Writing A Literature Review

7 common (and costly) mistakes to avoid ☠️.

By: David Phair (PhD) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2021

Crafting a high-quality literature review is critical to earning marks and developing a strong dissertation, thesis or research project. But, it’s no simple task. Here at Grad Coach, we’ve reviewed thousands of literature reviews and seen a recurring set of mistakes and issues that drag students down.

In this post, we’ll unpack 7 common literature review mistakes , so that you can avoid these pitfalls and submit a literature review that impresses.

Overview: 7 Literature Review Killers

- Over-reliance on low-quality sources

- A lack of landmark/seminal literature

- A lack of current literature

- Description instead of integration and synthesis

- Irrelevant or unfocused content

- Poor chapter structure and layout

- Plagiarism and poor referencing

Mistake #1: Over-reliance on low-quality sources

One of the most common issues we see in literature reviews is an over-reliance on low-quality sources . This includes a broad collection of non-academic sources like blog posts, opinion pieces, publications by advocacy groups and daily news articles.

Of course, just because a piece of content takes the form of a blog post doesn’t automatically mean it is low-quality . However, it’s (generally) unlikely to be as academically sound (i.e., well-researched, objective and scientific) as a journal article, so you need to be a lot more sceptical when considering this content and make sure that it has a strong, well-reasoned foundation. As a rule of thumb, your literature review shouldn’t rely heavily on these types of content – they should be used sparingly.

Ideally, your literature review should be built on a strong base of journal articles , ideally from well-recognised, peer-reviewed journals with a high H index . You can also draw on books written by well-established subject matter experts. When considering books, try to focus on those that are published by academic publishers , for example, Cambridge University Press, Oxford University Press and Routledge. You can also draw on government websites, provided they have a strong reputation for objectivity and data quality. As with any other source, be wary of any government website that seems to be pushing an agenda.

Source: UCCS

As I mentioned, this doesn’t mean that your literature review can’t include the occasional blog post or news article. These types of content have their place , especially when setting the context for your study. For example, you may want to cite a collection of newspaper articles to demonstrate the emergence of a recent trend. However, your core arguments and theoretical foundations shouldn’t rely on these. Build your foundation on credible academic literature to ensure that your study stands on the proverbial shoulders of giants.

Mistake #2: A lack of landmark/seminal literature

Another issue we see in weaker literature reviews is an absence of landmark literature for the research topic . Landmark literature (sometimes also referred to as seminal or pivotal work) refers to the articles that initially presented an idea of great importance or influence within a particular discipline. In other words, the articles that put the specific area of research “on the map”, so to speak.

The reason for the absence of landmark literature in poor literature reviews is most commonly that either the student isn’t aware of the literature (because they haven’t sufficiently immersed themselves in the existing research), or that they feel that they should only present the most up to date studies. Whatever the cause, it’s a problem, as a good literature review should always acknowledge the seminal writing in the field.

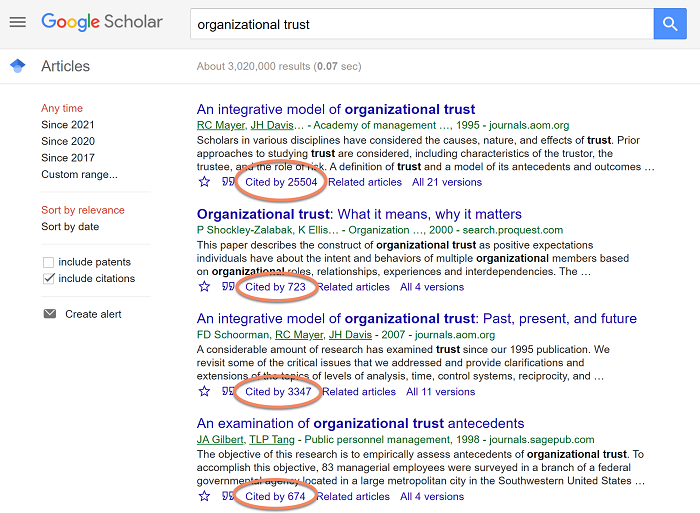

But, how do you find landmark literature?

Well, you can usually spot these by searching for the topic in Google Scholar and identifying the handful of articles with high citation counts. They’ll also be the studies most commonly cited in textbooks and, of course, Wikipedia (but please don’t use Wikipedia as a source!).

So, when you’re piecing your literature review together, remember to pay homage to the classics , even if only briefly. Seminal works are the theoretical foundation of a strong literature review.

Mistake #3: A lack of current literature

As I mentioned, it’s incredibly important to acknowledge the landmark studies and research in your literature review. However, a strong literature review should also incorporate the current literature . It should, ideally, compare and contrast the “classics” with the more up to date research, and briefly comment on the evolution.

Of course, you don’t want to burn precious word count providing an in-depth history lesson regarding the evolution of the topic (unless that’s one of your research aims, of course), but you should at least acknowledge any key differences between the old and the new.

But, how do you find current literature?

To find current literature in your research area, you can once again use Google Scholar by simply selecting the “Since…” link on the left-hand side. Depending on your area of study, recent may mean the last year or two, or a fair deal longer.

So, as you develop your catalogue of literature, remember to incorporate both the classics and the more up to date research. By doing this, you’ll achieve a comprehensive literature base that is both well-rooted in tried and tested theory and current.

Mistake #4: Description instead of integration and synthesis

This one is a big one. And, unfortunately, it’s a very common one. In fact, it’s probably the most common issue we encounter in literature reviews.

All too often, students think that a literature review is simply a summary of what each researcher has said. A lengthy, detailed “he said, she said”. This is incorrect . A good literature review needs to go beyond just describing all the relevant literature. It needs to integrate the existing research to show how it all fits together.

A good literature review should also highlight what areas don’t fit together , and which pieces are missing . In other words, what do researchers disagree on and why might that be. It’s seldom the case that everyone agrees on everything because the “truth” is typically very nuanced and intricate in reality. A strong literature review is a balanced one , with a mix of different perspectives and findings that give the reader a clear view of the current state of knowledge.

A good analogy is that of a jigsaw puzzle. The various findings and arguments from each piece of literature form the individual puzzle pieces, and you then put these together to develop a picture of the current state of knowledge . Importantly, that puzzle will in all likelihood have pieces that don’t fit well together, and pieces that are missing. It’s seldom a pretty puzzle!

By the end of this process of critical review and synthesis of the existing literature , it should be clear what’s missing – in other words, the gaps that exist in the current research . These gaps then form the foundation for your proposed study. In other words, your study will attempt to contribute a missing puzzle piece (or get two pieces to fit together).

So, when you’re crafting your literature review chapter, remember that this chapter needs to go well beyond a basic description of the existing research – it needs to synthesise it (bring it all together) and form the foundation for your study.

Mistake #5: Irrelevant or unfocused content

Another common mistake we see in literature review chapters is quite simply the inclusion of irrelevant content . Some chapters can waffle on for pages and pages and leave the reader thinking, “so what?”

So, how do you decide what’s relevant?

Well, to ensure you stay on-topic and focus, you need to revisit your research aims, objectives and research questions . Remember, the purpose of the literature review is to build the theoretical foundation that will help you achieve your research aims and objectives, and answer your research questions . Therefore, relevant content is the relatively narrow body of content that relates directly to those three components .

Let’s look at an example.

