What is Horror? Definition and Examples in Film

W hy are humans drawn to the horror genre? From books to film, we can’t seem to get enough of what scares us most. In this article, we will look at the definition of horror and why we enjoy the genre so much. We will also look at a brief history of American cinema and how horror has evolved over the years. While this article will provide a general definition of horror, the genre is open to interpretation. After all, what is horror to you, is Child’s Play to me.

Watch: What Makes a Great Jump Scare?

Subscribe for more filmmaking videos like this.

Define Horror

The horror genre explained.

Horror is one of the most popular genres in storytelling. What began in literature can now be found in movies, television, theatre, and video games. The horror genre has been divided into many sub-genres with their own definitions and criteria. Before we get to those, let's define horror at a basic level:

HORROR DEFINITION

What is horror.

Horror is a genre of storytelling intended to scare, shock, and thrill its audience. Horror can be interpreted in many different ways, but there is often a central villain, monster, or threat that is often a reflection of the fears being experienced by society at the time. This person or creature is called the “other,” a term that refers to someone that is feared because they are different or misunderstood. This is also why the horror genre has changed so much over the years. As culture and fears change, so does horror.

What are some defining elements of the horror genre?

- Themes : The horror genre is often a reflection of the culture and what it fears at the time (invasion, disease, nuclear testing, etc.).

- Character Types : Besides the killer, monster, or threat, the various sub-genres contain certain hero archetypes (e.g., the Final Girl in Slasher movies).

- Setting : Horror can have many settings, such as: a gothic castle, small town, outer space, or haunted house. It can take place in the past, present or future.

- Music : This is an important facet in the horror genre. It can be used with great effect to build atmosphere and suspense.

Horror Subgenres

Different types of horror movies.

The horror genre has given birth to many sub-genres and hybrids of these various types. Each has its own unique themes, but all of them share one common goal: FEAR.

Found Footage

The point-of-view takes place from the perspective of a camera. Famous titles include The Blair Witch Project and Rec .

Lovecraftian

Focuses on cosmic horror. Monsters are beings beyond our comprehension. Often incorporates science fiction, including horror classics like Alien and The Thing .

Psychological

This sub-genre focuses on the horror of the mind. What is real? What is madness? Two great psychological horror movies are Silence of the Lambs and Jacob’s Ladder .

Science Fiction

Focuses on the horror and consequences of technology. Monsters are often aliens or machines. Two great sci-fi horror movies are The Blob and War of the Worlds .

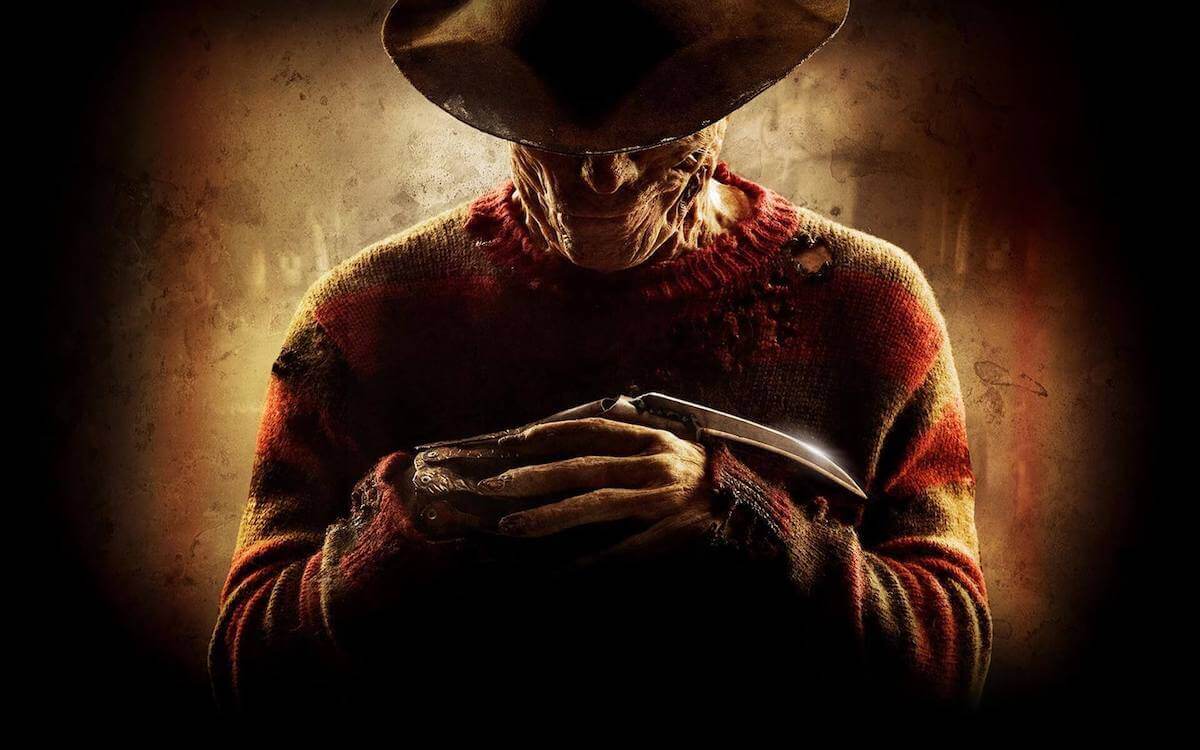

The monster is a psychopath with a penchant for bloody murder. Often focuses on the punishment of promiscuous teenagers. Popular movies include Halloween and A Nightmare on Elm Street .

Supernatural

Focuses on the afterlife. Primary creatures include ghosts and demons. Great titles include Poltergeist and The Exorcist .

Similar to slasher; focuses on the punishment of people. The villain takes pleasure in the physical and psychological torment of victims. Famous movies include Hostel and Saw .

One of the oldest horror sub-genres in which icons like Dracula feed on human blood. Some of the best vampire movies include Nosferatu and Interview with the Vampire .

When a full moon is out, beware of these beastly shape-shifters. The best werewolf movies include An American Werewolf in London and The Wolf Man .

A group of survivors is usually attacked by a horde of flesh-eating undead. Night of the Living Dead is considered one of the best zombie movies along with 28 Days Later... and Shaun of the Dead .

A History of Horror Movies 1896-2018

Horror vs thriller, the relationship of horror and thriller.

While the two genres are often confused, there is a clear difference between horror and thriller movies. Horror movie rules demand violence and a monster that appears early and relatively frequently. The climax revolves around a final fight or an escape from the monster. The "monster" in horror is typically "unnatural" or even "supernatural," whereas thrillers tend to rely on human threats.

In a thriller, there is much more mystery and discovery. Tensions rise as the protagonist gets closer to discovering the evil threat. The climax revolves around a big reveal, such as the true intentions of the villain.

The two genres con blend, of course, such as the modern horror/thriller Get Out (2017). Something like Halloween might also be considered a crossover since the killer is human but he exhibits supernatural abilities — like how he never seems to die when he's "killed."

Now that we've covered our horror film definition, let's take a look back at a history of horror movies. Through the decades, the horror movie has evolved to reflect what we we fear the most, as explained in this video.

The Horror Genre and Cultural Fears

1930’s horror, horror and the depression.

The 1930s was a tough period for America. We were in the midst of the Great Depression and Americans were feeling more desperate than ever before. Despite the economic turmoil, people spent what little they had on entertainment, like movies. One of the first great American horror films that garnered much popularity was Dracula (1931), based on the novel by Bram Stoker. And it set the standard for the Best Vampire Movies thereafter.

But why was Dracula so terrifying? Americans were afraid of European influence. World War I ended only 13 years prior. The American mindset was still heavily influenced by the atrocities that took place. Combined with the influx of European immigrants, people were afraid of outsiders corrupting American culture. Someone had to be the scapegoat.

Another film that was a reflection of the fears of the time was Frankenstein (1931), based on the novel by Mary Shelly. This movie created a more sympathetic monster; one that was fleeing from the oppression of his creator.

Below is the original disclaimer that ran before the movie began. It is a warning played up for dramatic effect ("...it might even horrify you!").

