Best 3 Executive Secretary Cover Letter Samples

Executive secretaries are trained professionals who are expected to provide administrative and clerical support to high-level management personnel.

During a typical working day, they perform a number of tasks such as managing correspondence, preparing presentations, and handling scheduling which is essential for the smooth running of an executive’s office.

When an executive secretary applies for a job, they must ensure that their cover letter reflects their administrative abilities. Since this position usually requires an individual to be an expert in carrying out many diverse tasks, it is important to highlight the ability to perform many tasks at the same time.

The following cover letter will provide you with an idea on how to write an excellent cover letter for an executive secretary resume.

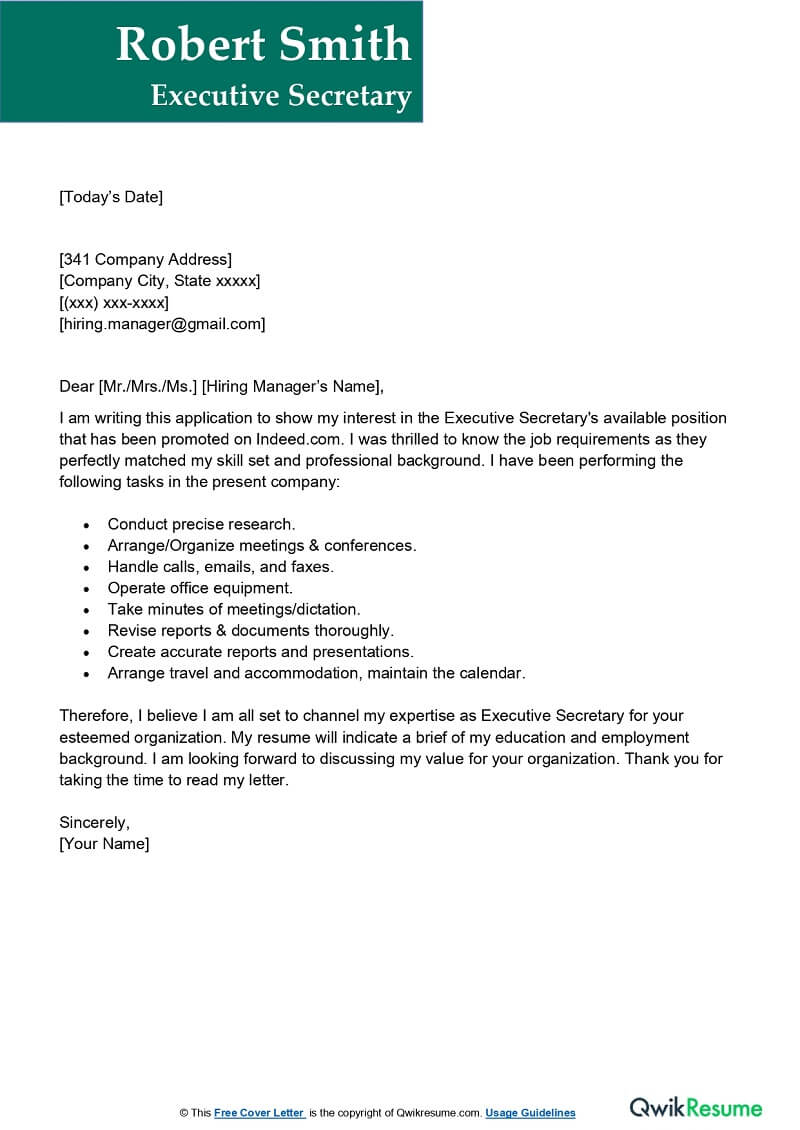

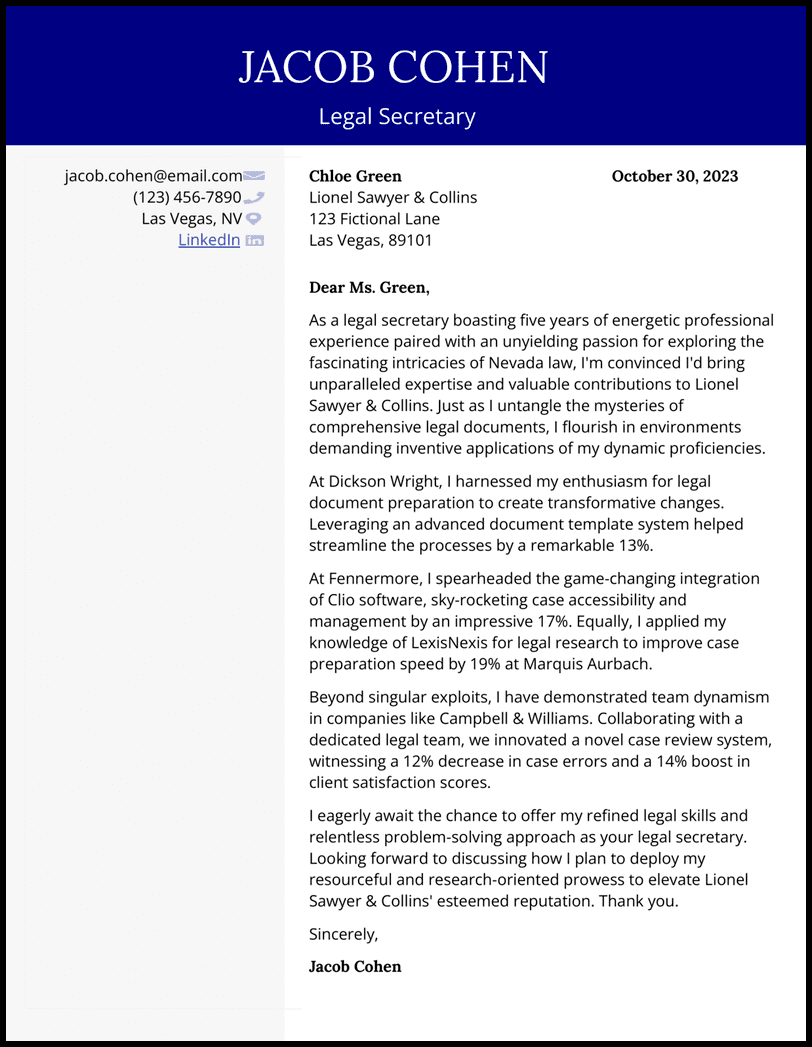

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Sample 1 Experience: 15+ Years

Samuel Staley (010) 000-3333 sameul.staley @ email . com

October 24, 2020

Mr. Ashton Kirk Recruiter Asphalt 300 Moldway Road Tulsa, OK 77911

Dear Mr. Kirk:

With extensive administrative support experience, as well as attention to detail, I am confident I perfectly meet the requirements that you have specified in your advertisement for the Executive Secretary position. Dedicated, professional, and hardworking are three adjectives that have been used for me by my supervisor quite often over the 15 years that I have worked in the secretarial roles.

My expertise as an executive secretary is backed by years of performing general secretarial work at Clockwise. I am well versed in revamping the scheduling and filing system, thereby ensuring quick and efficient management of the executive meetings and conference schedules and reduction of paperwork. At my previous place of work, I was promoted to the position of an executive secretary owing to my ability to gauge and meet high-level management’s official needs and my professionalism in carrying out the core secretarial functions of the office.

Over the years, I have developed extreme proficiency in preparing the meeting of minutes, press releases, and managing high-end executive correspondence. I have an inherent ability to deal with internal conflicts and provide practical solutions constructively. My people and communication skills are especially excellent, where customers, consultants, vendors, and government agencies are concerned, which would bring great benefit to your company.

This vast and diverse pool of my experience will help me contribute successfully. I would like to meet with you to discuss how I may be an asset to your organization. The enclosed resume will provide you with a deep insight into my abilities.

Thank you for your time and consideration.

(Signature) Samuel Staley (010) 000-3333 sameul.staley @ email . com

Enc. Resume

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Sample 2 Experience: 10+ Years