If your research aims to identify factors that cultivate employee loyalty and commitment, your literature review needs to focus on existing research that identifies such factors. Simple enough, right? Well, during your review process, you will invariably come across plenty of research relating to employee loyalty and commitment, including things like:

- The benefits of high employee commitment

- The different types of commitment

- The impact of commitment on corporate culture

- The links between commitment and productivity

While all of these relate to employee commitment, they’re not focused on the research aims , objectives and questions, as they’re not identifying factors that foster employee commitment. Of course, they may still be useful in helping you justify your topic, so they’ll likely have a place somewhere in your dissertation or thesis. However, for your literature review, you need to keep things focused.

So, as you work through your literature review, always circle back to your research aims, objective and research questions and use them as a litmus test for article relevance.

Need a helping hand?

Mistake #6: Poor chapter structure and layout

Even the best content can fail to earn marks when the literature review chapter is poorly structured . Unfortunately, this is a fairly common issue, resulting in disjointed, poorly-flowing arguments that are difficult for the reader (the marker…) to follow.

The most common reason that students land up with a poor structure is that they start writing their literature review chapter without a plan or structure . Of course, as we’ve discussed before, writing is a form of thinking , so you don’t need to plan out every detail before you start writing. However, you should at least have an outline structure penned down before you hit the keyboard.

So, how should you structure your literature review?

We’ve covered literature review structure in detail previously , so I won’t go into it here. However, as a quick overview, your literature review should consist of three core sections :

- The introduction section – where you outline your topic, introduce any definitions and jargon and define the scope of your literature review.

- The body section – where you sink your teeth into the existing research. This can be arranged in various ways (e.g. thematically, chronologically or methodologically).

- The conclusion section – where you present the key takeaways and highlight the research gap (or gaps), which lays the foundation for your study.

Another reason that students land up with a poor structure is that they start writing their literature chapter prematurely . In other words, they start writing before they’ve finished digesting the literature. This is a costly mistake, as it always results in extensive rewriting , which takes a lot longer than just doing it one step at a time. Again, it’s completely natural to do a little extra reading as thoughts crop up during the writing process, but you should complete your core reading before you start writing.

Long story short – don’t start writing your literature review without some sort of structural plan. This structure can (and likely will) evolve as you write, but you need some sort of outline as a starting point. Pro tip – check out our free literature review template to fast-track your structural outline.

Mistake #7: Plagiarism and poor referencing

This one is by far the most unforgivable literature review mistake, as it carries one of the heaviest penalties , while it is so easily avoidable .

All too often, we encounter literature reviews that, at first glance, look pretty good. However, a quick run through a plagiarism checker and it quickly becomes apparent that the student has failed to fully digest the literature they’ve reviewed and put it into their own words.

“But, the original author said it perfectly…”

I get it – sometimes the way an author phrased something is “just perfect” and you can’t find a better way to say it. In those (pretty rare) cases, you can use direct quotes (and a citation, of course). However, for the vast majority of your literature review, you need to put things into your own words .

The good news is that if you focus on integrating and synthesising the literature (as I mentioned in point 3), you shouldn’t run into this issue too often, as you’ll naturally be writing about the relationships between studies , not just about the studies themselves. Remember, if you can’t explain something simply (in your own words), you don’t really understand it.

A related issue that we see quite often is plain old-fashioned poor referencing . This can include citation and reference formatting issues (for example, Harvard or APA style errors), or just a straight out lack of references . In academic writing, if you fail to reference a source, you are effectively claiming the work as your own, which equates to plagiarism. This might seem harmless, but plagiarism is a serious form of academic misconduct and could cost you a lot more than just a few marks.

So, when you’re writing up your literature review, remember that you need to digest the content and put everything into your own words. You also need to reference the sources of any and all ideas, theories, frameworks and models you draw on.

Recap: 7 Literature Review Mistakes

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this post. Let’s quickly recap on the 7 most common literature review mistakes.

Now that you’re aware of these common mistakes, be sure to also check out our literature review walkthrough video , where to dissect an actual literature review chapter . This will give you a clear picture of what a high-quality literature review looks like and hopefully provide some inspiration for your own.

If you have any questions about these literature review mistakes, leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to answer. If you’re interested in private coaching, book an initial consultation with a friendly coach to discuss how we can move you forward.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

10 Comments

Dear GradCoach,

Thank you for making our uni student lives better. Could you kindly do a video on how to use your literature review excel template? I am sure a lot of students would appreciate that.

Thank you so much for this inlightment concerning the mistakes that should be avoided while writing a literature review chapter. It is concise and precise. You have mentioned that this chapter include three main parts; introduction, body, and conclusion. Is the theoritical frameworke considered a part of the literature review chapter, or it should be written in a seperate chapter? If it is included in the literature review, should it take place at the beginning, the middle or at the end of the chapter? Thank you one again for “unpacking” things for us.

Hi I would enjoy the video on lit review. You mentioned cataloging references, I would like the template for excel. Would you please sent me this template.

on the plagiarism and referencing what is the correct way to cite the words said by the author . What are the different methods you can use

its clear, precise and understandable many thanks affectionately yours’ Godfrey

Thanks for this wonderful resource! I am final year student and will be commencing my dissertation work soon. This course has significantly improved my understanding of dissertation and has greater value in terms of its practical applicability compared to other literature works and articles out there on the internet. I will advice my colleague students more especially first time thesis writers to make good use of this course. It’s explained in simple, plain grammar and you will greatly appreciate it.

Thanks. A lot. This was excellent. I really enjoyed it. Again thank you.

The information in this article is very useful for students and very interesting I really like your article thanks for sharing this post!

Thank you for putting more knowledge in us. Thank you for using simple you’re bless.

This article is really useful. Thanks a lot for sharing this knowledge. Please continue the journey of sharing and facilitating the young researchers.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- Reply to Danette - Allessaysexpert - […] Jansen, D. (2021, June). Writing a literature review: 7 common (and costly) mistakes to avoid. https://gradcoach.com/literature-review-mistakes/ […]

- Reply to Danette - Academia Essays - […] Jansen, D. (2021, June). Writing a literature review: 7 common (and costly) mistakes to avoid. https://gradcoach.com/literature-review-mistakes/ […]

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

5 Literature Review Dos and Don’ts: A Guide for All Students

by Antony W

December 6, 2022

In this guide, you’ll learn about the most common literature reviews dos and don’ts to stay on the right track as you work on the assignment.

Up until now, we’ve written guides on

- How to write comprehensive literature reviews

- The role literature reviews play in research writing

- The elements of a literature review

Plus, there’s a lot more.

With the help of these posts, you can come up with the best study of already existing literature, which is singlehandedly significant in writing a research paper or dissertation project.

Problem is:

Not all students get their literature review right 100% of the time, and that’s because they make some LR mistakes that they should avoid in the first place.

So in this guide, you’ll learn about the dos and don’ts of literature review, so you can write what makes sense and earn the A-grade level marks for the entire paper.

5 Literature Review Dos and Don’ts

As a college or university student, you wish is to score the best grade for your literature review, either as a standalone assignment or as a part of a research paper or dissertation.

So here are the writing rules to observe to get that A for the assignment:

1. Write Relevant and Focused Content

One of the reasons why students fail to score top marks for their literature review chapters because they fill the assignment with irrelevant content.

If after reading your review the reader asks the “so what?” question, there’s a high chance your work isn’t as focused as it should be in the first place.

Make sure you stay on topic from the very beginning.