Frankenstein Disclaimer

Americans felt as though they that their government had failed them. They blamed their leaders for their misfortune, much like how Dr. Frankenstein failed to protect his creation.

A recurring theme in horror is that the monster is often mankind itself. The villagers lashed out against something they didn’t understand, becoming monsters themselves.

What is Horror? Dracula (1931)

1950s horror, horror in the '50s.

World War II ended in 1945, but it left a huge mark on the world, both literally and figuratively. The use of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki gave way to a new era of fear in the nuclear age. The consequences of mankind’s use of science and technology would become a common theme.

Often not thought of as horror, Godzilla (1954) is a Japanese film that came to America. It was a response to the bombs used by the U.S. In this story, an animal is transformed by nuclear radiation into a giant monster and terrorizes the country. With the advent of the nuclear age, many questions and fears were brought up with this powerful but dangerous energy source.

The monster movie has a rich tradition within the horror genre, dating back to the very first movies. Do yourself a favor and watch this documentary on the history of the monster movie.

History of the Horror Genre • Monster Movies

The 50’s also gave to the Red Scare and the fear of communism. The theme of invasion became prevalent in many monster movies. Science fiction would blend with the horror genre, giving birth to films such as War of the Worlds (1953) and Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956).

In the first film, aliens begin an invasion of earth in a small town, indicative of a communist attack. In the second film, humans are replaced with alien duplicates, which represents the fear of communism overtaking democracy.

What is Horror? War of the Worlds (1953)

1960s-'70s horror, when the monster became human.

The 1960s-'70s was a period of uncertainty and violence for America. We were in the midst of the Vietnam War, a conflict that caused much controversy. For the first time, the U.S. was no longer in the right for a global conflict. The violence committed by men led to the fear of what we as a species were capable of.

Night of the Living Dead (1968) came as a result of this fear and uncertainty. The monsters, which looked very human, would mercilessly attack, kill and devour people. What made the zombies most terrifying was that they could take on the appearance of our loved ones. If we cannot trust our fellow human, who can we trust?

Thanks to a copyright error, Night of the Living Dead belongs in the public domain. That means you can watch it for free right now. Any self-respecting horror genre fan has to watch this movie.

Watch Night of the Living Dead in its entirety

The 70’s were also known for the increase in news coverage on serial killer murders. Media outlets reported on these maniacs as if they were celebrities. People were afraid of the monster next door coming by and killing them in their homes.

This gave rise to the first “slasher,” Halloween (1978). Despite appearing human, Michael Myers was an unstoppable killer that stalked his victims with murderous intent. Slashers grew immensely in popularity, even affecting movies that are not slashers .

The slasher sub-genre would also explore the subject of morality. The sexually promiscuous would be punished and violently murdered, while the moral “Final Girl” would survive to the bitter end.

One would think that these human monsters would drive people away from horror. But the blood-soaked films would make the genre more popular than ever.

What is Horror? Halloween (1976)

1980s-'90s horror, what is self-aware horror.

Coming out of the serial killer era in the '70s, the '80s would continue the trend of slashers with a massive influx of these movies. Friday the 13th , A Nightmare on Elm Street and even Halloween would spawn numerous sequels, each one more absurd than the last.

Hitting a breaking point, the horror genre became more "aware" of itself in the form of Scream (1996). Though very much still a slasher, this film acknowledged the well-worn tropes established by its predecessors, such as the Final Girl.

What is Horror? Scream (1996)

Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) would take the trope of the weak high school girl and turn her into a monster killer. While the protagonist, Buffy, was killing vampires and other monsters, she and her friends would still experience the woes of being a teenager.

The '90s would also pave the way for a new sub-genre: found footage. The Blair Witch Project (1999) gave the audience the point-of-view of a camera, putting them in the shoes of the victims. This made the horror more personal for viewers, revitalizing the genre as a whole.

Horror Sub-genres • Found Footage

2000s horror, when the horror film took a dark turn.

After 9/11, the war on terror would spawn a generation of films that would redefine what horror is: torture. The prospect of psychos capturing and torturing their victims, both physically and psychologically proved to be a box office success.

Perhaps the most notorious of these is Saw (2004). In this film, a sociopath captures several people and forces them to play his sadistic games if they want to survive. This gruesome concept would spawn a plethora of sequels and copycats, flooding the market and coining a new term for the excess of violence: torture porn.

Global fears and international terror attacks made the end of the world seem more plausible. People became more fascinated than ever over the prospect of a catastrophe like a zombie apocalypse.

As such, the horror genre would reflect this with shows such as The Walking Dead (2010-present). How would any of us survive? How can something so overwhelming ever be stopped? As zombie movies grew in popularity, so did the number of movies. And as this video explains, what we now call "zombies" began as something quite different.

Horror Sub-genres • Zombies

The future of horror, what is horror today.

To say we live in a new world would be an understatement. The COVID-19 pandemic has changed the way we act, think and feel. Global culture as a whole has changed and it will continue to do so for some time. As such, expect the horror genre to reflect this evolution of fear. Don’t be surprised when an influx of movies revolving around isolation and global pandemics hits theaters.

There has been a sort of renaissance of horror movies in the last decade that has been quite excited to watch. Films like The Witch , It Follows and Hereditary have been dubbed "elevated horror" — a divisive term to say the least. Whatever we call them, they are all still really strong and effective horror movies. Here's a breakdown of Midsommar and how the shape of the horror genre continues to evolve.

How Ari Aster Uses the Background • Subscribe on YouTube

The best horror movies of all time.

We just covered a very broad horror genre definition and there is a lot more to explore. We've been talking a lot about the horror genre but now it's time to face our fears and actually watch some. Through the last century, across genre to sub-genre, from ghouls to goblins, here are the Best Horror Movies of All Time.

Up Next: Best Horror Movies →

Showcase your vision with elegant shot lists and storyboards..

Create robust and customizable shot lists. Upload images to make storyboards and slideshows.

Learn More ➜

I would like to know the 5 elements of horror but I liked it

This was amazing!

On Facebook, many horror devotees stated decisively that "FREAKS" 1932 was the first horror movie with a female lead named Cleopatra. Cleopatra is transformed into a deformed duck in this famous movie. However, to my way of thinking and perhaps yours (Jonathan Scott), a deformed duck is not particularly horrifying nor does it fit your definition of an alien, monster or a human threat. What do you think? Does FREAKS somehow fit into the horror genre?

Wow… was that a ride or what?!?!… Thank you for that great knowledge. I just stepped onto the scene and into the Movie Industry with a wealth of knowledge. Thank You

NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD (1968) is a fascinating movie I've seen many times. It's funny: the film stock is grainy, the acting is sketchy, black-and-white means you never see red blood, the music is generic potboiler they found somewhere and grafted it on. Yet it remains for me such an unnerving, iconic picture. Its very flaws actually seem to enhance the horror effect…

I like horror that emerges from very plausible, quotidian places… as with THE EXORCIST. In fact, I don't need ski-masks, gothic mansions or weird costumes… I love the horror that comes from being alive everyday, as with BLACK SWAN. JACOB'S LADDER works this way, too.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Pricing & Plans

- Product Updates

- Featured On

- StudioBinder Partners

- Ultimate Guide to Call Sheets

- How to Break Down a Script (with FREE Script Breakdown Sheet)

- The Only Shot List Template You Need — with Free Download

- Managing Your Film Budget Cashflow & PO Log (Free Template)

- A Better Film Crew List Template Booking Sheet

- Best Storyboard Softwares (with free Storyboard Templates)

- Movie Magic Scheduling

- Gorilla Software

- Storyboard That

A visual medium requires visual methods. Master the art of visual storytelling with our FREE video series on directing and filmmaking techniques.

We’re in a golden age of TV writing and development. More and more people are flocking to the small screen to find daily entertainment. So how can you break put from the pack and get your idea onto the small screen? We’re here to help.

- Making It: From Pre-Production to Screen

- What is Method Acting — 3 Different Types Explained

- Ultimate Guide to Sound Recording: Audio Gear and Techniques

- How to Make a Production Call Sheet From Start to Finish

- What is Call Time in Production & Why It Matters

- How to Make a Call Sheet in StudioBinder — Step by Step

- 69 Facebook

- 11 Pinterest

The Codes and Conventions of Horror Films

Introduction.

