18 Qualitative Research Examples

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

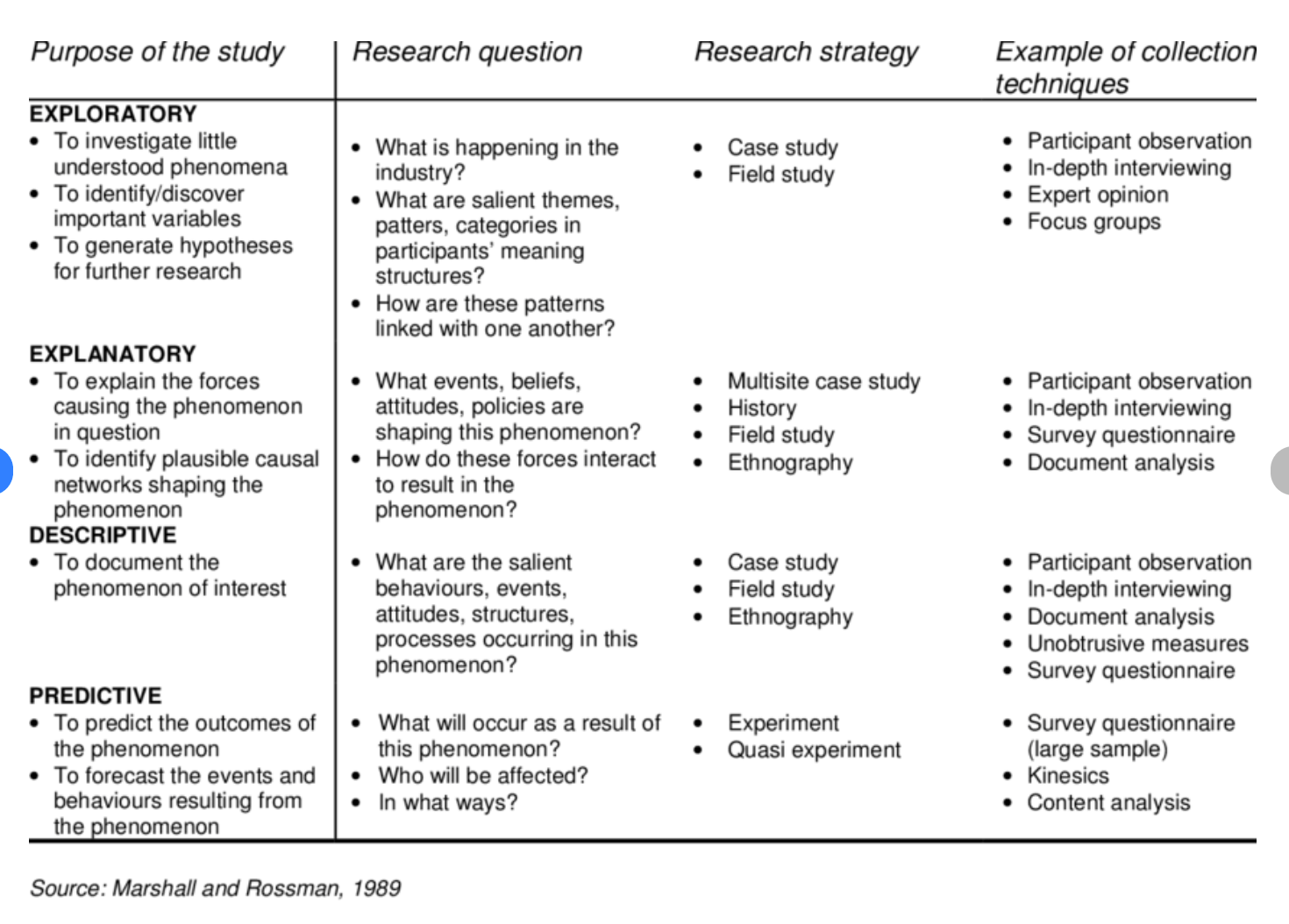

Qualitative research is an approach to scientific research that involves using observation to gather and analyze non-numerical, in-depth, and well-contextualized datasets.

It serves as an integral part of academic, professional, and even daily decision-making processes (Baxter & Jack, 2008).

Methods of qualitative research encompass a wide range of techniques, from in-depth personal encounters, like ethnographies (studying cultures in-depth) and autoethnographies (examining one’s own cultural experiences), to collection of diverse perspectives on topics through methods like interviewing focus groups (gatherings of individuals to discuss specific topics).

Qualitative Research Examples

1. ethnography.

Definition: Ethnography is a qualitative research design aimed at exploring cultural phenomena. Rooted in the discipline of anthropology , this research approach investigates the social interactions, behaviors, and perceptions within groups, communities, or organizations.

Ethnographic research is characterized by extended observation of the group, often through direct participation, in the participants’ environment. An ethnographer typically lives with the study group for extended periods, intricately observing their everyday lives (Khan, 2014).

It aims to present a complete, detailed and accurate picture of the observed social life, rituals, symbols, and values from the perspective of the study group.

| The key advantage of ethnography is its depth; it provides an in-depth understanding of the group’s behaviour, lifestyle, culture, and context. It also allows for flexibility, as researchers can adapt their approach based on their observations (Bryman, 2015) | There are issues regarding the subjective interpretation of data, and it’s time-consuming. It also requires the researchers to immerse themselves in the study environment, which might not always be feasible. |

Example of Ethnographic Research

Title: “ The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity “

Citation: Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Overview: This study by Evans (2010) provides a rich narrative of young adult male identity as experienced in everyday life. The author immersed himself among a group of young men, participating in their activities and cultivating a deep understanding of their lifestyle, values, and motivations. This research exemplified the ethnographic approach, revealing complexities of the subjects’ identities and societal roles, which could hardly be accessed through other qualitative research designs.

Read my Full Guide on Ethnography Here

2. Autoethnography

Definition: Autoethnography is an approach to qualitative research where the researcher uses their own personal experiences to extend the understanding of a certain group, culture, or setting. Essentially, it allows for the exploration of self within the context of social phenomena.

Unlike traditional ethnography, which focuses on the study of others, autoethnography turns the ethnographic gaze inward, allowing the researcher to use their personal experiences within a culture as rich qualitative data (Durham, 2019).