The right approach to ensure your content is on point is to take another closer look at your research question, aims, and objectives, and then re-evaluate your theoretical framework to see if it related to these components.

Reevaluation may demand extra time, but spending more time on the assignment is the only way to make sure your work actually focuses on existing research that addresses the topic under investigation. Often, it helps to circle back to your research question, aims, and objectives to ascertain that your study of existing literature is on point.

2. Do Make Sure Your Literature is Current

Many students don’t feature current literature in their work, and that’s just a wrong way to get the work done by modern standards. While it’s significant to acknowledge landmark research and studies in your writing, your work should also include current literature.

Including current literature in your work gives you the opportunity to compare and contrast old and recent research data and share your thoughts on the evolution.

Finding and incorporating current literature in your work doesn’t have to be difficult at all.

- Google to Google Scholar and search your topic.

- Select one of the “Since…” links on the top left to filter the result based on a given date.

Keep in mind that what’s current won’t mean the same thing to all students. In fact, depending on your area of study, you might filter the results to show you research literature that are a year older, two years older, or more.

There’s a reward to doing this.

More often than not, a mix of class and recent research enables you to write a more comprehensive literature review.

3. Don’t Give Descriptions, Integrate and Synthesize Instead

Giving descriptions is one of the biggest problems in literature review writing. Quite too often, students focus on outlining what researchers said and end up making their literature review less comprehensive.

You need to do a lot more than just describing.

Your literature review needs to feature an integration of multiple existing research and show exactly how all the pieces fit together.

Don’t hesitate to go the extra mile to mention the missing pieces and the areas that simply don’t fit together, not to mention give reasons why you believe researchers have conflicting opinions on those areas.

Identifying conflicts in existing literature is a great way to find gaps that current and future research should address. By including a mix of perspectives in your work, you demonstrate that you did enough research that not only offers balanced review but also provides a clear perspective of the current knowledge on the topic.

4. Don’t Rely on Low-quality Sources

One of the most common mistakes students make is relying on low-quality sources, such as daily news articles, opinion pieces, and regular blog posts, to write literature review . In doing so, professors often end up rating their work as either incomplete or academically unsound.

Even if you think a recent news article or an interesting blog post you read recently can make a good fit for your literature review project, it most often unlikely to be as significant. So, you need to be more skeptical when it comes to picking your sources.

The most important rule here is that you refrain from using daily news articles, opinion pieces, and regular blog posts as your source of information. If you must use them, then do so only sparingly.

In fact, the right sources for reference are those that help you to build a strong theoretical framework because they’re academically sound. If anything, we can’t stress enough how important it is to consider peer-reviewed articles for your research.

You also have the liberty to explore books written by established and academically recognized authors who are experts in the area you’re investigating. And although your professor won’t mind if you draw information from government websites, you need to make sure those sites have a good reputation for being objective with what they publish.

5. Don’t Make These Stylistic and Writing Mistakes

There are stylistic and writing mistakes that you must avoid when working on a literature review. You should:

- Never use emotional phrases in your work. Your goal with this project is to present classic and current research on your research topic. Given that you’re relying on information that already exists, you don’t have the room to include subjective and emotional words in your writing.

- Avoid writing your personal opinion in the review. Literature reviews have to be objective and based on facts drawn from already exiting research around your topic.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

The do’s and don’ts of writing review articles

If you (or a global pandemic) take the bench away from the scientist, what do they do? They write reviews of course!

As many of us are now far too familiar with, crafting a review article presents a series of unique challenges. Unlike a manuscript, in which the nature of your data inherently shapes the narrative of the article, a review requires synthesizing one largely from scratch. Reviews are often initiated without a well-defined scope going in, which can often leave us feeling overwhelmed, like we’re faced with covering an entire field.

With these challenges in mind, here are a few tips and tricks to make review writing as painless as possible, for the next time you lose your pipette:

- Defining this viewpoint can be extremely helpful in limiting the scope of your literature search, preventing the overwhelming feeling of having to read every paper ever — focus your time and energy on deep-dives into those papers most important to this motivating viewpoint.

- Ask yourself: Who do you want reading your review? What could you cover that would be most helpful to them?

- This will be an iterative process — the focus of your review will likely change significantly over the writing process, as you read more papers and start organizing your thoughts.

- For each review, ask: What are their take-home messages? How can you differentiate your own from each of these?

- As a member of the field, look out for things you wish they had covered: “I wish they had a figure on this, I wish they discussed this, I wish they clarified this…”

- Are there key papers that they missed?

- Are there key papers that have been published since these reviews have been published?

- Cite other reviews to save yourself some writing! If a tangentially related topic is outside of the scope of your review, it’s commonplace to reference other reviews for the sake of brevity, and to recognize their hard work: “X is outside of the scope of this review, but is covered in-depth here [Ref]”).

- For each paper, ask: What was known before this paper, what did this paper show, and what are its limitations?

- It’s important to accept the fact that it is impossible to read, let alone discuss in-depth, hundreds and hundreds of papers.

- Depending on how each paper will fit into your article’s narrative, it may only be necessary to review specific sections or figures. [ I don’t have to read every word of every paper?! ]

- Given the unstructured nature of a non-data-driven article, this is a hugely important step in the process that will make writing infinitely less painful.

- Which key papers are you going to discuss in which sections?

- Outline subsections and transitions under each major section.

- Engage with your PI early and often in the process of crafting your outline, and try to get explicit approval of the finished product before you start writing — this can save you from a lot of painful backtracking later!

- Writing and structuring your review should be iterative as you continue to refine, read more papers, and start to actually get words down on the page

- The most helpful reviews synthesize the findings of multiple papers into a cohesive take-home message.

- Think about how specific findings relate to your overarching motivation for this article

- Think about how different papers relate to each other — do different studies align, or do they contradict each other?

- Keep in mind how people generally skim articles, by skimming the figures — reviews are no different

- Figures should be included in your structural outline

- For example, many people pull schematics from their own reviews to use directly in background slides of future presentations

- While you cannot avoid citing and discussing major, high impact papers from larger journals, consider that these have likely already been discussed in great depth by other reviews given their high visibility. Good research exists in smaller journals, and you can do your part to cast a light on this work.

- You can provide a fresh perspective by looking outside your field for analogous research, provided you can find a creative way to fit it into the scope of your review’s narrative.

Blog post written by Caleb Perez , with input from Tyler Toth, Viraat Goel , and Prerna Bhargava .

Reviews versus Perspectives- It’s important to draw the distinction between reviews and perspectives here. Although we believe that both should review the field in the context of some overarching scientific viewpoint, perspective articles allow the author much more freedom to craft a more opinionated argument and are generally more forward-thinking. If you have that freedom, definitely use it!

Belonging to a group- Of course, the extent to which you can do this may be limited, depending on how familiar you are with the field. First-year graduate students getting into a new field, for example, may not have as great of a grasp on the gaps in the field — you may have to lean on the advice of your PI and colleagues to help guide you here, especially in the early stages of the process before you start your in-depth literature search.

How to read a paper- There are many situations in which a narrower, targeted paper review is warranted. As one example, imagine a section of a review in which you are comparing different technologies for application X. In this context, you may only need to do a detailed review of the methods sections and any figures they have that benchmark their method for your particular application of interest. The rest of the paper is less relevant, so there’s no need to waste your valuable time and energy.