Horror films often feature the dark and ominous atmospheres of dimly lit rooms, nightmarish music, and characters who should not be venturing down into their basements alone. Perhaps the house is cursed by malevolent spirts or the rural community is being terrorised by a masked maniac.

We enjoy watching horror films because they provoke a pleasing sort of terror.

It does not matter if the story takes place in an old graveyard, the haunted woods at the end of the lane, or in the vacuum of deep space where no one can hear you scream. The film just has to be scary. That is why Brigid Cherry (2009) argued the “function of horror to scare, shock, revolt or otherwise horrify the viewer” was more important to the definition of the genre compared to “any set of conventions, tropes or styles”.

As filmmakers continue to find new ways to frighten the audience, we are going to focus on the essential conventions and aesthetics of the genre , its enduring appeal, and why companies continue to profit from horror films.

The Iconography of Horror Films

Iconography refers to the pattern of signs which are closely associated with certain genres. We already know horror films are set in bleak and gloomy locations, such as haunted houses, abandoned buildings, small towns, and remote cabins in the woods. There is usually a sense of isolation and confinement in these dark spaces. The audience will expect to hear the wind howling across the desolate landscape and the old floorboards to creak with every step.

The poster for The Conjuring uses some of codes and conventions of horror to grab the audience’s attention. First, the title denotes paranormal tricks and demonic possession. The references to Saw and Insidious establishe the director’s genre credibility. Of course, the lonely farmhouse looks forsaken along the rough and misty trees. This isolation increases the sense of threat because its occupants will be helpless against the evil forces.

Perhaps the most sinister signifier is the noose tied to the bare and misshapen tree. Did you notice the shadow of the girl? The combination of these elements is the punctum designed to strike fear into the audience.

Finally, the macabre tone is reinforced by heavy, grey sky and the dying leaves scattered across the field. The poster is certainly trying to make the audience feel uneasy and want to experience this nightmare for themselves.

Many horror posters will contain variations of this fusion of codes – their settings and props will be just as menacing. We might see incomplete glimpses of the monster, such as a close up of its hideous fangs or its shadow cast against the wall, so its reveal will be shocking when it appears the big screen.

In his discussion on genre, Steve Neale (1980) wrote “all the resources of the costume and make-up department are mobilised” in horror films to “frighten and terrify” the audience. These monsters are coming to get you, Barbara.

Most of the characters will not make it to the closing credits, but another common trope in horror movies is the “final girl”. She is the last survivor of a group of friends who defeats villain. Inevitably, there will be plenty of guts and gore along the way.

Technical Codes

Imagine paying a penny in the early days of cinema to see the black and white film stock being projected onto the large screen. There is no doubt that flickering, spectral quality made the characters and settings seem scarier. Even more recent films shot on digital cameras, such as The Blair Witch Project or 28 Days Later , can give the footage a gritty reality which will terrify the audience.

The genre has always exploited a range of filmmaking techniques to elicit fear.

Music and Sound Effects

A lot of effort and innovation goes into creating a scary mix of dialogue, effects, and music.

Orchestral scores are a familiar, unnerving presence in horror films. Dissonant chords and demonic whispers help create the unsettling atmospheres and deepen our understanding of the characters. How many times have you heard the music build to a crescendo during moments of high tension, such as a frenetic chase scene, or jump scares punctuated by sudden and jarring sounds? Composers will also use motifs to signal the arrival of certain events – epitomised by John William’s famous theme each time the shark appears in Jaws .

Another famous piece of music is Bernard Hermann’s score for Psycho which uses an amazing range of deep bass sounds and screeching violins to great effect. Perhaps the budget was only enough for string instruments. This article by Aaron Gilmartin is a good introduction to the composition and contains relevant extracts from the film.

Synthesisers became popular in horror films produced in the 1980s because they were more cost-effective. Listen to John Carpenter’s distinctive theme for Halloween – its disturbing pattern of pulses will have you looking over your shoulders.

Music can enhance the emotional impact of a horror film, but diegetic sound is just as important. When the protagonist moves down the dark hallway of the farmhouse, the audience will expect to hear the nerve-tingling creaks of old floorboards – the awful silence in between each footstep should emphasise the character’s vulnerability. The sound of a distant clock ticking can develop a sense of impending danger and the awful buzz of chainsaw will surely disturb any viewer.

An interesting example is the motion tracking beep in Aliens when the increasing speed indicates the vicious monsters are getting closer and closer.

This scene also stresses the importance of dialogue. Private Hudson counts down to 6 and Ripley exclaims, “That can’t be. That’s inside the room.” The effective use of sound can be the difference between a good horror film and a truly terrifying one.

Lighting Design

Lighting sets the tone of the film. Bright and well-lit scenes feel safe, comforting and uplifting. By contrast, dark and dimly lit spaces create a sense of uncertainty and danger by playing on our natural fear of the unknown. When a character is alone in the dark, they are cut off from others which should make them seem more vulnerable.

Filmmakers also use deep shadows to obscure details and only show glimpses of the horror. Leaving the signifier to the viewer’s imagination can be more terrifying than actually seeing the monster or villain.

Light can be just as effective in creating a sense of dread and unease. A harsh spotlight might draw attention to a character’s face, making their frightened expression more intense for the viewer, or a flicking strobe light could highlight the monster’s erratic movements. Have you ever held a torch under your face while you told your friends a ghost story? This effect is called uplighting.

Consider the lighting design in this scene from The Conjuring which relies on light bulbs and matches to terrify the audience.

Derived from the Italian words chiaro (light) and scuro (dark), the term chiaroscuro refers to the use of strong contrasts between light and dark in a composition. In horror films, the effect can make the viewer feel incredibly anxious about what is lurking in those shadows.

This iconic shot from The Exorcist makes excellent use of the technique.

The image of Father Merrin arriving at the home to perform the exorcism was used all over the world for the film’s original poster. Symbolising the intense battle between good and evil, the chiaroscuro draws our attention to the connection between the silhouetted priest and the room where the demon has possessed the innocent girl.

By manipulating light and shadow, filmmakers can deliver a cinematic experience that is both visually striking and emotionally terrifying.

Framing the Horror

In cinematography, framing refers to the way the image is composed within the boundaries of the screen. Filmmakers have to decide what to include in the shot and how to arrange those elements in the frame to elicit the right response from the audience.

Wide shots are used to establish the setting, but they can also encode a sense of isolation and vulnerability by showing the characters in large, empty spaces. If a director wants the audience to connect with a character’s fear, they can tighten the camera into a close up of their face. Close ups are often used to highlight details of a monster’s face or body to make it more terrifying. The audience might even feel like they are the ones being hunted by the monster when the director cuts to a point-of-view shot.

Low-angle shots can make the villains appear larger and more powerful, while high-angle shots can make victims seem small and exposed. Tilted angles are disorientating and disrupt our comfortable view of the world.

Camera Movement and Editing

The process of selecting, arranging, and manipulating the different shots into a congruent narrative or visual sequence is called editing. These decisions can make or break a horror film. Have a look at the opening shots of It Follows .

The wide frame pans around the suburban street suggesting there is some sort of invisible danger stalking the young girl. There is a tremendous sense of dread encoded in that shot. The first take lasts an unnerving one minute and fifty seconds before we cut to an interior shot of the car. It is an over the shoulder shot. When Annie turns around to see if she is being followed, the fear is obvious in her eyes.

The third shot is another wide frame. She looks completely lost in that horizon between the sand and black sky. Even in the next shot, which is tighter on the character, encodes her vulnerability.

Annie reacts to the hidden threat, and we cut to a POV shot. The lights of the car make it appear demonic, especially the red taillights. Perhaps the evil force is hidden in the empty spaces either side. Then there is the shock cut. The appearance of her broken body is sudden and unexpected. Horrifying.

In this next sequence, the protagonist is in school when she notices a strange figure in the distance.

The slow push in, which moves the audience closer to the window, is intercut with Jay’s increasing anxiety. The more the old woman dominates the frame, the greater the threat. Jay’s distress is reinforced by the close up and then wide frame of her awkwardly leaving class.