The objective is to critically appraise one’s personal experiences as they navigate and negotiate cultural, political, and social meanings. The researcher becomes both the observer and the participant, intertwining personal and cultural experiences in the research.

| One of the chief benefits of autoethnography is its ability to bridge the gap between researchers and audiences by using relatable experiences. It can also provide unique and profound insights unaccessible through traditional ethnographic approaches (Heinonen, 2012). | The subjective nature of this method can introduce bias. Critics also argue that the singular focus on personal experience may limit the contributions to broader cultural or social understanding. |

Example of Autoethnographic Research

Title: “ A Day In The Life Of An NHS Nurse “

Citation: Osben, J. (2019). A day in the life of a NHS nurse in 21st Century Britain: An auto-ethnography. The Journal of Autoethnography for Health & Social Care. 1(1).

Overview: This study presents an autoethnography of a day in the life of an NHS nurse (who, of course, is also the researcher). The author uses the research to achieve reflexivity, with the researcher concluding: “Scrutinising my practice and situating it within a wider contextual backdrop has compelled me to significantly increase my level of scrutiny into the driving forces that influence my practice.”

Read my Full Guide on Autoethnography Here

3. Semi-Structured Interviews

Definition: Semi-structured interviews stand as one of the most frequently used methods in qualitative research. These interviews are planned and utilize a set of pre-established questions, but also allow for the interviewer to steer the conversation in other directions based on the responses given by the interviewee.

In semi-structured interviews, the interviewer prepares a guide that outlines the focal points of the discussion. However, the interview is flexible, allowing for more in-depth probing if the interviewer deems it necessary (Qu, & Dumay, 2011). This style of interviewing strikes a balance between structured ones which might limit the discussion, and unstructured ones, which could lack focus.

| The main advantage of semi-structured interviews is their flexibility, allowing for exploration of unexpected topics that arise during the interview. It also facilitates the collection of robust, detailed data from participants’ perspectives (Smith, 2015). | Potential downsides include the possibility of data overload, periodic difficulties in analysis due to varied responses, and the fact they are time-consuming to conduct and analyze. |

Example of Semi-Structured Interview Research

Title: “ Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review “

Citation: Puts, M., et al. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Overview: Puts et al. (2014) executed an extensive systematic review in which they conducted semi-structured interviews with older adults suffering from cancer to examine the factors influencing their adherence to cancer treatment. The findings suggested that various factors, including side effects, faith in healthcare professionals, and social support have substantial impacts on treatment adherence. This research demonstrates how semi-structured interviews can provide rich and profound insights into the subjective experiences of patients.

4. Focus Groups

Definition: Focus groups are a qualitative research method that involves organized discussion with a selected group of individuals to gain their perspectives on a specific concept, product, or phenomenon. Typically, these discussions are guided by a moderator.

During a focus group session, the moderator has a list of questions or topics to discuss, and participants are encouraged to interact with each other (Morgan, 2010). This interactivity can stimulate more information and provide a broader understanding of the issue under scrutiny. The open format allows participants to ask questions and respond freely, offering invaluable insights into attitudes, experiences, and group norms.

| One of the key advantages of focus groups is their ability to deliver a rich understanding of participants’ experiences and beliefs. They can be particularly beneficial in providing a diverse range of perspectives and opening up new areas for exploration (Doody, Slevin, & Taggart, 2013). | Potential disadvantages include possible domination by a single participant, groupthink, or issues with confidentiality. Additionally, the results are not easily generalizable to a larger population due to the small sample size. |

Example of Focus Group Research

Title: “ Perspectives of Older Adults on Aging Well: A Focus Group Study “

Citation: Halaweh, H., Dahlin-Ivanoff, S., Svantesson, U., & Willén, C. (2018). Perspectives of older adults on aging well: a focus group study. Journal of aging research .

Overview: This study aimed to explore what older adults (aged 60 years and older) perceived to be ‘aging well’. The researchers identified three major themes from their focus group interviews: a sense of well-being, having good physical health, and preserving good mental health. The findings highlight the importance of factors such as positive emotions, social engagement, physical activity, healthy eating habits, and maintaining independence in promoting aging well among older adults.

5. Phenomenology

Definition: Phenomenology, a qualitative research method, involves the examination of lived experiences to gain an in-depth understanding of the essence or underlying meanings of a phenomenon.

The focus of phenomenology lies in meticulously describing participants’ conscious experiences related to the chosen phenomenon (Padilla-Díaz, 2015).

In a phenomenological study, the researcher collects detailed, first-hand perspectives of the participants, typically via in-depth interviews, and then uses various strategies to interpret and structure these experiences, ultimately revealing essential themes (Creswell, 2013). This approach focuses on the perspective of individuals experiencing the phenomenon, seeking to explore, clarify, and understand the meanings they attach to those experiences.

| An advantage of phenomenology is its potential to reveal rich, complex, and detailed understandings of human experiences in a way other research methods cannot. It encourages explorations of deep, often abstract or intangible aspects of human experiences (Bevan, 2014). | Phenomenology might be criticized for its subjectivity, the intense effort required during data collection and analysis, and difficulties in replicating the study. |

Example of Phenomenology Research

Title: “ A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: current state, promise, and future directions for research ”

Citation: Cilesiz, S. (2011). A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology: Current state, promise, and future directions for research. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59 , 487-510.

Overview: A phenomenological approach to experiences with technology by Sebnem Cilesiz represents a good starting point for formulating a phenomenological study. With its focus on the ‘essence of experience’, this piece presents methodological, reliability, validity, and data analysis techniques that phenomenologists use to explain how people experience technology in their everyday lives.

6. Grounded Theory

Definition: Grounded theory is a systematic methodology in qualitative research that typically applies inductive reasoning . The primary aim is to develop a theoretical explanation or framework for a process, action, or interaction grounded in, and arising from, empirical data (Birks & Mills, 2015).

In grounded theory, data collection and analysis work together in a recursive process. The researcher collects data, analyses it, and then collects more data based on the evolving understanding of the research context. This ongoing process continues until a comprehensive theory that represents the data and the associated phenomenon emerges – a point known as theoretical saturation (Charmaz, 2014).

| An advantage of grounded theory is its ability to generate a theory that is closely related to the reality of the persons involved. It permits flexibility and can facilitate a deep understanding of complex processes in their natural contexts (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). | Critics note that it can be a lengthy and complicated process; others critique the emphasis on theory development over descriptive detail. |

Example of Grounded Theory Research

Title: “ Student Engagement in High School Classrooms from the Perspective of Flow Theory “

Citation: Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158–176.

