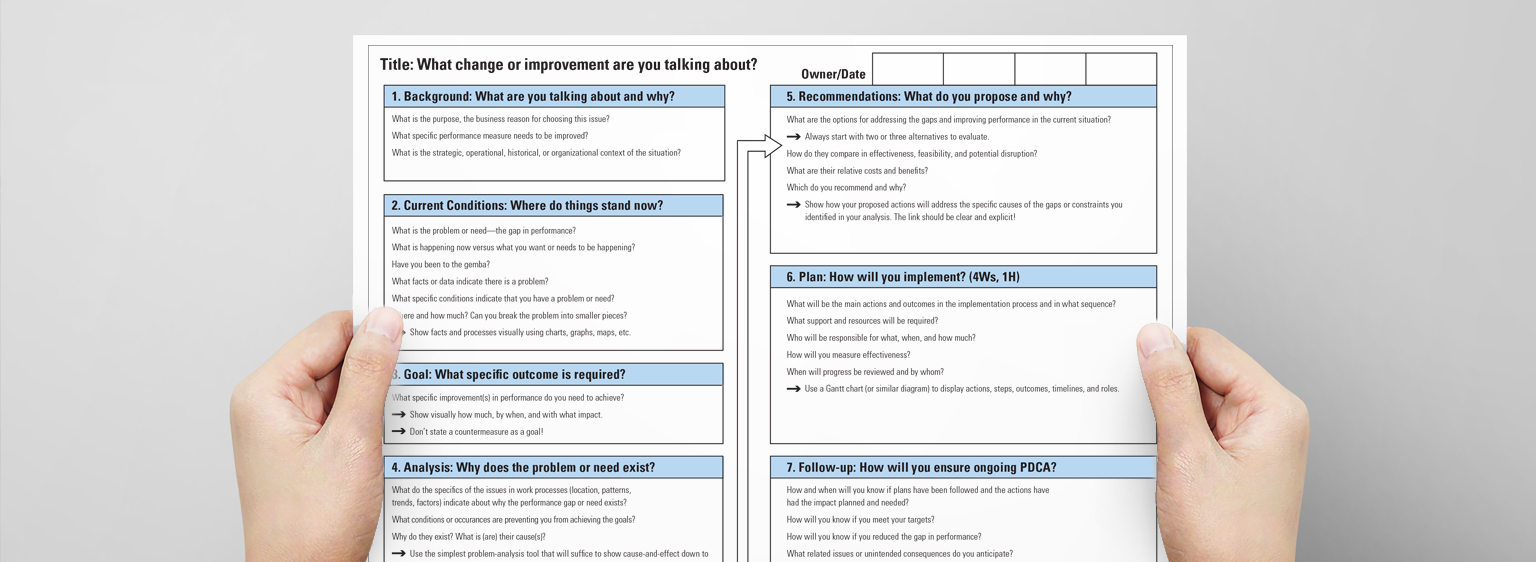

How to create an A3 report

True to its origins, the A3 report is a one-page document. It typically contains 5-7 sections that systematically lead you towards a solution. These are the most commonly used steps but feel free to modify them.

- Background: Explain your project in a few sentences, including its context.

- Problem statement: Explain the current problem. You can use process mapping to see the different tasks that surround the issue. This isn’t essential, but it will make it easier for you to locate the root cause.

- Goals: Define your desired outcome and include metrics for measuring success. You won’t know everything until you reach the end, so you may need to revisit and refine stages 1-3.

- Root cause analysis: This is a big stage of the process. You need to work out what you think the root problem is. You can use different methods to help you here, including 5 whys or a fault tree analysis .

- Countermeasures: Once you’ve worked out your root cause, you can start proposing solutions.

- Implementation: Plan how you’ll implement these solutions, including an action list with clearly defined roles and responsibilities. Project management software is useful here because it allows the team to track each other’s progress in real time .

- Follow-up: Using your metrics for success, decide whether the problem was solved. Report your results back to the team/organization. In the spirit of Lean (continuous improvement), you should go back and modify your plan if the results aren’t as expected. And if they were, you should make this process the new standard.

Problem-solving tools

A3 is an efficient, methodical way to solve problems at their source. When issues rear their head, rising stress can lead people to panic. Having a clearly designed system in place to guide you towards a solution minimizes the chances of people settling for a ‘quick fix’ or failing to act altogether.

Beyond being a guiding light in times of pressure, A3 is a great team-building exercise because it encourages individuals to work together towards a common goal — across all areas of the organization. Combine this with collaborative tools designed to help teams track progress and work together more effectively, and you’ll be unstoppable.

A comprehensive guide to creating your first SIPOC diagram

Forget batch work — continuous flow is your ticket to a more efficient way of working

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Learn with Nulab to bring your best ideas to life