The Steadicam follows her around the school corridor. This camera movement suggests she is disorientated by her distress, especially the image of her walking away from the lens cutting to a shot of her walking towards the audience.

When she realises the old woman is in the corridor, the smoother camera dolly pulls back in each shot, almost invading the audience’s space. The series of quick cuts intensifies the conflict between the characters.

The Interplay of Codes

Steve Neale (1980) argued cinema was a “semiotic process” and meaning was constructed through the “interplay of codes”. Horror films are “specific variations” of these codes. It is the combination of scary visual elements, frightening music and diegetic sound, careful lighting design, and cinematography which provokes that pleasing sort of terror we want to experience when we sit down in our comfortable seats to watch a horror film.

The Narrative of Horror

Horror films explore a variety of themes that tap into our deepest fears and anxieties, raise questions regarding our mortality and what lies beyond, and depict the darker aspects of human nature. Some stories explore the psychological impact of trauma, often featuring characters who are struggling with past events or mental illness. Other films feature a vengeful antagonist seeking revenge for perceived wrongs, creating a sense of moral ambiguity and justice.

Neale (1980) suggested “the disruptions in horror films are often violent”. The gruesome monster attacks the isolated village, a wicked demon takes possession of an innocent child, or a crazed killer begins their terrible revenge on the group of teenagers. Moving the narrative into a state of disequilibrium , these inciting incidents are “often linked to questions about being human and what is natural”.

The narratives obviously rely on action codes – the protagonist closes the bathroom cabinet to reveal the stalker is standing behind them or the vicious dogs chase our heroes through the foggy cemetery.

The Conjuring’s poster also draws attention to the film’s use of enigma codes with the reference to the “true case files of the Warrens”. The two demonologists, Ed and Lorraine Warren, agree to investigate the origins of the dark forces which are haunting the farmhouse. They soon discover the terrible story of the witch and her unholy sacrifices to the devil.

The Japanese horror film Ringu is also driven by enigma codes because the protagonist is a journalist who sets out to uncover the truth about a series of bizarre deaths. The clues lead her the tragic story of Sadako who could project her rage onto video tapes.

We might try to classify horror films into the genre of order because the central conflicts are “externalized, translated into violence, and usually resolved through the elimination of some threat to the social order”. In many early Hollywood studio productions, the monsters were defeated by the end of the story, providing reassuring and confident messages to the audience. More recently, in The Conjuring , for example, the curse is lifted and the witch is condemned to hell. Despite The Mist’s incredibly grim ending, the army are exterminating the creatures and saving the world.

Thomas Schatz (1981) suggested a “genre film’s resolution may reinforce the ideology of the larger society”. He also emphasised the narratives could “challenge and criticize” our values. Perhaps that is why horror films tend to have more ambiguous conclusions.

A great example is when Damien turns to the camera in The Omen , breaking the fourth wall, and smiles at the audience. The image of the devil relishing his victory leaves us with despair.

Horror Subgenres and Hybrids

Cherry (2009) argued the horror genre was “constantly shifting” with “new conceptual categories in order to keep on scaring the audience”. Her outline of these subgenres is a good summary of the different forms of horror.

The Gothic refers to films based on classic tales of horror, often adapting pre-existing horror monsters or horrifying creatures from novels and mythology. Cherry classified films which involved “interventions of spirits, ghosts, witchcraft, the devil, and other entities into the real world” as supernatural, occult and ghost films.

Psychological horror films explore psychological states and psychoses, including criminality and serial killers. Monster movies feature invasions of the everyday world by natural and extra-terrestrial creatures leading to death and destruction. Slashers portray groups of teenagers menaced by a stalker, set in domestic and suburban spaces. There are also body horror and splatter films, including postmodern zombie stories.

Filmmakers borrow codes and conventions from other genres, such as science fiction, war and even westerns, to find new ways of terrifying the audience.

Finally, Cherry noted “what might be classed as the essential conventions of horror to one generation may be very different to the next”, so the genre will continue to diversify and fragment.

What Makes Horror Films Appealing?

Horror films are constructed to provoke negative emotions from the audience. Some people find the stories too scary and distressing to be enjoyable, but others are eager to experience that thrill of being frightened for many different reasons. Some horror franchises even have dedicated fandoms .

Going to the cinema for a good scare is a chance to escape the horrors in our own lives. In terms of the uses and gratifications theories, this motivation is called diversion. As well as being entertaining, watching a horror film with family or friends can create a shared experience and develop our personal relationships. It is almost a rite of passage for two young lovers on a romantic date to protect each other from the frightening images on the big screen.

Horror films can also be life-affirming because they empower the audience to confront and process their fears in a safe environment. Many story arcs conclude when the evil presence is destroyed, and a new equilibrium is established. Seeing the protagonist defeat the supernatural villain might inspire us to overcome the lack in our own lives.

There might be even deeper psychological explanations for our desire to watch horror films. For instance, Sigmund Freud (1919) argued the “uncanny” signifiers in fairy tales, such as severed hands and re-animation of the dead, could help readers resolve some of the emotional disruptions they experienced in childhood. He also suggested the supernatural themes challenged our rational view of the world and allowed us to imagine spaces beyond our own mortality: “it is no matter for surprise that the primitive fear of the dead is still so strong within us and always ready to come to the surface at any opportunity”.

Sometimes horror films raise interesting questions about our values and ideologies . For instance, The Dawn of the Dead is set in a large shopping mall and is an obvious criticism of our culture of consumerism. Other films might present concerns about the collapse of morality in society.

Of course, some people are simply fascinated by the darker aspects of human nature. When it comes to the gory and visceral horror stories, some thrill-seekers like to push the limits of what is acceptable.

Finally, we can appreciate horror films for their artistic value, especially when filmmakers challenge the conventions of the genre and produce something new.

Scary Profits

Although the industry seems full of creativity and glamour, making films comes with huge financial risks. Some productions will generate significant profits while many others will suffer substantial losses.

Keith Barry Grant (1986) described how the “profit-motivated studio system” in Hollywood “adopted an industrial model based on mass production” and attempted to exploit “commercially successful formulas”. If a particular style of film did well at the box office, the studios would try to replicate that success in their next feature. For instance, Universal Pictures developed Dracula , Frankenstein , and The Mummy in the early 1930s to satisfy the audience’s increasing demand for fantasy horror films. These hits were soon followed by the inevitable sequels Dracula’s Daughter , Son of Frankenstein , and a series of stories based on Kharis, an Egyptian mummy.

In his analysis of the Hollywood studios, David Hesmondhalgh (2013) described three important strategies the production companies used to “minimise the danger of misses” and ensure a return on their investment. This formatting process included a focus on star power, genre films and the development of franchises.

Neale (1980) suggested we liked to repeat our experiences of genre films because “pleasure lies in both the repetition of the signifiers and the fundamental differences”, so producers know there is always an audience ready for the next scary story. It is also worth noting horror films have a clear identity which can make the advertising message more effective.

Importantly, horror films do not need large production budgets. They usually have shorter run times which means less footage needs to be shot and edited. If the story takes place in a single location, such as a haunted house, the production company might save money on fewer sets. The producers can also reduce costs by featuring lesser-known actors.

As long as the genre remain profitable, producers will continue to make horror films.

Cherry, Brigid (2009): “Horror”. Freud, Sigmund (1919): “The Uncanny”. Grant, Barry Keith (1986): “Film Genre Reader”. Hesmondhalgh, David (2013): “The Cultural Industries”. Neale, Steve (1980): “Genre”. Schatz, Thomas (1981): “Hollywood Genres Formulas, Filmmaking, and The Studio System”.

Further Reading

Music Videos and Genre

Iconography

Steve Neale and Genre Theory

Genres of Order and Integration

Thanks for reading!

Recently Added

The Grand Syntagma of Cinema

The Kuleshov Effect

Rule of Thirds

Key concepts.

Stuart Hall’s Reception Theory

Henry Jenkins and Fandom

Action and Enigma Codes

Media studies.