Overview: Shernoff and colleagues (2003) used grounded theory to explore student engagement in high school classrooms. The researchers collected data through student self-reports, interviews, and observations. Key findings revealed that academic challenge, student autonomy, and teacher support emerged as the most significant factors influencing students’ engagement, demonstrating how grounded theory can illuminate complex dynamics within real-world contexts.

7. Narrative Research

Definition: Narrative research is a qualitative research method dedicated to storytelling and understanding how individuals experience the world. It focuses on studying an individual’s life and experiences as narrated by that individual (Polkinghorne, 2013).

In narrative research, the researcher collects data through methods such as interviews, observations , and document analysis. The emphasis is on the stories told by participants – narratives that reflect their experiences, thoughts, and feelings.

These stories are then interpreted by the researcher, who attempts to understand the meaning the participant attributes to these experiences (Josselson, 2011).

| The strength of narrative research is its ability to provide a deep, holistic, and rich understanding of an individual’s experiences over time. It is well-suited to capturing the complexities and intricacies of human lives and their contexts (Leiblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, 2008). | Narrative research may be criticized for its highly interpretive nature, the potential challenges of ensuring reliability and validity, and the complexity of narrative analysis. |

Example of Narrative Research

Title: “Narrative Structures and the Language of the Self”

Citation: McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative . American Psychological Association.

Overview: In this innovative study, McAdams et al. (2006) employed narrative research to explore how individuals construct their identities through the stories they tell about themselves. By examining personal narratives, the researchers discerned patterns associated with characters, motivations, conflicts, and resolutions, contributing valuable insights about the relationship between narrative and individual identity.

8. Case Study Research

Definition: Case study research is a qualitative research method that involves an in-depth investigation of a single instance or event: a case. These ‘cases’ can range from individuals, groups, or entities to specific projects, programs, or strategies (Creswell, 2013).

The case study method typically uses multiple sources of information for comprehensive contextual analysis. It aims to explore and understand the complexity and uniqueness of a particular case in a real-world context (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). This investigation could result in a detailed description of the case, a process for its development, or an exploration of a related issue or problem.

| Case study research is ideal for a holistic, in-depth investigation, making complex phenomena understandable and allowing for the exploration of contexts and activities where it is not feasible to use other research methods (Crowe et al., 2011). | Critics of case study research often cite concerns about the representativeness of a single case, the limited ability to generalize findings, and potential bias in data collection and interpretation. |

Example of Case Study Research

Title: “ Teacher’s Role in Fostering Preschoolers’ Computational Thinking: An Exploratory Case Study “

Citation: Wang, X. C., Choi, Y., Benson, K., Eggleston, C., & Weber, D. (2021). Teacher’s role in fostering preschoolers’ computational thinking: An exploratory case study. Early Education and Development , 32 (1), 26-48.

Overview: This study investigates the role of teachers in promoting computational thinking skills in preschoolers. The study utilized a qualitative case study methodology to examine the computational thinking scaffolding strategies employed by a teacher interacting with three preschoolers in a small group setting. The findings highlight the importance of teachers’ guidance in fostering computational thinking practices such as problem reformulation/decomposition, systematic testing, and debugging.

Read about some Famous Case Studies in Psychology Here

9. Participant Observation

Definition: Participant observation has the researcher immerse themselves in a group or community setting to observe the behavior of its members. It is similar to ethnography, but generally, the researcher isn’t embedded for a long period of time.

The researcher, being a participant, engages in daily activities, interactions, and events as a way of conducting a detailed study of a particular social phenomenon (Kawulich, 2005).

The method involves long-term engagement in the field, maintaining detailed records of observed events, informal interviews, direct participation, and reflexivity. This approach allows for a holistic view of the participants’ lived experiences, behaviours, and interactions within their everyday environment (Dewalt, 2011).

| A key strength of participant observation is its capacity to offer intimate, nuanced insights into social realities and practices directly from the field. It allows for broader context understanding, emotional insights, and a constant iterative process (Mulhall, 2003). | The method may present challenges including potential observer bias, the difficulty in ensuring ethical standards, and the risk of ‘going native’, where the boundary between being a participant and researcher blurs. |

Example of Participant Observation Research

Title: Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics

Citation: Heemskerk, E. M., Heemskerk, K., & Wats, M. M. (2017). Conflict in the boardroom: a participant observation study of supervisory board dynamics. Journal of Management & Governance , 21 , 233-263.

Overview: This study examined how conflicts within corporate boards affect their performance. The researchers used a participant observation method, where they actively engaged with 11 supervisory boards and observed their dynamics. They found that having a shared understanding of the board’s role called a common framework, improved performance by reducing relationship conflicts, encouraging task conflicts, and minimizing conflicts between the board and CEO.

10. Non-Participant Observation

Definition: Non-participant observation is a qualitative research method in which the researcher observes the phenomena of interest without actively participating in the situation, setting, or community being studied.

This method allows the researcher to maintain a position of distance, as they are solely an observer and not a participant in the activities being observed (Kawulich, 2005).

During non-participant observation, the researcher typically records field notes on the actions, interactions, and behaviors observed , focusing on specific aspects of the situation deemed relevant to the research question.

This could include verbal and nonverbal communication , activities, interactions, and environmental contexts (Angrosino, 2007). They could also use video or audio recordings or other methods to collect data.

| Non-participant observation can increase distance from the participants and decrease researcher bias, as the observer does not become involved in the community or situation under study (Jorgensen, 2015). This method allows for a more detached and impartial view of practices, behaviors, and interactions. | Criticisms of this method include potential observer effects, where individuals may change their behavior if they know they are being observed, and limited contextual understanding, as observers do not participate in the setting’s activities. |

Example of Non-Participant Observation Research

Title: Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non-participant observation study

Citation: Sreeram, A., Cross, W. M., & Townsin, L. (2023). Mental Health Nurses’ attitudes towards mental illness and recovery‐oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units: A non‐participant observation study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing .

Overview: This study investigated the attitudes of mental health nurses towards mental illness and recovery-oriented practice in acute inpatient psychiatric units. The researchers used a non-participant observation method, meaning they observed the nurses without directly participating in their activities. The findings shed light on the nurses’ perspectives and behaviors, providing valuable insights into their attitudes toward mental health and recovery-focused care in these settings.

11. Content Analysis

Definition: Content Analysis involves scrutinizing textual, visual, or spoken content to categorize and quantify information. The goal is to identify patterns, themes, biases, or other characteristics (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005).