The Dos and Don'ts of Literature Review in Scientific Writing

The literature review stands as a critical pillar in the edifice of scientific writing, serving as the gateway to informed research by surveying and synthesizing existing knowledge. It is a nuanced art that requires precision and careful execution, demanding an understanding of both what to do and what to avoid. This article delves into the intricacies of mastering the literature review process, shedding light on the dos that enhance the effectiveness of this scholarly endeavor while elucidating the don'ts that can hinder its impact. A well-crafted literature review not only establishes the foundation of a research project but also demonstrates the researcher's ability to navigate the scholarly landscape with discernment and finesse.

The Dos of a Literature Review

A well-executed literature review is an integral part of scholarly research, providing a foundation for your study and contributing to the advancement of knowledge. To ensure the effectiveness and quality of your literature review, consider these key "dos" as you navigate the process:

1. Clearly Define Your Scope: Clearly outline the boundaries of your literature review. Define the specific topic, research question, or theme you're addressing to maintain focus.

2. Conduct Thorough Searches: Use multiple reputable databases and sources to gather a comprehensive array of relevant literature. Explore various keywords and synonyms to capture a wide range of perspectives.

3. Organize Your Review: Structure your review logically. Consider organizing it chronologically, thematically, or methodologically based on your research objectives.

4. Synthesize and Analyze: Rather than merely summarizing sources, synthesize and analyze the findings, methodologies, and key arguments. Identify trends, patterns, and gaps in the existing literature.

5. Identify Key Concepts and Theories: Highlight the fundamental concepts, theories, and models that underpin the topic. This showcases your understanding of the field's foundational knowledge.

6. Address Differing Perspectives: Address conflicting viewpoints and contradictory findings in the literature. Discussing opposing views demonstrates your critical thinking.

7. Establish a Context: Situate your study within the broader academic landscape. Show how your research fits into the existing body of knowledge and contributes to the field.

8. Evaluate Source Credibility: Assess the credibility of each source. Consider factors like author credentials, publication venue, and methodology to determine the reliability of the information.

9. Present a Balanced View: Present a balanced overview of the literature. Highlight both the strengths and limitations of each study to offer a fair assessment.

10. Create Logical Transitions: Ensure smooth transitions between different sections and sources. A well-organized flow enhances the readability and coherence of your review.

11. Address Research Gaps: Identify gaps in the existing literature that your research aims to fill. Articulate how your study addresses these gaps and contributes to the field.

12. Use Appropriate Citations: Properly cite all sources using the required citation style. Accurate citations give credit to the original authors and support the credibility of your review.

13. Provide Visual Aids: Consider incorporating tables, graphs, or diagrams to illustrate key trends or relationships in the literature. Visual aids can enhance the clarity of your review.

14. Proofread and Edit: Thoroughly review your literature review for grammatical errors, typos, and formatting issues. A polished presentation reflects your professionalism.

15. Stay Current: Keep up-to-date with the latest research even after completing your initial literature review. Emerging studies can influence the direction of your research.

Receive Free Grammar and Publishing Tips via Email

The don'ts of a literature review.

A literature review is a critical component of scholarly research, offering an overview of existing knowledge on a specific topic. While there are guidelines for what to include, it's equally important to be aware of the pitfalls to avoid. Steering clear of these common missteps can enhance the effectiveness and credibility of your literature review:

1. Don't Simply Summarize: A literature review is more than a summary of each source. Avoid turning it into a laundry list of article summaries. Instead, focus on synthesizing and analyzing the information.

2. Don't Be Unfocused: Define a clear scope and purpose for your literature review. Avoid wandering into unrelated areas or discussing irrelevant studies.

3. Don't Rely on a Single Source: A literature review requires a comprehensive approach. Relying solely on one or a few sources can lead to biased or incomplete conclusions.

4. Don't Ignore Contradictory Findings: Acknowledge conflicting findings in the literature. Ignoring opposing viewpoints weakens the credibility of your review.

5. Don't Use Outdated Sources: Outdated sources can undermine the relevance and accuracy of your literature review. Prioritize recent, credible publications.

6. Don't Overuse Direct Quotes: While quotes can support your points, overusing them clutters your review. Summarize and paraphrase to demonstrate your understanding.

7. Don't Cherry-Pick Evidence: Present a balanced view of the literature. Avoid cherry-picking studies that only support your viewpoint.

8. Don't Oversimplify Complex Topics: If the topic is intricate, avoid oversimplification. Summarize complex concepts accurately, even if they require more space.

9. Don't Neglect Methodology and Quality: Assess the methodology and quality of each source. Consider factors like sample size, research design, and methodology when evaluating credibility.

10. Don't Use Biased Language: Maintain a neutral tone. Avoid overly enthusiastic or biased language that may signal a lack of objectivity.

11. Don't Forget to Cite Properly: Properly cite all sources using the required citation style. Failing to give credit can lead to plagiarism.

12. Don't Sacrifice Clarity for Length: While comprehensive, a literature review should be concise and organized. Avoid including excessive details that detract from the main points.

13. Don't Neglect Synthesis: Connect the dots between different sources. Highlight patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

14. Don't Overwhelm with Citations: While citations are crucial, excessive citations in a short span can disrupt the flow. Balance the text with citations.

15. Don't Rush the Process: A well-constructed literature review takes time. Rushing through it can result in errors, omissions, and a lack of depth.

Impactful Literature Review

The culmination of adhering to the dos and avoiding the don'ts of a literature review results in a narrative that extends beyond the confines of a mere summary. An impactful literature review serves as a guiding beacon, illuminating the path for both the researcher and the audience. By meticulously adhering to the guidelines for effective literature review construction, researchers forge a bridge between the past and the present, anchoring their research in a comprehensive understanding of the existing landscape. Through critical analysis, synthesis, and contextualization, the literature review becomes more than a mere preamble; it becomes a testament to the researcher's prowess in navigating the complexities of scholarly discourse. This section showcases the evolution from the art of information assimilation to that of information integration, with a profound effect on the subsequent research. The literature review thus emerges as a compass, directing the researcher toward underexplored territories, guiding the formulation of research questions, and setting the stage for informed methodology and robust findings. As science thrives on cumulative knowledge, an impactful literature review not only fulfills an academic requirement but also contributes to the broader tapestry of human understanding, underscoring the significance of meticulous review construction.

Connect With Us

Dissertation Editing and Proofreading Services Discount (New for 2018)

May 3, 2017.

For March through May 2018 ONLY, our professional dissertation editing se...

Thesis Editing and Proofreading Services Discount (New for 2018)

For March through May 2018 ONLY, our thesis editing service is discounted...

Neurology includes Falcon Scientific Editing in Professional Editing Help List

March 14, 2017.

Neurology Journal now includes Falcon Scientific Editing in its Professio...

Useful Links

Academic Editing | Thesis Editing | Editing Certificate | Resources

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, an end-to-end process of writing and publishing influential literature review articles: do’s and don’ts.

Management Decision

ISSN : 0025-1747

Article publication date: 25 June 2018

Issue publication date: 23 October 2018

Literature reviews are essential tools for uncovering prevalent knowledge gaps, unifying fragmented bodies of scholarship, and taking stock of the cumulative evidence in a field of inquiry. Yet, successfully producing rigorous, coherent, thought-provoking, and practically relevant review articles represents an extremely complex and challenging endeavor. The purpose of this paper is to uncover the key requirements for expanding literature reviews’ reach within and across study domains and provide useful guidelines to prospective authors interested in generating this type of scientific output.