- The Study of Signs

- Ferdinand de Saussure and Signs

- Roland Barthes

- Charles Peirce’s Sign Categories

- Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra and Simulation

- Binary Opposition

- Vladimir Propp

- Tzvetan Todorov

- Quest Plots

- Barthes’ 5 Narrative Codes

- Key Concepts in Genre

- David Gauntlett and Identity

- Paul Gilroy

- Liesbet van Zoonen

- The Male Gaze

- The Bechdel Test

- bell hooks and Intersectionality

- The Cultural Industries

- Hypodermic Needle Theory

- Two-Step Flow Theory

- Cultivation Theory

- Stuart Hall’s Reception Theory

- Abraham Maslow

- Uses and Gratifications

- Moral Panic

- Camera Shots

- Indicative Content

- Statement of Intent

- AQA A-Level

- Exam Practice

Subgenres of Horror Films Explained

What’s Your Favorite Genre of Horror?

Horror is one of the most entertaining and studied genres in filmmaking. The threshold to make a horror film is relatively low. It’s an opportunity for creatives to experiment with effects and revive folklore storytelling devices. Filmmakers use many methods of manipulation to heighten horror and make the viewer fear whatever is coming next. Depending on the intended reaction, some techniques include the classic jump scare, mounting suspense, and over-extended scenes to make audiences squirm in their seats a little longer. These movie techniques are frequently used in almost all subgenres of horror films. People are drawn to horror movies because there isn’t just one type of horror film —there are many.

Horror includes many subgenres that date back to the beginning of film history. Take for instance the silent era of filmmaking. Nosferatu (1922) was the first film to feature the vampire, a European folklore figure that exists on the warm blood of a living victim. Vampires are now ubiquitous in the horror movie genre and have hit the mainstream with blockbuster movies such as The Twilight series.

October is the harbinger of horror, but one does not need to wait for a certain season to enjoy a rush of adrenaline from a good scary movie. Here are the popular subgenres of horror films viewers can enjoy year round.

10 Popular Subgenres of Horror Films

Demonic possession.

Sometimes thought of as supernatural horror, this subgenre plays into the unknown of the human experience. Demons have been part of historical storytelling for centuries. They represent evil in many forms including mythical, religious and supernatural. One of the most known demonic movie examples of all time is William Friedkin’s 1973 movie The Exorcist . Pazuzu , the main demon, is never actually mentioned in the movie, but is arguably the best-known demon of today’s horror movies. As the star character in The Exorcist , Pazuzu is an ancient mythological demon in Mesopotamia who possessed Regan MacNeil played by Linda Blair. The movie skyrocketed Pazuzu to Hollywood fame and helped shape the demonic genre of horror in modern moviemaking.

Paranormal horror is closely related to the demonic subgenre in that it focuses on characters who aren’t living beings. Spirits and ghosts spook viewers and create fear without a physical presence on screen. For example, furniture moves without anyone touching it or a chill passes through the air out of nowhere. Those are elements of paranormal activity that can be from a demon spirit, supernatural power or ghost. Paranormal Activity , The Conjuring , The Amityville Horror , The Omen , Carrie , and Poltergeist are all examples from the Paranormal subgenre.

Vampires, aliens, and giant sea creatures are all antagonists in the Monster movie genre. Unlike their supernatural counterparts, monsters can wreak havoc on a community of people in one fell swoop. Monsters terrorize and kill whatever is in their path and use their strength and size to destroy. Universal Studios popularized the monster genre in Hollywood from the 1930s and ‘50s with Frankenstein, Dracula, the Creature of the Black Lagoon, and many other iconic monsters. Before Universal found success in making horror films, it wasn’t considered a big player during Hollywood’s early years. Once they discovered that audiences loved to be thrilled and simultaneously terrorized by giant monsters, the studio built a media franchise around their monster movies. Today, when you visit the Universal Studios backlot, you’ll see a giant mural with popular monsters painted on an outdoor wall.

Slasher movies focus on villains who are human. Slasher villains are usually serial killers and typically have a high body count by the end of the movie. They stalk their victims and brutally murder the film’s protagonist(s) and anyone who gets in their way. Freddy Krueger, Michael Myers, and Jason Voorhees (better known as Jason) are iconic slasher villains in horror film history. John Carpenter’s 1978 cult classic movie Halloween ushered in the era of masked serial killers as part of the slasher movies genre. Audiences are particularly terrified by the slasher genre because of how close to reality these fictionalized villains make viewers feel.

Zombie movies cross multiple horror subgenres. One part monster movie, one part possession, zombie thrillers make a perfect cocktail of terror. Somehow they are the most difficult villain to kill off and just keep coming back for more. These corpse-like characters are cannibalistic by nature and can infect their victims with a single bite. Shows like The Walking Dead created a cult following for the zombie genre of horror. With 11 seasons spanning from 2010 to 2021, The Walking Dead TV series showcased a horrifying post-apocalyptic story of zombie invasions. The success of the show has kept audiences interested in zombie horror that will likely continue for years to come.

Gore (Splatter)

Also known as the splatter genre, gore is all about the portrayal of graphic violence. Blood, guts and body trauma are classic elements in gore movies. Films in the gore category rely heavily on special effects to disfigure body parts. New filmmakers can experiment with effects and get creative with theatrical makeup. This genre is the most gratuitous of all horror films when it comes to violence and the dismemberment of characters. Classic examples of gore movies include Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead and Eli Roth’s Cabin Fever .

Witches have a long history of mischief in folklore. They use the power of magic to cast spells on their victims turning them into all kinds of tortured beings. Similar to the paranormal genre, witchcraft uses supernatural elements to create fear. Movies like The Witch and Susperia are great examples of the terror caused by witches.

English literature popularized vampire stories, which were basically just ghost stories of the dead returning to haunt the living. It wasn’t until the slowburn success of Dracula that helped launch vampire stories into the mainstream. There have been countless low-budget Dracula movies throughout the years including Horror of Dracula , The Brides of Dracula , Dracula’s Dog . One of the more successful vampire movies (besides, the Twilight Series) is Neil Jordan’s adaptation of the 1976 novel Interview with a Vampire . A young Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt play vampires. The film focuses on Lestat (Cruise) and Louis (Pitt), beginning with Louis’s transformation into a vampire by Lestat in 1791.

Psychological

Psychological horror is not about what we see on the screen but how it makes us feel. This genre plays tricks on the viewers’ mind by creating paranoia. A viewers’ emotional state is heavily influenced by psychological horror. Since this type of horror can feel a little too real compared to the other genres (gore and monsters), people may walk away feeling uneasy. The main characters in these types of horror movies are mentally unstable or emotionally disturbed to the point of being violent. One of the best examples of the psychological horror genre is Stanley Kurbrick’s The Shining starring Jack Nicholoson. From the beginning of the movie you can see Jack Torrence slowly turn more mad with each developing scene.

Comedic horror is possibly the most fun of all horror movies out there. It’s a subgrene that is equally funny as it is scary. It takes the viewer to complete opposite ends of the horror spectrum resulting in a rollercoaster of emotions. Classic examples of comedy-horror films include Scream , Shuan of the Dead , and The Cabin in the Woods.

Find Out More

- Request More Info

- Book a Tour

- High School Outreach

- Academic Catalog

- Call: 323-860-0789

- Toll Free: 888-688-5277

- Campus Alerts

- COVID-19 FAQ

- Careers at L.A. Film School

Students & Alumni

- Student Portal

- Student FAQs

- Academic Calendar

- Student Records

- Student Store

- Alumni Network

- Career Development

- Make a payment

- Graduation FAQ

- Request Transcripts

Disclosures / Legal

- Accreditation/Approvals

- BPPE Annual Report

- Campus Safety

- Consumer Disclosures

- Do not sell my personal information

- Financial Aid Consumer Information

- Privacy Policy

- School Performance Fact Sheets

- Service Animal Policy

- Title IX Training Materials

- Website Accessibility Statement

- Screenwriting \e607

- Directing \e606

- Cinematography & Cameras \e605

- Editing & Post-Production \e602

- Documentary \e603

- Movies & TV \e60a

- Producing \e608

- Distribution & Marketing \e604

- Festivals & Events \e611

- Fundraising & Crowdfunding \e60f

- Sound & Music \e601

- Games & Transmedia \e60e

- Grants, Contests, & Awards \e60d

- Film School \e610

- Marketplace & Deals \e60b

- Off Topic \e609

- This Site \e600

Defining the Horror Genre in Movies and TV

The horror genre in film and television is one of the most popular money makers. let's dig deeper. .