Content Analysis is widely used in various disciplines for a multitude of purposes. Researchers typically use this method to distill large amounts of unstructured data, like interview transcripts, newspaper articles, or social media posts, into manageable and meaningful chunks.

When wielded appropriately, Content Analysis can illuminate the density and frequency of certain themes within a dataset, provide insights into how specific terms or concepts are applied contextually, and offer inferences about the meanings of their content and use (Duriau, Reger, & Pfarrer, 2007).

| The application of Content Analysis offers several strengths, chief among them being the ability to gain an in-depth, contextualized, understanding of a range of texts – both written and multimodal (Gray, Grove, & Sutherland, 2017) – see also: . | Content analysis is dependent on the descriptors that the researcher selects to examine the data, potentially leading to bias. Moreover, this method may also lose sight of the wider social context, which can limit the depth of the analysis (Krippendorff, 2013). |

Example of Content Analysis

Title: Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news .

Citation: Semetko, H. A., & Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing European politics: A content analysis of press and television news. Journal of Communication, 50 (2), 93-109.

Overview: This study analyzed press and television news articles about European politics using a method called content analysis. The researchers examined the prevalence of different “frames” in the news, which are ways of presenting information to shape audience perceptions. They found that the most common frames were attribution of responsibility, conflict, economic consequences, human interest, and morality.

Read my Full Guide on Content Analysis Here

12. Discourse Analysis

Definition: Discourse Analysis, a qualitative research method, interprets the meanings, functions, and coherence of certain languages in context.

Discourse analysis is typically understood through social constructionism, critical theory , and poststructuralism and used for understanding how language constructs social concepts (Cheek, 2004).

Discourse Analysis offers great breadth, providing tools to examine spoken or written language, often beyond the level of the sentence. It enables researchers to scrutinize how text and talk articulate social and political interactions and hierarchies.

Insight can be garnered from different conversations, institutional text, and media coverage to understand how topics are addressed or framed within a specific social context (Jorgensen & Phillips, 2002).

| Discourse Analysis presents as its strength the ability to explore the intricate relationship between language and society. It goes beyond mere interpretation of content and scrutinizes the power dynamics underlying discourse. Furthermore, it can also be beneficial in discovering hidden meanings and uncovering marginalized voices (Wodak & Meyer, 2015). | Despite its strengths, Discourse Analysis possesses specific weaknesses. This approach may be open to allegations of subjectivity due to its interpretive nature. Furthermore, it can be quite time-consuming and requires the researcher to be familiar with a wide variety of theoretical and analytical frameworks (Parker, 2014). |

Example of Discourse Analysis

Title: The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis

Citation: Thomas, S. (2005). The construction of teacher identities in educational policy documents: A critical discourse analysis. Critical Studies in Education, 46 (2), 25-44.

Overview: The author examines how an education policy in one state of Australia positions teacher professionalism and teacher identities. While there are competing discourses about professional identity, the policy framework privileges a narrative that frames the ‘good’ teacher as one that accepts ever-tightening control and regulation over their professional practice.

Read my Full Guide on Discourse Analysis Here

13. Action Research

Definition: Action Research is a qualitative research technique that is employed to bring about change while simultaneously studying the process and results of that change.

This method involves a cyclical process of fact-finding, action, evaluation, and reflection (Greenwood & Levin, 2016).

Typically, Action Research is used in the fields of education, social sciences , and community development. The process isn’t just about resolving an issue but also developing knowledge that can be used in the future to address similar or related problems.

The researcher plays an active role in the research process, which is normally broken down into four steps:

- developing a plan to improve what is currently being done

- implementing the plan

- observing the effects of the plan, and

- reflecting upon these effects (Smith, 2010).

| Action Research has the immense strength of enabling practitioners to address complex situations in their professional context. By fostering reflective practice, it ignites individual and organizational learning. Furthermore, it provides a robust way to bridge the theory-practice divide and can lead to the development of best practices (Zuber-Skerritt, 2019). | Action Research requires a substantial commitment of time and effort. Also, the participatory nature of this research can potentially introduce bias, and its iterative nature can blur the line between where the research process ends and where the implementation begins (Koshy, Koshy, & Waterman, 2010). |

Example of Action Research

Title: Using Digital Sandbox Gaming to Improve Creativity Within Boys’ Writing

Citation: Ellison, M., & Drew, C. (2020). Using digital sandbox gaming to improve creativity within boys’ writing. Journal of Research in Childhood Education , 34 (2), 277-287.

Overview: This was a research study one of my research students completed in his own classroom under my supervision. He implemented a digital game-based approach to literacy teaching with boys and interviewed his students to see if the use of games as stimuli for storytelling helped draw them into the learning experience.

Read my Full Guide on Action Research Here

14. Semiotic Analysis

Definition: Semiotic Analysis is a qualitative method of research that interprets signs and symbols in communication to understand sociocultural phenomena. It stems from semiotics, the study of signs and symbols and their use or interpretation (Chandler, 2017).

In a Semiotic Analysis, signs (anything that represents something else) are interpreted based on their significance and the role they play in representing ideas.

This type of research often involves the examination of images, sounds, and word choice to uncover the embedded sociocultural meanings. For example, an advertisement for a car might be studied to learn more about societal views on masculinity or success (Berger, 2010).

| The prime strength of the Semiotic Analysis lies in its ability to reveal the underlying ideologies within cultural symbols and messages. It helps to break down complex phenomena into manageable signs, yielding powerful insights about societal values, identities, and structures (Mick, 1986). | On the downside, because Semiotic Analysis is primarily interpretive, its findings may heavily rely on the particular theoretical lens and personal bias of the researcher. The ontology of signs and meanings can also be inherently subject to change, in the analysis (Lannon & Cooper, 2012). |

Example of Semiotic Research

Title: Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia

Citation: Symes, C. (2023). Shielding the learned body: a semiotic analysis of school badges in New South Wales, Australia. Semiotica , 2023 (250), 167-190.

Overview: This study examines school badges in New South Wales, Australia, and explores their significance through a semiotic analysis. The badges, which are part of the school’s visual identity, are seen as symbolic representations that convey meanings. The analysis reveals that these badges often draw on heraldic models, incorporating elements like colors, names, motifs, and mottoes that reflect local culture and history, thus connecting students to their national identity. Additionally, the study highlights how some schools have shifted from traditional badges to modern logos and slogans, reflecting a more business-oriented approach.