Design/methodology/approach

Drawing upon the authors’ own experience of producing literature reviews and a scrutiny of review papers in major management journals, the authors develop an end-to-end process of writing and publishing review articles of high potential impact.

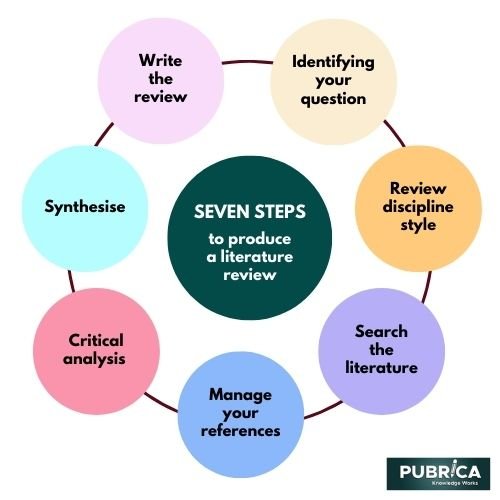

The advanced process is broken down into two phases and seven sequential steps, each of them being described in terms of key actions, required skill sets, best practices, metrics of assessment and expected outcomes.

Originality/value

By tapping into the inherent complexity of review articles and demystifying the intricacies associated with pursuing this type of scientific research, the authors seek to inspire a wealth of new influential surveys of specialized literature.

- Literature review

- Best practice guidelines

- Future research agenda

- High-impact review article

- Research synthesis

- Writing and publishing

Acknowledgements

This paper forms part of a special section Special Review Issue.

Bodolica, V. and Spraggon, M. (2018), "An end-to-end process of writing and publishing influential literature review articles: Do’s and don’ts", Management Decision , Vol. 56 No. 11, pp. 2472-2486. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2018-0253

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2018, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Do’s and Don’ts in writing a scientific literature review for health care research

Advancement in block chain technology for data sharing in biomedical research – the key factors in writing a literature review

Cancer research writing: how to plan and write a research proposal

- Healthcare research is a rapidly growing hey field necessitating the need to do an adequate and comprehensive review of existing literature on the subject.

- Clinical literature review services are in the know-how of writing an effective literature review article.

Purpose of literature review in healthcare research

The whole purpose of research is to increase the collective understanding on the topic and contribute productively.To achieve this, one must begin by understanding the context of the ‘conversation’. And this important task is done by writing a literature review article.

The number of publications, research, and journalsare increasing by the day with an increasing need for dedicated medical writing or literature review services with domain-related expertise. Proportionally the number of rejections is also on the rise. Literature review writing is the first step towards any research and making a clear case for the research study at hand is achieved by a well-done review. Clinical literature review services are providing immense support to busy clinicians and researchers on how to write a literature review. The purpose of a proper literature review can be summarized as below: –

- Literature review help explore previous research conducted in the field of interest, the limitations and conflict areas identified and the need for further research. This justifies the relevance and originality of the research work.

- It also helps one in understanding and formulating one’s area of research in a better manner and justifies the methodology used.

- Literature review article helps connect the statistical findings of the research with prior research statistics.

- It also conveys that the researcher is serious and dedicated about the research and intends to complete the project.

- Literature review writing help is needed in preventing duplication of research and avoiding redundant fields and is needed for good quality research paper.

- Literature review is the preliminary step in any dissertation as part of an academic requirement. How to write a literature review is also an important part of the curriculum.

In short, literature review writing is done to place our research within the context of the topic-related existing research and justifies the need for proposed research.

Context of literature review writing

There are various circumstances under which one must do a literature review.

- Introduction to a primary research topic – This sets the context for the research article or dissertation by analysing previously published literature and clearly defining the place of the current research and its contribution to the advancement in the understanding of the topic in question.

- Systematic review –It is related to meta-analysis and provide a quantitative or less often qualitative statistic summarizing several papers.

- Secondary data analysis projects- It is a research project on its own and begins with a clear research question. The project aims at analysing available data in answering the question.

Do’s and don’ts in literature review

Do’s .

- The research question should beclear and crisp, preferably one thatcan be analysedquantitatively.

- Picking up the right articles is an art and one should have clear inclusion and exclusion criteria to perform a relevant review.

- Citations should be recent and relevant in the current context.

- Citations should include not only those studies with clear-cut outcomes or inferences, it should also include those that are inconclusive or require further research. This is required for 360 degree understanding, avoiding bias, and defining further scope for research.

- Critical appraisal of the studies cited with an analytical review of the same is to be done.

- Adequate number of citations is often defined by the journal and that needs to be followed.

- Organise and document the data in a format that best suits and justifies the research study.

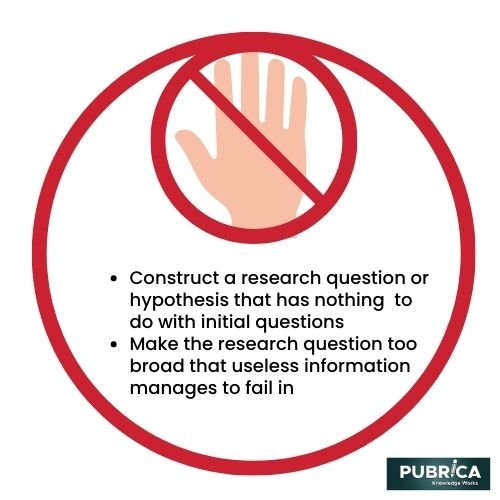

- Research question should not be ambiguous as it will result in a haphazard start to the research study.

- Deviations or inconsistency in following the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria make the findings unreliable.

- Citations that are old and outdated in the current context are to be avoided.

- Bias in citations that intentionally quote only those that are congruent in their conclusions to the current study should be avoided.

- Not weighing the studies under consideration for the quality of research result in inclusion of poor-quality literature that make the outcomes unreliable.

- Too few or too many citations fail to convey the crux in the correct proportions.

- Data organised in a haphazard manner becomes inconclusive and does not interest the reader and sends a wrong message about the quality of the study.

Basically, depending on the requirement of the topic of literature research , whether it is recent or been around for several years, whether most facts are clear or unclear, whether researchers agree or disagree on most matters and what is the outcome needed out of the literature search in context of the objective of the current study.In short, the review should be well-structured and should have some form to the flow of information.

Some broad guidelines are provided by PRISMA that gives a checklist of 27 items along with flowcharts to help in a comprehensive search.

Setting the factual context of the current research study is the first stepto participate in the ongoing ‘dialogue’ on the subject and contribute positively to that area of research. Literature review services help the busy researcher and how to write a literature review article.

- Lingard L. Joining a conversation: the problem/gap/hook heuristic. Perspect Med Educ. 2015 Oct; 4(5):252-3.

- Maggio, L. A., Sewell, J. L., &Artino, A. R., Jr (2016). The Literature Review: A Foundation for High-Quality Medical Education Research. Journal of graduate medical education, 8(3), 297–303.

- Baker, J.D. (2016), The Purpose, Process, and Methods of Writing a Literature Review. AORN Journal, 103: 265-269.

- Christine Susan Bruce (1994) Research students’ early experiences of the dissertation literature review, Studies in Higher Education, 19:2, 217-229.

- Efron, S. E., &Ravid, R. (2019). Writing the literature review: A practical guide. The Guilford Press

- Bollacker, K., Lawrence, S., and Giles, C. L. Discovering relevant scientific literature on the web. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 15(2), 42–47, 2000

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009 Jul 21; 6(7):e1000097.

pubrica-academy

Related posts.