If you were going to bet on an original movie to be a box-office hit, what genre would you pick? The truth is, there is only one genre that again and again provides hits across both film and television. It's horror.

Even before Jason Blum became one of the most powerful producers in Hollywood, horror has been a valuable bet. Alfred Hitchcock dabbled in the darkness with Psycho , but prior to Norman Bates, we had the Universal monster movies and things like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari .

The horror subgenres are aplenty, and we'll get to them later.

Horror has been around since someone could hold a movie camera. And it's not just on the big screen. We also had shows like The Twilight Zone and Tales from the Crypt scaring our pants off at home.

So today I want to look at the horror genre in movies and television. We'll explore examples, look at current things on the air and in theaters, and talk about why these stories continue to terrify and entertain us.

The Horror Genre Definition

Horror is a genre of film and television whose purpose is to create feelings of fear, dread, disgust, and terror in the audience. The primary goal is to develop an atmosphere that puts the audience on edge and scares them.

Where does the word "horror" come from?

The term actually came from the Old French word " orror," which meant “to shudder or to bristle.”

Horror filmmaking has roots in religions across the world, local folktales, and history. It's a universal genre. Every culture has its scary stories and fears. These elements are meant to exploit the viewer and engage them with the possibility of death and pain.

Most importantly, to be a true horror project, your story should deal in the supernatural. Death, evil, powers, creatures, the afterlife, witchcraft, and other diabolical and unexplainable happenings must be at the story's center.

There is some debate over whether this stuff needs to be supernatural to divide horror from thriller... but we will let you work that out in the comments.

Creeping Around the Horror Genre in Movies and TV

Ghouls, ghosts, slashers, creatures, and gore. Horror film and television focus on adrenaline rides for the audience that dial up the blood, scares, and creative monsters. Horror is always re-inventing old classics, like adding fast zombies and CGI creatures. It also is seen as the most bankable genre with a huge built-in audience.

Horror movies and shows consistently do well.

They have passionate fans, launch successful franchises, and get people excited.

The History of Horror in Film and TV

Even before the earliest cameras were made, people were telling spooky stories.

What was the first horror movie ever? Well, as far as we know, the first horror movie was made by French filmmaker Georges Melies, and was titled Le Manoir Du Diable (AKA The Devil's Castle/The Haunted Castle ). It was made in 1896 and was only about two minutes long.

What's striking to me is that even then, we had certain tropes. That movie contained a flying bat, a medieval castle, a cauldron, a demon figure, and skeletons, ghosts, and witches. There was even a crucifix to destroy the evil.

These kinds of movies and TV shows were initially inspired by literature from authors such as Edgar Allan Poe, Bram Stoker, and Mary Shelley.

Horror has existed as a film genre for more than a century. And things keep changing with the times.

Horror films often reflect where we are as a society and are a good way to track progress and social consciousness.

Check out the infographic below that shows the evolution of the horror film and TV shows.

Tropes and Expectations

The final girl, the "not dead yet" scare, and the dystopian endings.

Horror is famous for having story beats that we come to expect, like jumpscares. Filmmakers must lean into them, but also find ways to subvert. You have subsets of these tropes like haunted houses, slashers, zombies, evil creatures, and others. Each comes with a set of rules.

Scream famously subverts many of these tropes by making its characters aware of them, in a meta sense. This keeps the audience on the edge of their seat. Anyone could die in this world, and anyone could be the killer.

Another film that subverts slasher tropes is Behind the Mask: The Rise of Leslie Vernon . In it, characters address things like the apparent superpowers slashers have. How do they always seem to be one step behind the heroine? It makes for a very different kind of horror film.

Elements of Horror

People go to these movies and shows because they want to feel their heart beating out of control. They want the scare, but also the relief and enjoyment that comes after.

What are some basic elements they might expect?

General elements include ghosts , extraterrestrials , vampires , werewolves , demons, Satanism , evil clowns , gore, torture, vicious animals, evil witches , monsters, giant monsters , zombies, cannibalism , psychopaths , and serial killers.

Horror Subgenres

Horror is a genre that encompasses a wide range of subgenres, each with its own unique themes, tropes, and styles. Here are some of the most notable subgenres within horror:

- Gothic Horror: Known for eerie settings such as haunted castles, it emphasizes terror and suspense. Notable works include Dracula and Frankenstein .

- Psychological Horror: This subgenre focuses on the unstable psychological states of characters. Films like Psycho and The Shining are prime examples.

- Slasher Horror: Features a serial killer as the antagonist who systematically murders people. Key films in this category are Halloween and Friday the 13th .

- Supernatural Horror: Involves supernatural entities like ghosts and demons. Classic examples are The Exorcist and Poltergeist .

- Science Fiction Horror: A mix of science fiction and horror, often featuring aliens or dystopian futures. Alien and The Thing stand out in this subgenre.

- Body Horror: Centers on the distortion or transformation of the human body. Films such as The Fly and Hellraiser exemplify this style.

- Found Footage Horror: The film is presented as discovered video recordings. Notable examples include The Blair Witch Project and Paranormal Activity .

- Monster Horror: Focuses on mythical or scientifically mutated monsters. Iconic films in this subgenre are Godzilla and Jaws .

- Zombie Horror: Features zombies, typically resulting from an epidemic. Night of the Living Dead and 28 Days Later are key films in this category.

- Survival Horror: Emphasizes survival in hostile environments. Examples include The Descent and The Ruins .

Each of these subgenres brings a unique flavor to the horror genre, offering a diverse range of terrifying experiences for audiences.

Horror is such a malleable genre that you can mash it up with almost anything. There are subgenres that involve different kinds of monsters, and there are subgenres that pull in other elements. You can see movies and shows that involve comedy, body, folk history, found footage, Gothic elements, natural elements, slasher, teen, psychological, gore, and many others I'm sure you'll tell me about in the comments.

Here's what you really need to know. There are four main horror areas: Killers, Monsters, Paranormal, and Psychological Horror.

Everything else kind of fits underneath them.

What are Horror Genre Characteristics?

Horror film and TV shows are designed to frighten and panic audiences. You want people leaving theaters or hiding while watching shows because you've invoked our hidden worst fears, often in a terrifying, shocking finale.

The AMC site defines horror as, "Whatever dark, primitive, and revolting traits that simultaneously attract and repel us are featured in the horror genre. Horror films are often combined with science fiction when the menace or monster is related to a corruption of technology, or when Earth is threatened by aliens. The fantasy and supernatural film genres are not synonymous with the horror genre, although thriller films may have some relation when they focus on the revolting and horrible acts of the killer/madman. Horror films are also known as chillers, scary movies, spookfests, and the macabre."

Examples of the Horror Genre in Movies and TV

When we look at movies and TV show within this genre it's hard to narrow down the perfect list of examples. There are so many horror moves and TV shows to pick from, but I wanted to highlight a few here.

I think these are shows and films that you can classify as straight horror, no mashups.

First, Netflix just dropped The Haunting of Bly Manor , a spiritual sequel to their The Haunting of Hill House . From the mind of Mike Flanagan , it takes typical haunted house stories and turns them into a series.

Overall, horror on TV is hard, because you have to develop it in multiple episodes. Usually, mashups work best here, so there's more to talk about. Something like Lovecraft Country excels by using every episode to dig deeper into the horrors of Lovecraft.

When it comes to the cinema, there are thousands I can pick from.

We have horror adaptations like The Shining , or from Mike Flanagan again... Doctor Sleep .

I think Hitchcock's Psycho was so important to the jumps and scares we see today. Or a slow burn like The Sixth Sense , which rocketed the genre forward and helped it be taken seriously again. That hadn't really happened since The Exorcist .