15. Qualitative Longitudinal Studies

Definition: Qualitative Longitudinal Studies are a research method that involves repeated observation of the same items over an extended period of time.

Unlike a snapshot perspective, this method aims to piece together individual histories and examine the influences and impacts of change (Neale, 2019).

Qualitative Longitudinal Studies provide an in-depth understanding of change as it happens, including changes in people’s lives, their perceptions, and their behaviors.

For instance, this method could be used to follow a group of students through their schooling years to understand the evolution of their learning behaviors and attitudes towards education (Saldaña, 2003).

| One key strength of Qualitative Longitudinal Studies is its ability to capture change and continuity over time. It allows for an in-depth understanding of individuals or context evolution. Moreover, it provides unique insights into the temporal ordering of events and experiences (Farrall, 2006). | Qualitative Longitudinal Studies come with their own share of weaknesses. Mainly, they require a considerable investment of time and resources. Moreover, they face the challenges of attrition (participants dropping out of the study) and repeated measures that may influence participants’ behaviors (Saldaña, 2014). |

Example of Qualitative Longitudinal Research

Title: Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study

Citation: Hackett, J., Godfrey, M., & Bennett, M. I. (2016). Patient and caregiver perspectives on managing pain in advanced cancer: a qualitative longitudinal study. Palliative medicine , 30 (8), 711-719.

Overview: This article examines how patients and their caregivers manage pain in advanced cancer through a qualitative longitudinal study. The researchers interviewed patients and caregivers at two different time points and collected audio diaries to gain insights into their experiences, making this study longitudinal.

Read my Full Guide on Longitudinal Research Here

16. Open-Ended Surveys

Definition: Open-Ended Surveys are a type of qualitative research method where respondents provide answers in their own words. Unlike closed-ended surveys, which limit responses to predefined options, open-ended surveys allow for expansive and unsolicited explanations (Fink, 2013).

Open-ended surveys are commonly used in a range of fields, from market research to social studies. As they don’t force respondents into predefined response categories, these surveys help to draw out rich, detailed data that might uncover new variables or ideas.

For example, an open-ended survey might be used to understand customer opinions about a new product or service (Lavrakas, 2008).

Contrast this to a quantitative closed-ended survey, like a Likert scale, which could theoretically help us to come up with generalizable data but is restricted by the questions on the questionnaire, meaning new and surprising data and insights can’t emerge from the survey results in the same way.

| The key advantage of Open-Ended Surveys is their ability to generate in-depth, nuanced data that allow for a rich, . They provide a more personalized response from participants, and they may uncover areas of investigation that the researchers did not previously consider (Sue & Ritter, 2012). | Open-Ended Surveys require significant time and effort to analyze due to the variability of responses. Furthermore, the results obtained from Open-Ended Surveys can be more susceptible to subjective interpretation and may lack statistical generalizability (Fielding & Fielding, 2008). |

Example of Open-Ended Survey Research

Title: Advantages and disadvantages of technology in relationships: Findings from an open-ended survey

Citation: Hertlein, K. M., & Ancheta, K. (2014). Advantages and disadvantages of technology in relationships: Findings from an open-ended survey. The Qualitative Report , 19 (11), 1-11.

Overview: This article examines the advantages and disadvantages of technology in couple relationships through an open-ended survey method. Researchers analyzed responses from 410 undergraduate students to understand how technology affects relationships. They found that technology can contribute to relationship development, management, and enhancement, but it can also create challenges such as distancing, lack of clarity, and impaired trust.

17. Naturalistic Observation

Definition: Naturalistic Observation is a type of qualitative research method that involves observing individuals in their natural environments without interference or manipulation by the researcher.

Naturalistic observation is often used when conducting research on behaviors that cannot be controlled or manipulated in a laboratory setting (Kawulich, 2005).

It is frequently used in the fields of psychology, sociology, and anthropology. For instance, to understand the social dynamics in a schoolyard, a researcher could spend time observing the children interact during their recess, noting their behaviors, interactions, and conflicts without imposing their presence on the children’s activities (Forsyth, 2010).

| The predominant strength of Naturalistic Observation lies in : it allows the behavior of interest to be studied in the conditions under which it normally occurs. This method can also lead to the discovery of new behavioral patterns or phenomena not previously revealed in experimental research (Barker, Pistrang, & Elliott, 2016). | The observer may have difficulty avoiding subjective interpretations and biases of observed behaviors. Additionally, it may be very time-consuming, and the presence of the observer, even if unobtrusive, may influence the behavior of those being observed (Rosenbaum, 2017). |

Example of Naturalistic Observation Research

Title: Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study

Citation: Kaplan, D. M., Raison, C. L., Milek, A., Tackman, A. M., Pace, T. W., & Mehl, M. R. (2018). Dispositional mindfulness in daily life: A naturalistic observation study. PloS one , 13 (11), e0206029.

Overview: In this study, researchers conducted two studies: one exploring assumptions about mindfulness and behavior, and the other using naturalistic observation to examine actual behavioral manifestations of mindfulness. They found that trait mindfulness is associated with a heightened perceptual focus in conversations, suggesting that being mindful is expressed primarily through sharpened attention rather than observable behavioral or social differences.

Read my Full Guide on Naturalistic Observation Here

18. Photo-Elicitation

Definition: Photo-elicitation utilizes photographs as a means to trigger discussions and evoke responses during interviews. This strategy aids in bringing out topics of discussion that may not emerge through verbal prompting alone (Harper, 2002).

Traditionally, Photo-Elicitation has been useful in various fields such as education, psychology, and sociology. The method involves the researcher or participants taking photographs, which are then used as prompts for discussion.

For instance, a researcher studying urban environmental issues might invite participants to photograph areas in their neighborhood that they perceive as environmentally detrimental, and then discuss each photo in depth (Clark-Ibáñez, 2004).

| Photo-Elicitation boasts of its ability to facilitate dialogue that may not arise through conventional interview methods. As a visual catalyst, it can support interviewees in articulating their experiences and emotions, potentially resulting in the generation of rich and insightful data (Heisley & Levy, 1991). | There are some limitations with Photo-Elicitation. Interpretation of the images can be highly subjective and might be influenced by cultural and personal variables. Additionally, ethical concerns may arise around privacy and consent, particularly when photographing individuals (Van Auken, Frisvoll, & Stewart, 2010). |

Example of Photo-Elicitation Research

Title: Early adolescent food routines: A photo-elicitation study

Citation: Green, E. M., Spivak, C., & Dollahite, J. S. (2021). Early adolescent food routines: A photo-elicitation study. Appetite, 158 .