Making Sense of Effect Size in Meta-Analysis based for Medical Research

Copy of PUB-Evidence-based analyses to look at cost-effectiveness, cost-benefit information & clinical data from RT-Device Manufacturers

The Role of Packaging Design In Drug Development

PUB - Selecting material for drug development

Selecting materials for medical device industry

Comments are closed.

Write Abstracts, Literature Reviews, and Annotated Bibliographies: Literature Reviews

- Abstract Guides & Examples

- Literature Reviews

- Annotated Bibliographies & Examples

- Student Research

What is a Literature Review?

According to the Writing Center at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill , "A literature review discusses published information in a particular subject area, and sometimes information in a particular subject area within a certain time period."

Although a literature review may summarize research on a given topic, it generally synthesizes and summarizes a subject. The purpose of a literature review therefore is to present summaries and analysis of current research not contribute new ideas on the topic (making it different from a research paper).

Search for Literature Reviews

How to Write a Literature Review

- Learn How to Write a Review of Literature (The University of Wisconsin)

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It (University of Totonto)

- Write a Literature Review (UC Santa Cruz)

- Teaching the Literature Review Details strategies on how to teach students about literature reviews and how to create their own reviews.

Dos and Don'ts of a Literature Review

Make a clear statement of the research problem. Keep it in discussion style. Give a critical assessment of your chosen literature topic, try to state the weaknesses and gaps in previous studies, try to raise questions and give suggestions for improvement.

List your ideas or theories in an unrepeated and sensible sequence. Write a complete bibliography that provides the resources from where you had collected the data in this literature review.

Use unfamiliar technical terms or too many abbreviations. Use passive voice in your text. Repeat same ideas in your text. Include any ideas that you read in the article without citing them (author's name, publication date) as a reference source. Include punctuation and grammatical errors.

- << Previous: Abstract Guides & Examples

- Next: Annotated Bibliographies & Examples >>

- Last Updated: Feb 15, 2024 4:00 PM

- URL: https://library.geneseo.edu/abstracts

Fraser Hall Library | SUNY Geneseo

Fraser Hall 203

Milne Building Renovation Updates

Connect With Us!

Geneseo Authors Hall preserves over 90 years of scholarly works.

KnightScholar Services facilitates creation of works by the SUNY Geneseo community.

IDS Project is a resource-sharing cooperative.

CIT HelpDesk

Writing learning center (wlc).

Fraser Hall 208

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

Literature: A Research Guide for Graduate Students

Research dos & don'ts.

- Get Started

- Find a Database

DON'T reinvent the wheel

Many scholars have spent their entire careers in your field, watching its developments in print and in person. Learn from them! The library is full of specialized guides, companions, encyclopedias, dictionaries, bibliographies, histories and other "reference" sources that will help orient you to a new area of research. Similarly, every works cited list can be a gold mine of useful readings.

- Techniques for finding where a particular publication is cited (reverse footnote-mining) [Harvard Library FAQ]

- Top resources and search tips for locating scholarly companions and guides [general topic guide for literary research]

- The literature section of the Loker Reading Room reference collection [HOLLIS browse]

- James Harner's Literary Research Guide: an Annotated Listing of Reference Sources in English Literary Studies [HOLLIS record with ONLINE ACCESS]

DO get to know your field

Know Your Field , a module from Unabridged On Demand, offers tips, thought prompts, and links to resources for quickly learning about and staying current with an area of scholarly study.

DON'T treat every search box like Google or ChatGPT

Break free of the search habits that Google and generative AI have taught you! Learn to pay attention to how a search system operates and what is in it, and to adjust your search inputs accordingly.

Google and generative AI interfaces train you to type in your question as you would say it to another person. They give you the illusion of a search box that can read your thoughts and that access the entire internet. That's not what's actually happening, of course! Google is giving you the results others have clicked on most while generative AI is giving you the output that is most probable based on your input. Other search systems, like the library catalog, might be matching your search inputs to highly structured, human-curated data. They give the best results when you select specific keywords and make use of the database's specialized search tools.

Learn more about searching:

- Database Search Tips from MIT: a great, concise introduction to Booleans, keywords v. subjects, and search fields

- Improve Your Search , a module from our library research intensive, Unabridged On Demand

Search technique handouts

- "Search Smarter" Bookmark Simple steps to improve your searching, plus a quick guide to the search commands HOLLIS uses

- Decoding a database A two-page guide to the most effective ways to quickly familiarize yourself with a new system.

- Optimize Your Search A 3-column review of the basic search-strategy differences between Google and systems like JSTOR or HOLLIS.

DO adjust your language

Searching often means thinking in someone else's language, whether it's the librarians who created HOLLIS's subject vocabularies, or the scholars whose works you want to find in JSTOR, or the people of another era whose ideas you're trying to find in historical newspapers. The Search Vocabulary page on the general topic guide for literary studies is a great place to start for subject vocabularies.

DON'T search in just one place

Judicious triangulation is the key to success. No search has everything. There's always one more site you could search. Strike a balance by always searching at least 3-4 ways.

DO SEARCH A VARIETY OF RESOURCES:

- Your library catalog , HOLLIS

- A subject-specific scholarly index , such as the MLA International Bibliography , LION (Literature Online) , or the IMB (International Medieval Bibliography)

- A full-text collection of scholarship, such as JSTOR or ProjectMuse

- One of Google's full-text searches, Google Scholar or Google Books

DO look beyond the library's collections

The library purchases and licenses materials for your use. There's plenty of other material that's freely available or that you would need to travel to see---please let me help you find it!

- << Previous: Find a Database

Except where otherwise noted, this work is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which allows anyone to share and adapt our material as long as proper attribution is given. For details and exceptions, see the Harvard Library Copyright Policy ©2021 Presidents and Fellows of Harvard College.

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

Do’s and Don’ts for Research Writing

In the thick of doing research, it’s easy to forget about the ultimate goal of writing and publishing. Thankfully, about once a month, the Princeton University Laser Sensing Lab holds what we call a “literature review”: Everyone brings in papers they’ve come across for their own research, and shares techniques that could be useful for the group at large.

At our last meeting, someone changed things up. Instead of bringing in a paper that contained interesting ideas, he brought one that he declared “the worst paper I’ve ever read”.

We all had a good laugh as the paper was passed around. He was right. The paper had numerous grammatical mistakes and many passages were indecipherable. But my adviser suggested that we not take it lightly. After all, this paper had somehow been published (though if he had any say in it, he would have it retracted). It served as a good example of what not to do—especially as the writing season falls upon us (hello to senior theses and final papers!).

As you write, here are other do’s and dont’s to keep in mind:

1. Don’t blow off grammar. Grammar mistakes look very unprofessional and immediately sink your standing in the eyes of your readers. The most common example? Its vs. it’s. Not only is this typo rampant in papers, but also in emails and online articles. Other examples I’ve come across: “development activities are currently been carried out ”, “in motion along our line of site ”… the list goes on. Don’t worry—we all make these typos when writing, and they’re easy to miss. I often don’t find my mistakes until I ask someone else to read over my work. But correcting grammar is a very simple fix, and can go a long way to help clean up your writing.

2. Don’t make excuses for poor writing. “Scientists aren’t known for being good writers, so it’s ok if my writing isn’t good either.” “This paper doesn’t count for much anyway, so it’s ok if it doesn’t make sense.” Yes, it’s tempting. But you don’t want to get into a habit of poor writing. And would you really want to be the TA or professor on the other end, reading a nonsensical paper?