How about Mary Harron 's take on the dark underbelly of corporate America in American Psycho ? There is a wealth of fresh perspectives to be found in the work of horror directors like Karyn Kusama , Coralie Fargeat, and Jennifer Kent.

Of course, we can look at franchises like Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream and even The Conjuring and see how horror takes off and becomes part of the cultural lexicon.

Movies and shows like this take off because audiences cannot get enough of the thrills and chills. Whether it's the spooky season or now, horror can take over and keep people on edge. You can release these movies around any time of year, and they can be a hit.

You can put them on streamers and find their audience.

And you can mash them up with every other genre and create something new and exciting.

Mash-up Potential for the Horror Genre

Some subgenres of horror film include comedy horror, folk horror, body horror, found footage, holiday horror, psychological horror, science fiction horror, slasher, supernatural horror, Gothic horror, natural horror, zombie horror, and teen horror.

These all open you up to mashing up other genres with horror. Creative mixes help capture the horror audience and put a spin on the tropes.

Think about movies like The Mummy , which adds adventure. Or even something like Shaun of the Dead , which adds comedy.

Or what about a show like Dexter ? Police procedural meets serial killer.

Summing up the Horror Genre in Movies and TV

It's hard to look at a genre like this and not feel the awe of human terror. We have so many things we are afraid of, and we put them all out into the open for audiences to relate to. Horror is evolving as more and more people get voices.

We read and see new stories every day. Horror is one of our most interesting genres because it continues to change with the times. It's always in flux, and it's always going to be with us.

From the works of Jordan Peele to a movie like Promising Young Woman , horror allows you to get something off your chest and find audiences who relate. So what do you have to say? And can you say it with blood spatter?

Horror might be for you.

What's next? Learn every film genre !

Film and TV genres affect who watches your work, how it's classified, and even how it's reviewed. So how do you decide what you're writing? And which genres to mash-up? The secret is in the tropes.

Click the link to learn more!

Dig this spooky post? Then check out the rest of our Horror Week coverage for more tips, tricks, and terrifying takes.

- What Does the Horror Genre Mean to Two Legendary Horror Masters? ›

- What Is the Cosmic Horror Genre in Film and TV? (Definitions and Examples) ›

- The Ultimate Guide to Horror Subgenres ›

- Genre type list ›

- What Is the First Horror Film? | No Film School ›

- About - What is Horror? - LibGuides at The Westport Library ›

- What Is Horror Fiction? Learn About the Horror Genre, Plus 7 ... ›

- Horror film - Wikipedia ›

How the NO FAKES Act is a Bipartisan Challenge To AI

Attorney douglas mirell breaks down the promising new legislation combatting the unethical use of ai..

By Douglas Mirell, Partner at Greenberg Glusker

It is an extraordinarily rare day when Democrats and Republicans in the United State Senate can agree upon anything. But July 31, 2024 was just such a day.

On that date, two Democrats (Chris Coons, Delaware and Amy Klobuchar, Minnesota) joined two Republicans (Marsha Blackburn, Tennessee and Thom Tillis, North Carolina) to introduce the Nurture Originals, Foster Art, and Keep Entertainment Safe Act of 2024 (known colloquially as the “NO FAKES Act”)—a measure designed to protect the voice and visual likeness of all individuals from unauthorized AI-generated recreations .

Beginning in October 2023, these four Senators and their staffs spent countless hours working with numerous stakeholders to craft legislation that seeks to prevent individuals and companies from producing unauthorized digital replicas, while simultaneously holding social media and other sites liable for hosting such replicas if those platforms fail to remove or disable that content in a timely manner.

Nearly as unprecedented as the bipartisan co-authorship of this bill was the coalition of frequently adversarial organizations that endorsed the NO FAKES Act . Among these groups was not only the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA), the Recording Industry Association of America, and the Recording Academy, but also the Motion Picture Association, Warner Music Group, and Universal Music Group. Other endorsers included Open AI, IBM, William Morris Endeavor, and Creative Artists Agency.

Key to the formation of this coalition was a set of exclusions that seek to safeguard First Amendment interests by, for example, exempting digital replicas that are “produced or used consistent with the public interest in bona fide commentary, criticism, scholarship, satire, or parody.”

Also exempted are “fleeting or negligible” usages, as well as a Forrest Gump -inspired exception that applies to documentary-style usages so long as the use of the digital replica does not create a “false impression that the work is ... [one] in which the individual participated.” In addition, advertisements and commercial announcements for such excluded uses are permissible, but only if the digital replica is “relevant to the subject of the work so advertised or announced.”

Notwithstanding the exceptional importance, and attendant dangers, of artificial intelligence to the entertainment community, the NO FAKES Act is not limited to protecting the rights of actors and recording artists. So long as what is being exploited is “the voice or visual likeness of an individual”—whether living or dead—the NO FAKES Act provides protection against unauthorized AI exploitation for all human beings, including minors.

Liability extends to two general categories of misconduct:

- The unauthorized production of a digital replica

- The unauthorized publication, reproduction, distribution, and transmission of a digital replica.

In the event of a violation, a civil lawsuit against individuals and online services can result in the imposition of damages of $5,000 per work, or $25,000 per work in the case of an entity other than an online service.

Alternatively, actual damages are available to the injured party, “plus any profits from the unauthorized use that are attributable to such use and are not taken into account in computing the actual damages.” Injunctive and other equitable relief is also available, as is an award of reasonable attorney’s fees to a prevailing plaintiff in the event of willful misconduct.

Finally, among the most significant aspects of the NO FAKES Act is its declaration that the rights it defines constitute “a law pertaining to intellectual property.” The ramifications of this characterization are profound. For nearly 30 years, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act has effectively given blanket immunity to platforms that host user-generated content. This means that websites and social media sites have no legal obligation to respond to demands that defamatory and other offensive content created by such users be removed or disabled. But, under that same Section 230, this immunity dissolves in the face of any intellectual property law.

The trade-off for this major concession is that platforms can still receive protection for the third-party content they post if they abide by a notice-and-takedown regime akin to that which has worked reasonably well with copyright infringement claims brought under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act.

While it is perhaps an understatement to suggest that the U.S. Congress does not typically move with alacrity when confronted with legislation addressing new technologies, the bipartisan recognition of the manifest threat posed by generative artificial intelligence may yet prove to be a notable exception to this traditional paradigm.

Douglas Mirell has consulted with SAG-AFTRA on “deepfake” and other artificial intelligence issues affecting the entertainment community. Most recently, Mr. Mirell strategized with SAG-AFTRA about the conversations it was having with various stakeholders beginning in October 2023 that led to the introduction of the NO FAKES Act.

Blackmagic Camera App Set to Finally Come to Android

What are the best mystery movies of all time, 'prometheus' explained—what did the movie mean and who are the engineers, turn your smartphone into an ai-powered micro-four-thirds camera, what are the best experimental films of all time, how composer ryan shore brought the "east meets west" concept to the big screen, control your lights wirelessly with amaran’s intuitive new app, 'alien: romulus' ending explained, who wrote 'interstellar', breaking down sex scenes in film and tv.

- About / FAQ

- Submit News

- Upcoming Horror

- Marketing Macabre

Horror News | HNN Official Site | Horror Movies,Trailers, Reviews

How to write an essay about horror movies.

Adrian Halen 06/26/2024 Articles special , Exclusive Articles

Horror movies have long been a popular genre in the film industry, thanks to those pulse-quickening thrill rides featuring heart-stopping moments of terror and suspense. Whether you’re a film student, a horror fan or just someone who has long been curious about the genre’s cultural significance, there’s no better way to hone that hankering for horror than to write an essay about the subject. If you need assistance, services like Academized writing service can help write my paper in a week , offering expert guidance and support in crafting essays on various topics, including horror movies.

1. Understanding the Genre

First, there are (literally) countless subgenres of horror movies, and to write about all of them as if they were basically the same thing would be a terrible read. You need to get a handle on the stereotypes: there are countless readers who might recognise you as a timid young woman when you look a lot more like an authoritative priest in their brain.

- Identify Subgenres: Although it is a diverse category, horror is not a genre unto itself but rather a domain that hosts a surprising amount of variety, with subgenres such as: supernatural horror (eg, The Exorcist); psychological horror (eg, Psycho); slasher horror (eg, Halloween); and more. Within these, different techniques produce different kinds of fear and suspense.