Overview: This study focused on early adolescents (ages 10-14) and their food routines. Researchers conducted in-depth interviews using a photo-elicitation approach, where participants took photos related to their food choices and experiences. Through analysis, the study identified various routines and three main themes: family, settings, and meals/foods consumed, revealing how early adolescents view and are influenced by their eating routines.

Features of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a research method focused on understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013).

Some key features of this method include:

- Naturalistic Inquiry: Qualitative research happens in the natural setting of the phenomena, aiming to understand “real world” situations (Patton, 2015). This immersion in the field or subject allows the researcher to gather a deep understanding of the subject matter.

- Emphasis on Process: It aims to understand how events unfold over time rather than focusing solely on outcomes (Merriam & Tisdell, 2015). The process-oriented nature of qualitative research allows researchers to investigate sequences, timing, and changes.

- Interpretive: It involves interpreting and making sense of phenomena in terms of the meanings people assign to them (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). This interpretive element allows for rich, nuanced insights into human behavior and experiences.

- Holistic Perspective: Qualitative research seeks to understand the whole phenomenon rather than focusing on individual components (Creswell, 2013). It emphasizes the complex interplay of factors, providing a richer, more nuanced view of the research subject.

- Prioritizes Depth over Breadth: Qualitative research favors depth of understanding over breadth, typically involving a smaller but more focused sample size (Hennink, Hutter, & Bailey, 2020). This enables detailed exploration of the phenomena of interest, often leading to rich and complex data.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research

Qualitative research centers on exploring and understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013).

It involves an in-depth approach to the subject matter, aiming to capture the richness and complexity of human experience.

Examples include conducting interviews, observing behaviors, or analyzing text and images.

There are strengths inherent in this approach. In its focus on understanding subjective experiences and interpretations, qualitative research can yield rich and detailed data that quantitative research may overlook (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011).

Additionally, qualitative research is adaptive, allowing the researcher to respond to new directions and insights as they emerge during the research process.

However, there are also limitations. Because of the interpretive nature of this research, findings may not be generalizable to a broader population (Marshall & Rossman, 2014). Well-designed quantitative research, on the other hand, can be generalizable.

Moreover, the reliability and validity of qualitative data can be challenging to establish due to its subjective nature, unlike quantitative research, which is ideally more objective.

| Research method focused on understanding the meaning individuals or groups attribute to a social or human problem (Creswell, 2013) | Research method dealing with numbers and statistical analysis (Creswell & Creswell, 2017) | |

| Interviews, text/image analysis (Fugard & Potts, 2015) | Surveys, lab experiments (Van Voorhis & Morgan, 2007) | |

| Yields rich and detailed data; adaptive to new directions and insights (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011) | Enables precise measurement and analysis; findings can be generalizable; allows for replication (Ali & Bhaskar, 2016) | |

| Findings may not be generalizable; labor-intensive and time-consuming; reliability and validity can be challenging to establish (Marshall & Rossman, 2014) | May miss contextual detail; depends heavily on design and instrumentation; does not provide detailed description of behaviors, attitudes, and experiences (Mackey & Gass, 2015) |

Compare Qualitative and Quantitative Research Methodologies in This Guide Here

In conclusion, qualitative research methods provide distinctive ways to explore social phenomena and understand nuances that quantitative approaches might overlook. Each method, from Ethnography to Photo-Elicitation, presents its strengths and weaknesses but they all offer valuable means of investigating complex, real-world situations. The goal for the researcher is not to find a definitive tool, but to employ the method best suited for their research questions and the context at hand (Almalki, 2016). Above all, these methods underscore the richness of human experience and deepen our understanding of the world around us.

Angrosino, M. (2007). Doing ethnographic and observational research. Sage Publications.

Areni, C. S., & Kim, D. (1994). The influence of in-store lighting on consumers’ examination of merchandise in a wine store. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 11 (2), 117-125.

Barker, C., Pistrang, N., & Elliott, R. (2016). Research Methods in Clinical Psychology: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. John Wiley & Sons.

Baxter, P. & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13 (4), 544-559.

Berger, A. A. (2010). The Objects of Affection: Semiotics and Consumer Culture. Palgrave Macmillan.

Bevan, M. T. (2014). A method of phenomenological interviewing. Qualitative health research, 24 (1), 136-144.

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage Publications.

Bryman, A. (2015) . The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage Publications.

Chandler, D. (2017). Semiotics: The Basics. Routledge.

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage Publications.

Cheek, J. (2004). At the margins? Discourse analysis and qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 14(8), 1140-1150.

Clark-Ibáñez, M. (2004). Framing the social world with photo-elicitation interviews. American Behavioral Scientist, 47(12), 1507-1527.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A., & Sheikh, A. (2011). The case study approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(100), 1-9.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. Sage.

Dewalt, K. M., & Dewalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers. Rowman Altamira.

Doody, O., Slevin, E., & Taggart, L. (2013). Focus group interviews in nursing research: part 1. British Journal of Nursing, 22(1), 16-19.

Durham, A. (2019). Autoethnography. In P. Atkinson (Ed.), Qualitative Research Methods. Oxford University Press.

Duriau, V. J., Reger, R. K., & Pfarrer, M. D. (2007). A content analysis of the content analysis literature in organization studies: Research themes, data sources, and methodological refinements. Organizational Research Methods, 10(1), 5-34.

Evans, J. (2010). The Everyday Lives of Men: An Ethnographic Investigation of Young Adult Male Identity. Peter Lang.

Farrall, S. (2006). What is qualitative longitudinal research? Papers in Social Research Methods, Qualitative Series, No.11, London School of Economics, Methodology Institute.

Fielding, J., & Fielding, N. (2008). Synergy and synthesis: integrating qualitative and quantitative data. The SAGE handbook of social research methods, 555-571.

Fink, A. (2013). How to conduct surveys: A step-by-step guide . SAGE.

Forsyth, D. R. (2010). Group Dynamics . Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Fugard, A. J. B., & Potts, H. W. W. (2015). Supporting thinking on sample sizes for thematic analyses: A quantitative tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18 (6), 669–684.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter.