3. Write something you would want to read. It sounds obvious, but it’s one of the most often ignored adages. Do you really need all that jargon up front? Are you giving your target audience, whether it’s fellow students or scientists, enough information to understand your writing? After you write your piece, the last thing you might feel like doing is reading it over again. But if you’re really aiming for a good paper, you should finish your draft with enough time—at least a day if possible— before re-reading, to make sure your logical progressions are natural. And another round of proofreading is a great way to catch those rogue typos!

4. Have others check over your writing. If you can’t bring yourself to read your own writing, or can’t distance yourself enough to think about what may or may not make sense, have someone proofread for you. Even if you’ve read over your own paper, you might not be able to catch confusing or illogical wording — after all, you’re the one who wrote it. But having another person’s eyes on your paper can provide an important sanity check. The Writing Center is great for this, but if you want more tailored feedback, asking for help from a graduate student in your lab is not a bad idea, either!

And finally, do your research! Take note of papers you’ve found helpful in your literature review. What kind of language do they use? Is there anything confusing they’ve done that you think you can do better? Do try and actually read some of the papers you’re citing. After all, reading good writing will make you a better writer yourself.

–Stacey Huang, Engineering Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Writing a review—the do’s and don’ts

Proceedings b senior editor dr maurine neiman discusses the value of peer review and highlights the different elements to consider when writing a review report..

Preprint and Senior Editor of Proceedings of the Royal Society B , Dr Maurine Neiman , from the University of Iowa, shared her thoughts on peer review and what makes a good review in scientific scholarly publishing.

Why is peer review important for scientists and scientific research?

Peer review is important because scientific peers have the expertise and contextual knowledge that is needed to rigorously and fairly evaluate the extent to which a new scientific paper makes a valid and useful (i.e., publishable) scientific contribution. The process isn’t perfect: humans can never be truly objective, for example, and not all reviewers provide useful or fair reviews. This is where my role as an editor can be especially important: it’s my responsibility to select high-quality reviewers, decide when particular reviews are especially useful or should be taken with a grain of salt, and provide my own independent assessment of the utility and quality of the paper.

As an Editor, what do you think makes a good review of a scientific paper?

There are multiple elements of a high-quality peer review. First , the review should be reasonably objective. Second , the review should be thorough, with the caveat that it can be difficult to find individual reviewers that can rigorously evaluate interdisciplinary studies and papers that feature multiple methodology types (e.g., theory and empirical data). Third , the review should provide a combination of appropriately positive and critical components, and constructive suggestions accompanying the critiques. With respect to the importance of positivity, the editor needs the expertise of the peer reviewers to evaluate the extent to which the paper has strengths as well as weaknesses. Fourth , the review should acknowledge components of the manuscript that the reviewer might not be able to objectively or rigorously evaluate. Finally , the review should provide a realistic perspective on what constitutes a useful contribution to scientific literature, in general, and with respect to the focal journal.

What should reviewers avoid when writing their reviews?

As I mentioned above, reviewers should avoid presenting criticism in the absence of constructive suggestions. As an author and as an editor, it can be very difficult to know how to respond to criticism in the absence of specific suggestions for improvement. As a related point, I think that reviewers should take some care to ensure that their review will come across to the authors as respectful and not overly harsh. No one benefits from an antagonistic review process.

What advice do you have for early career researchers starting out in peer review?

I think that early-career researchers should make an effort to engage in peer review early and often because reviewing is the best way to learn how the peer-review process works and provides valuable insight in how best to craft a scientific manuscript. The best way for junior researchers to start reviewing is often to team up with a graduate or postdoc advisor or other senior mentors. This type of co-review provides a direct but supervised means of gaining experience with review and will help make the junior researcher more visible to their peers, leading to more review invitations in the future. More and more journals are explicitly encouraging peer reviewers to involve students in this way, which I think is a really positive development. I do think that scientists who are new to the peer review process, perhaps as a function of graduate seminar courses focused on ‘paper bashing’, often believe that their main role as a reviewer is to be extremely critical. While this type of review can be useful, new reviewers should remember the importance of speaking to the positive elements of a paper and providing constructive suggestions alongside their critiques.

What are your thoughts on transparency in peer review?

Transparency in peer review is such a complicated issue. While I believe that transparency in science is generally a positive (and important) step forward, I think that our human challenges with objectivity mean that it is important to maintain opacity with respect to the identities of the people reviewing the papers. In other words, anonymous peer review (and, perhaps, in many/most cases, a double-blind peer review process) seems important to implement as a mechanism to maximise objectivity and minimise the negative consequences of implicit and explicit bias. This perspective doesn’t exclude the possibility that the anonymised peer reviews are published alongside the papers (an idea that I like, at least in principle), or that peer reviewers can choose to make their identities public.

If you are interested in reviewing for Proceedings B or any other Royal Society journal, find out about the benefits of reviewing for our journals on our website .

Image credit: Dr Maurine Neiman, University of Iowa

Shalene Singh-Shepherd

Senior Publishing Editor, Proceedings B

Related blogs

Buchi Okereafor

In publishing

AI and the future of scholarly publishing (part 1)

The focus for this year's Peer Review Week is 'Peer Review and the Future of Publishing'. We speak…

AI and the future of scholarly publishing (part 2)

Matt Hodgkinson, Research Integrity Manager at the UK Research Integrity Office, gives us an…

Callum Shoosmith

The future of peer review in the 17th Century

For Peer Review Week 2023 we explore the Royal Society’s collection of centuries-old referee…

Email updates

We promote excellence in science so that, together, we can benefit humanity and tackle the biggest challenges of our time.

Subscribe to our newsletters to be updated with the latest news on innovation, events, articles and reports.

What subscription are you interested in receiving? (Choose at least one subject)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 19 February 2019

The dos and don’ts of influencing policy: a systematic review of advice to academics

- Kathryn Oliver ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4326-5258 1 &

- Paul Cairney 2

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 21 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

86k Accesses

140 Citations

892 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Politics and international relations

- Science, technology and society

A Correction to this article was published on 17 March 2020

This article has been updated

Many academics have strong incentives to influence policymaking, but may not know where to start. We searched systematically for, and synthesised, the ‘how to’ advice in the academic peer-reviewed and grey literatures. We condense this advice into eight main recommendations: (1) Do high quality research; (2) make your research relevant and readable; (3) understand policy processes; (4) be accessible to policymakers: engage routinely, flexible, and humbly; (5) decide if you want to be an issue advocate or honest broker; (6) build relationships (and ground rules) with policymakers; (7) be ‘entrepreneurial’ or find someone who is; and (8) reflect continuously: should you engage, do you want to, and is it working? This advice seems like common sense. However, it masks major inconsistencies, regarding different beliefs about the nature of the problem to be solved when using this advice. Furthermore, if not accompanied by critical analysis and insights from the peer-reviewed literature, it could provide misleading guidance for people new to this field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Systematic review and meta-analysis of ex-post evaluations on the effectiveness of carbon pricing

Identity and inequality misperceptions, demographic determinants and efficacy of corrective measures

Introduction.