- Lesson (theme/subject): horror films elaborate a lot of Universal Ideas, some of which at the very root of human nature and explain things like fears of the unknown, driving instincts that test our core survival, meddlesome human curiosity and its catastrophic consequences. For instance, even though Jaws is about a fully grown, nearly indestructible shark that goes on rampage, it’s actually primarily about primal fears of nature and all the other things that lie just beyond our field of vision.

- Cultural Importance: Viewing horror films through a cultural lens shows how they reflect and address our cultural anxieties; for example, the zombie movie has been read as a metaphor for social problems, from consumerism (Dawn of the Dead) to pandemic (28 Days Later).

2. Analysing Techniques with Examples

Many films use horror as a setting or backdrop to their story, but a truly effective horror film subverts our expectations by using a range of audiovisual strategies to elicit fear and suspense from the viewer. By analysing films in detail, and understanding how they might create an atmosphere of dread, we can add depth and sophistication to our analysis of horror. For those seeking guidance, utilising the expertise of the best essay service can provide invaluable support in crafting insightful essays that delve into the intricacies of horror cinema.

- Use of Sound: Sound and score are crucial to bis, as are manipulations of sound (such as silence and sudden noises) that leave an audience tense and on edge. See how they use these tactics in A Quiet Place.

- The visual imagery: Whether in cinematography or visual effects – can also be hugely instrumental in generating responses. For example, the utilisation of poor lighting and shadows in The Babadook can lead viewers to feel disconcerted and afraid.

- Characterisation: Character, particularly antagonists, is vital in horror. Explore how iconic evil characters such as Freddy Krueger (A Nightmare on Elm Street) or Leatherface (The Texas Chain Saw Massacre) represent pure misgivings and become long term symbols of terror.

3. Constructing a Strong Thesis Statement

A strong thesis statement represents the heart and soul of your essay, summing up its main argument or interpretation:

Thesis Development: Choose a specific claim about the horror film you’re writing about and state it as a thesis; it should then help to determine the shape your essay will take. For example, ‘Supernatural forces in the film The Conjuring series function as a figurative way of depicting the vulnerability of family bonds to harmful influences from beyond the home.

4. Comparative Analysis

Analysis of horror movies can be improved by better drawing out contrasts between them. It can be quite helpful to write an essay drawing out similarities and differences between two movies, well-presented in a comparative table:

| Psychological | Isolation, Madness | Visually striking, surreal | |

| Found Footage | Haunting, Supernatural | Minimalist, tension-building | |

| Slasher | Meta-horror, Identity | Satirical, self-aware |

Setting these next to each other allows you to show how different horror directors treat the genre, and also what makes each film emotionally resonant with viewers.

5. Incorporating Critical Perspectives

To establish your essay, introduce what film critics and scholars who have written extensively about horror cinema have stated:

Critical Reviews: Look for reviews of a particular film studied by reliable or credible sources. These may present alternative perspectives, enabling you to see films through different lenses. Disclaimer: All Boris Karloff clips on our website are taken from the DVDs History’s Greatest Villains Boris Karloff and Universal’s Classic Monsters Complete 30-Film Collection, released by Shout! Factory.

Academic Analysis: Read textbook articles or chapters that analyse horror cinema in theoretical terms (psychoanalysis, feminist theory, cultural studies, etc) in order to understand how the movies are intended to communicate more ‘serious’ (or, given one’s acquaintance with other theoretical frameworks, perhaps ‘just as serious’) meanings and affective ‘lessons’.

6. Applying Theoretical Frameworks

To take a step further, try using theoretical tools that shed light on the wider themes present within horror cinema: theology/religion; psychoanalysis; queer theory; feminist theory/psychoanalysis.

- Final Girl Theory: Dubbed by American film scholar Carol J Clover, this theory investigates how films such as Halloween (1978) perpetuate the trope of the ‘final girl’ – often a sole female survivor in slasher films who triumphs over the killer – by reversing genre conventions. These conventions privilege male perspectives as the norm and relegate women to symbolism, as one of the ‘screaming girls’. Discuss how the representation of the final girl subverts or reinforces traditional gender roles.

In writing this essay, you would need to account for themes and techniques that drive the genre, as well as understand the cultural contexts that facilitate its development as a cinematic genre with subgenres of its own. By engaging with those requirements, your essay would utilise the appreciation and analysis of relevant cinematic techniques and develop a focused thesis. You might present a comparative analysis of horror genres, critically engage with a horror trope, or fully address a theoretical perspective on horror.

Related Articles

The Intersection of Online Casinos and Horror Movies: A Spine-Chilling Fusion

The Sinister Side of Entertainment: Horror Movies and the Critique of Online Casino Games

The Thrills of Fear and Fortune: Exploring the Intersection of Horror Movies and Casino Games

The Evolution of Horror Movies: From Classic Scares to Modern Terror

The Chilling Connection: Horror Movies and Blackjack

The Best 6 Horror-Themed Online Casino Games

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

(Why) Do You Like Scary Movies? A Review of the Empirical Research on Psychological Responses to Horror Films

Why do we watch and like horror films? Despite a century of horror film making and entertainment, little research has examined the human motivation to watch fictional horror and how horror film influences individuals’ behavioral, cognitive, and emotional responses. This review provides the first synthesis of the empirical literature on the psychology of horror film using multi-disciplinary research from psychology, psychotherapy, communication studies, development studies, clinical psychology, and media studies. The paper considers the motivations for people’s decision to watch horror, why people enjoy horror, how individual differences influence responses to, and preference for, horror film, how exposure to horror film changes behavior, how horror film is designed to achieve its effects, why we fear and why we fear specific classes of stimuli, and how liking for horror develops during childhood and adolescence. The literature suggests that (1) low empathy and fearfulness are associated with more enjoyment and desire to watch horror film but that specific dimensions of empathy are better predictors of people’s responses than are others; (2) there is a positive relationship between sensation-seeking and horror enjoyment/preference, but this relationship is not consistent; (3) men and boys prefer to watch, enjoy, and seek our horror more than do women and girls; (4) women are more prone to disgust sensitivity or anxiety than are men, and this may mediate the sex difference in the enjoyment of horror; (5) younger children are afraid of symbolic stimuli, whereas older children become afraid of concrete or realistic stimuli; and (6) in terms of coping with horror, physical coping strategies are more successful in younger children; priming with information about the feared object reduces fear and increases children’s enjoyment of frightening television and film. A number of limitations in the literature is identified, including the multifarious range of horror stimuli used in studies, disparities in methods, small sample sizes, and a lack of research on cross-cultural differences and similarities. Ideas for future research are explored.

Horror: An Introduction

“It seems an unaccountable pleasure which the spectators of a well-written tragedy receive from sorrow, terror, anxiety and other passions, that are in themselves disagreeable and uneasy” ( Hume, 1907 ).

Why do people watch, and enjoy watching, horror films, and why is this an important or useful question to ask? The primary aims of the horror film are to frighten, shock, horrify, and disgust using a variety of visual and auditory leitmotifs and devices including reference to the supernatural, the abnormal, to mutilation, blood, gore, the infliction of pain, death, deformity, putrefaction, darkness, invasion, mutation, extreme instability, and the unknown ( Cherry, 2009 ; Newman, 2011 ). It is the emphasis on these characteristics that tend to distinguish horror from the related genre of thriller or psychological thriller ( Hanich, 2011 ). Thrillers are designed to create suspense and terror, but the creation of these feelings is dependent not on the presence of mutilation, gore, or the supernatural but via more human devices. These boundaries, however, can be fuzzy. If these features are utilized in thrillers, they are not the principal focus of the film but are incidental to it (an example would be the ear-cutting scene in Reservoir Dogs, which is bloody and brutal but is contained within a film, which has a non-horror theme). Together with Westerns, science fiction, comedy, musicals, documentaries, and other film genres, which are characterized by particular tropes, styles, themes, characters, and visual leitmotifs, horror sets itself apart from other film types via its distinctive characteristics.