Gray, J. R., Grove, S. K., & Sutherland, S. (2017). Burns and Grove’s the Practice of Nursing Research E-Book: Appraisal, Synthesis, and Generation of Evidence. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Greenwood, D. J., & Levin, M. (2016). Introduction to action research: Social research for social change. SAGE.

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17 (1), 13-26.

Heinonen, T. (2012). Making Sense of the Social: Human Sciences and the Narrative Turn. Rozenberg Publishers.

Heisley, D. D., & Levy, S. J. (1991). Autodriving: A photoelicitation technique. Journal of Consumer Research, 18 (3), 257-272.

Hennink, M. M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2020). Qualitative Research Methods . SAGE Publications Ltd.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15 (9), 1277–1288.

Jorgensen, D. L. (2015). Participant Observation. In Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences: An Interdisciplinary, Searchable, and Linkable Resource. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Jorgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method . SAGE.

Josselson, R. (2011). Narrative research: Constructing, deconstructing, and reconstructing story. In Five ways of doing qualitative analysis . Guilford Press.

Kawulich, B. B. (2005). Participant observation as a data collection method. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 6 (2).

Khan, S. (2014). Qualitative Research Method: Grounded Theory. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy, 5 (4), 86-88.

Koshy, E., Koshy, V., & Waterman, H. (2010). Action Research in Healthcare . SAGE.

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. SAGE.

Lannon, J., & Cooper, P. (2012). Humanistic Advertising: A Holistic Cultural Perspective. International Journal of Advertising, 15 (2), 97–111.

Lavrakas, P. J. (2008). Encyclopedia of survey research methods. SAGE Publications.

Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (2008). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and interpretation. Sage Publications.

Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2015). Second language research: Methodology and design. Routledge.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2014). Designing qualitative research. Sage publications.

McAdams, D. P., Josselson, R., & Lieblich, A. (2006). Identity and story: Creating self in narrative. American Psychological Association.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Mick, D. G. (1986). Consumer Research and Semiotics: Exploring the Morphology of Signs, Symbols, and Significance. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (2), 196-213.

Morgan, D. L. (2010). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications.

Mulhall, A. (2003). In the field: notes on observation in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41 (3), 306-313.

Neale, B. (2019). What is Qualitative Longitudinal Research? Bloomsbury Publishing.

Nolan, L. B., & Renderos, T. B. (2012). A focus group study on the influence of fatalism and religiosity on cancer risk perceptions in rural, eastern North Carolina. Journal of religion and health, 51 (1), 91-104.

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in educational qualitative research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science? International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1 (2), 101-110.

Parker, I. (2014). Discourse dynamics: Critical analysis for social and individual psychology . Routledge.

Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage Publications.

Polkinghorne, D. E. (2013). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. In Life history and narrative. Routledge.

Puts, M. T., Tapscott, B., Fitch, M., Howell, D., Monette, J., Wan-Chow-Wah, D., Krzyzanowska, M., Leighl, N. B., Springall, E., & Alibhai, S. (2014). Factors influencing adherence to cancer treatment in older adults with cancer: a systematic review. Annals of oncology, 25 (3), 564-577.

Qu, S. Q., & Dumay, J. (2011). The qualitative research interview . Qualitative research in accounting & management.

Ali, J., & Bhaskar, S. B. (2016). Basic statistical tools in research and data analysis. Indian Journal of Anaesthesia, 60 (9), 662–669.

Rosenbaum, M. S. (2017). Exploring the social supportive role of third places in consumers’ lives. Journal of Service Research, 20 (1), 26-42.

Saldaña, J. (2003). Longitudinal Qualitative Research: Analyzing Change Through Time . AltaMira Press.

Saldaña, J. (2014). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. SAGE.

Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Shneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2003). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. School Psychology Quarterly, 18 (2), 158-176.

Smith, J. A. (2015). Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods . Sage Publications.

Smith, M. K. (2010). Action Research. The encyclopedia of informal education.

Sue, V. M., & Ritter, L. A. (2012). Conducting online surveys . SAGE Publications.

Van Auken, P. M., Frisvoll, S. J., & Stewart, S. I. (2010). Visualising community: using participant-driven photo-elicitation for research and application. Local Environment, 15 (4), 373-388.

Van Voorhis, F. L., & Morgan, B. L. (2007). Understanding Power and Rules of Thumb for Determining Sample Sizes. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 3 (2), 43–50.

Wodak, R., & Meyer, M. (2015). Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis . SAGE.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (2018). Action research for developing educational theories and practices . Routledge.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 19 Top Cognitive Psychology Theories (Explained)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 119 Bloom’s Taxonomy Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ All 6 Levels of Understanding (on Bloom’s Taxonomy)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 15 Self-Actualization Examples (Maslow's Hierarchy)

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite or clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduce the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Place the topic into a particular context that defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provide the framework for reporting the results and indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, and understood],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE: A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where gaps exist in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people]. Also, authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features:

1. Compelling Topic The problem chosen should be one that motivates you to address it but simple curiosity is not a good enough reason to pursue a research study because this does not indicate significance. The problem that you choose to explore must be important to you, but it must also be viewed as important by your readers and to a the larger academic and/or social community that could be impacted by the results of your study. 2. Supports Multiple Perspectives The problem must be phrased in a way that avoids dichotomies and instead supports the generation and exploration of multiple perspectives. A general rule of thumb in the social sciences is that a good research problem is one that would generate a variety of viewpoints from a composite audience made up of reasonable people. 3. Researchability This isn't a real word but it represents an important aspect of creating a good research statement. It seems a bit obvious, but you don't want to find yourself in the midst of investigating a complex research project and realize that you don't have enough prior research to draw from for your analysis. There's nothing inherently wrong with original research, but you must choose research problems that can be supported, in some way, by the resources available to you. If you are not sure if something is researchable, don't assume that it isn't if you don't find information right away--seek help from a librarian !

NOTE: Do not confuse a research problem with a research topic. A topic is something to read and obtain information about, whereas a problem is something to be solved or framed as a question raised for inquiry, consideration, or solution, or explained as a source of perplexity, distress, or vexation. In short, a research topic is something to be understood; a research problem is something that needs to be investigated.