Many academics have strong incentives to influence policymaking, as extrinsic motivation to show the ‘impact’ of their work to funding bodies, or intrinsic motivation to make a difference to policy. However, they may not know where to start (Evans and Cvitanovic, 2018 ). Although many academics have personal experience, or have attended impact training, there is a limited empirical evidence base to inform academics wishing to create impact. Although there is a significant amount of commentary about the processes and contexts affecting evidence use in policy and practice (Head, 2010 ; Whitty, 2015 ), the relative importance of different factors on achieving ‘impact’ has not been established (Haynes et al., 2011 ; Douglas, 2012 ; Wilkinson, 2017 ). Nor have common understandings of the concepts of ‘use’ or ‘impact’ themselves been developed. As pointed out by one of our reviewers, even empirical and conceptual papers often routinely fail to define or unpack these terms—with some exceptions (Weiss, 1979 ; Nutley et al., 2007 ; Parkhurst, 2017 ). Perhaps because of this theoretical paucity, there are few empirical evaluations of strategies to increase the uptake of evidence in policy and practice (Boaz et al., 2011 ), and those that exist tend not to offer advice for the individual academic. How then, should academics engage with policy?

There are substantial numbers of blogs, editorials, commentaries, which provide tips and suggestions for academics on how best to increase their impact, how to engage most effectively, or similar topics. We condense this advice into 8 main tips, to: produce high quality research, make it relevant, understand the policy processes in which you engage, be accessible to policymakers, decide if you want to offer policy advice, build networks, be ‘entrepreneurial’, and reflect on your activities.

Taken at face value, much of this advice is common sense, perhaps because it is inevitably bland and generic. When we interrogate it in more detail, we identify major inconsistencies in advice regarding: (a) what counts as good evidence, (b) how best to communicate it, (c) what policy engagement is for, (d) if engagement is to frame problems or simply measure them according to an existing frame, (e) how far to go to be useful and influential, (f) if you need and can produce ground rules or trust (g) what entrepreneurial means, and (h) how much choice researchers should have to engage in policymaking or not.

These inconsistencies reflect different beliefs about the nature of the problem to be solved when using this advice, which derive from unresolved debates about the nature and role of science and policy. We focus on three dilemmas that arise from engagement—for example, should you ‘co-produce’ research and policy and give policy recommendations?—and reflect on wider systemic issues, such as the causes of unequal rewards and punishments for engagement. Perhaps the biggest dilemma reflects the fact that engagement is a career choice, not an event: how far should you go to encourage the use of evidence in policy if you began your career as a researcher? These debates are rehearsed more fully and regularly in the peer-reviewed literature (Hammersley, 2013 ; de Leeuw et al., 2008 ; Fafard, 2015 ; Smith and Stewart, 2015 ; Smith and Stewart, 2017 ; Oliver and Faul, 2018 ), which have spawned narrative reviews of policy theory and systematic reviews of the literature on the ‘barriers and facilitators’ to the use of evidence in policy. For example, we know from policy studies that policymakers seek ways to act decisively, not produce more evidence until it speaks for itself; and, there is no simple way to link the supply of evidence to its demand in a policymaking system (see Cairney and Kwiatkowski, 2017 ). We draw on this literature to highlight inconsistencies and weaknesses in the advice offered to academics.

We assess how useful the ‘how to’ advice is for academics, to what extent the advice reflects the reality of policymaking and evidence use (based on our knowledge of the empirical and theoretical literatures, described more fully in Cairney and Oliver, 2018 ) and explore the implications of any mismatch between the two. We map and interrogate the ‘how to’ advice, by comparing it with the empirical and theoretical literature on creating impact, and on the policymaking context more broadly. We use these literatures to highlight key choices and tensions in engaging with policymakers, and signpost more useful, informed advice for academics on when, how, and if to engage with policymakers.

Methods: a systematic review of the ‘how to’ literature

Systematic review is a method to synthesise diverse evidence types on a clear defined problem (Petticrew and Roberts, 2008 ). Although most commonly associated with statistical methods to aggregate effect sizes (more accurately called meta-analyses), systematic reviews can be conducted on any body of written evidence, including grey or unpublished literature (Tyndall, 2008 ). All systematic reviews take steps to be transparent about the decisions made, the methods used to identify relevant evidence, and how this was synthesised to be transparent, replicable and exhaustive (resources allowing) (Gough et al., 2012 ). Primarily they involve clearly defined searches, inclusion and exclusion processes, and a quality assessment/synthesis process.

We searched three major electronic databases (Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar) and selected websites (e.g., ODI, Research Fortnight, Wonkhe) and journals (including Evidence and Policy, Policy and Politics, Research Policy), using a combination of terms. Terms such as evidence and impact were tested to search for articles explaining how to better ‘use’ evidence, or how to create policy ‘impact’. After testing, the search was conducted by combining the following terms, tailored to each database: ((evidence or science or scientist or researchers or impact), (help or advi* or tip* or "how to" or relevan*)) policy* OR practic* OR government* OR parliament*). We checked studies on full text where available and added them to a database for data-extraction. We conducted searches between June 30th and August 3rd 2018. We identified studies for data extraction when they covered these areas: Tips for researchers, tips for policymakers, types of useful research / characteristics of useful research, and other factors.

We included academic, policy and grey publications which offered advice to academics or policymakers on how to engage better with each other. We did not include: studies which explored the factors leading to evidence use, general commentaries on the roles of academics, or empirical analyses of the various initiatives, interventions, structures and roles of academics and researchers in policy (unless they offered primary data and tips on how to improve); book reviews; or, news reports. However, we use some of these publications to reflect more broadly on the historical changes to the academic-policy relationship.

We included 86 academic and non-academic publications in this review (see Table 1 for an overview). Although we found reports dating back to the 1950s on how governments and presidents (predominantly UK/US) do or do not use scientific advisors (Marshall, 1980 ; Bondi, 1982 ; Mayer, 1982 ; Lepkowski, 1984 ; Koshland Jr. et al., 1988 ; Sy, 1989 ; Krige, 1990 ; Srinivasan, 2000 ) and committees (Sapolsky, 1968 ; Wolfle, 1968 ; Editorial, 1972 ; Walsh, 1973 ; Nichols, 1988 ; Young and Jones, 1994 ; Lawler, 1997 ; Masood, 1999 ; Morgan et al., 2001 ; Oakley et al., 2003 ; Allen et al. 2012 ). The earliest publication included was from 1971 (Aurum, 1971 ). Thirty-four were published in the last two years, reflecting ever increasing interest in how academics can increase their impact on policy. Although some academic publications are included, we mainly found blogs, letters, and editorials, often in high-impact publications such as Cell, Science, Nature and the Lancet. Many were opinion pieces by people moving between policy officials and academic roles, or blogs by and for early career researchers on how to establish impactful careers.

The advice is very consistent over the last 80 years; and between disciplines as diverse as gerontology, ecology, and economics. As noted in an earlier systematic review, previous studies have identified hundreds of factors which act as barriers to the uptake of evidence in policy (Oliver et al., 2014 ), albeit unsupported by empirical evidence. Many of the advisory pieces address these barriers, assuming rather than demonstrating that their simple advice will help ease the flow of evidence into policy. The pieces also often cite each other, even to the extent of using the exact phrasing. Therefore, the combination of previous academic reviews with our survey of ‘how to’ advice reinforces our sense of ‘saturation’, in which we have identified all of the most relevant advice (available in written form). In our synthesis, using thematic analysis, we condense these tips into 8 main themes. Then, we analyse these tips critically, with reference to wider discussions in the peer-reviewed literature.

Eight key tips on ‘how to influence policy’

Do high quality research.