IV. Asking Analytical Questions about the Research Problem

Research problems in the social and behavioral sciences are often analyzed around critical questions that must be investigated. These questions can be explicitly listed in the introduction [i.e., "This study addresses three research questions about women's psychological recovery from domestic abuse in multi-generational home settings..."], or, the questions are implied in the text as specific areas of study related to the research problem. Explicitly listing your research questions at the end of your introduction can help in designing a clear roadmap of what you plan to address in your study, whereas, implicitly integrating them into the text of the introduction allows you to create a more compelling narrative around the key issues under investigation. Either approach is appropriate.

The number of questions you attempt to address should be based on the complexity of the problem you are investigating and what areas of inquiry you find most critical to study. Practical considerations, such as, the length of the paper you are writing or the availability of resources to analyze the issue can also factor in how many questions to ask. In general, however, there should be no more than four research questions underpinning a single research problem.

Given this, well-developed analytical questions can focus on any of the following:

- Highlights a genuine dilemma, area of ambiguity, or point of confusion about a topic open to interpretation by your readers;

- Yields an answer that is unexpected and not obvious rather than inevitable and self-evident;

- Provokes meaningful thought or discussion;

- Raises the visibility of the key ideas or concepts that may be understudied or hidden;

- Suggests the need for complex analysis or argument rather than a basic description or summary; and,

- Offers a specific path of inquiry that avoids eliciting generalizations about the problem.

NOTE: Questions of how and why concerning a research problem often require more analysis than questions about who, what, where, and when. You should still ask yourself these latter questions, however. Thinking introspectively about the who, what, where, and when of a research problem can help ensure that you have thoroughly considered all aspects of the problem under investigation and helps define the scope of the study in relation to the problem.

V. Mistakes to Avoid

Beware of circular reasoning! Do not state the research problem as simply the absence of the thing you are suggesting. For example, if you propose the following, "The problem in this community is that there is no hospital," this only leads to a research problem where:

- The need is for a hospital

- The objective is to create a hospital

- The method is to plan for building a hospital, and

- The evaluation is to measure if there is a hospital or not.

This is an example of a research problem that fails the "So What?" test . In this example, the problem does not reveal the relevance of why you are investigating the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., perhaps there's a hospital in the community ten miles away]; it does not elucidate the significance of why one should study the fact there is no hospital in the community [e.g., that hospital in the community ten miles away has no emergency room]; the research problem does not offer an intellectual pathway towards adding new knowledge or clarifying prior knowledge [e.g., the county in which there is no hospital already conducted a study about the need for a hospital, but it was conducted ten years ago]; and, the problem does not offer meaningful outcomes that lead to recommendations that can be generalized for other situations or that could suggest areas for further research [e.g., the challenges of building a new hospital serves as a case study for other communities].

Alvesson, Mats and Jörgen Sandberg. “Generating Research Questions Through Problematization.” Academy of Management Review 36 (April 2011): 247-271 ; Choosing and Refining Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; D'Souza, Victor S. "Use of Induction and Deduction in Research in Social Sciences: An Illustration." Journal of the Indian Law Institute 24 (1982): 655-661; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); How to Write a Research Question. The Writing Center. George Mason University; Invention: Developing a Thesis Statement. The Reading/Writing Center. Hunter College; Problem Statements PowerPoint Presentation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Procter, Margaret. Using Thesis Statements. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518; Trochim, William M.K. Problem Formulation. Research Methods Knowledge Base. 2006; Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Walk, Kerry. Asking an Analytical Question. [Class handout or worksheet]. Princeton University; White, Patrick. Developing Research Questions: A Guide for Social Scientists . New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2009; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Theoretical Framework >>

- Last Updated: Jun 18, 2024 10:45 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

The Research Problem & Statement

What they are & how to write them (with examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | March 2023

If you’re new to academic research, you’re bound to encounter the concept of a “ research problem ” or “ problem statement ” fairly early in your learning journey. Having a good research problem is essential, as it provides a foundation for developing high-quality research, from relatively small research papers to a full-length PhD dissertations and theses.

In this post, we’ll unpack what a research problem is and how it’s related to a problem statement . We’ll also share some examples and provide a step-by-step process you can follow to identify and evaluate study-worthy research problems for your own project.

Overview: Research Problem 101

What is a research problem.

- What is a problem statement?

Where do research problems come from?

- How to find a suitable research problem

- Key takeaways

A research problem is, at the simplest level, the core issue that a study will try to solve or (at least) examine. In other words, it’s an explicit declaration about the problem that your dissertation, thesis or research paper will address. More technically, it identifies the research gap that the study will attempt to fill (more on that later).

Let’s look at an example to make the research problem a little more tangible.

To justify a hypothetical study, you might argue that there’s currently a lack of research regarding the challenges experienced by first-generation college students when writing their dissertations [ PROBLEM ] . As a result, these students struggle to successfully complete their dissertations, leading to higher-than-average dropout rates [ CONSEQUENCE ]. Therefore, your study will aim to address this lack of research – i.e., this research problem [ SOLUTION ].

A research problem can be theoretical in nature, focusing on an area of academic research that is lacking in some way. Alternatively, a research problem can be more applied in nature, focused on finding a practical solution to an established problem within an industry or an organisation. In other words, theoretical research problems are motivated by the desire to grow the overall body of knowledge , while applied research problems are motivated by the need to find practical solutions to current real-world problems (such as the one in the example above).

As you can probably see, the research problem acts as the driving force behind any study , as it directly shapes the research aims, objectives and research questions , as well as the research approach. Therefore, it’s really important to develop a very clearly articulated research problem before you even start your research proposal . A vague research problem will lead to unfocused, potentially conflicting research aims, objectives and research questions .

What is a research problem statement?

As the name suggests, a problem statement (within a research context, at least) is an explicit statement that clearly and concisely articulates the specific research problem your study will address. While your research problem can span over multiple paragraphs, your problem statement should be brief , ideally no longer than one paragraph . Importantly, it must clearly state what the problem is (whether theoretical or practical in nature) and how the study will address it.

Here’s an example of a statement of the problem in a research context:

Rural communities across Ghana lack access to clean water, leading to high rates of waterborne illnesses and infant mortality. Despite this, there is little research investigating the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects within the Ghanaian context. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the effectiveness of such projects in improving access to clean water and reducing rates of waterborne illnesses in these communities.

As you can see, this problem statement clearly and concisely identifies the issue that needs to be addressed (i.e., a lack of research regarding the effectiveness of community-led water supply projects) and the research question that the study aims to answer (i.e., are community-led water supply projects effective in reducing waterborne illnesses?), all within one short paragraph.

Need a helping hand?