Alan Martin 56 Flake Lane, Ocala, FL 87221 (000) 323-3432 anna.martin @ email . com

Mr. Peter Jones CEO Wayzata Associates 890 Berkley Towers Ocala, FL 87221

Dear Mr. Jones:

I am writing in response to your ad for an Executive Secretary, as cited in yesterday’s Florida Times. The opportunity is very exciting for me since my profile fully complements your job description. Possessing 5+ year’ extensive experience in clerical and administrative capacities, I fully specialize in all the required skills.

The following is a brief overview of my qualifications in alignment with your desired skills and competencies.

- 10+ years in public dealing and a demonstrated ability to understand PR protocols associated with this position.

- Expert in handling the front desk and managing appointments for busy calendar schedules of executives and high officials.

- Office management and administrative skills.

- Familiar with bookkeeping, corresponding handling, and payroll processing.

- Proficient in usage of all applications associated with MS Office suite in addition to front desk software and a typing speed of 50 WPM.

I am confident that my secretarial expertise will play a major role in simplifying your official tasks and relieve you in many ways.

In order to briefly discuss my skills and capabilities, I’d like to meet with you soon. Thank you for your time and consideration.

Alan Martin

(000) 333-4444

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Sample 3 Experience: 5+ Years

Mr. Max Gabriel Manager Human Resources Zale Corporation 490 Parkway Avenue Ewing, NJ 72015

Dear Mr. Gabriel:

Performance – Analytic Thinking – Results. These are only three of the many values that I can bring to Zale Corporation in the role of an Executive Secretary. I have a broad spectrum of administrative experience spanning over five years which would enable me to meet and exceed your expectations.

My academic qualifications, professional experiences and personal strengths reveal a great ability to handle high-end executives’ support, budget management, scheduling, and records keeping tasks.

I have a proven track record of presenting a pleasant and professional attitude and have the ability to handle most queries independently. Also, I possess ample experience in managing travel and accommodation details and possess the technical knowledge needed for creating presentations for meetings and seminars. I have been credited with implementing a sophisticated scheduling system that was useful in handling projects having a tight deadline.

As a proactive and diplomatic professional, I would welcome the opportunity to demonstrate how I can provide benefit to your organization using my skills and expertise. If you prefer, you may reach me at (000) 000-3333.

Sincere regards,

Zara Elijah

Enc: Resume

- 5 Executive Secretary Summary Profile for Resume

- Executive Secretary Reference and Recommendation Letter Sample

- Executive Secretary Resume Example and Guide

- Top 10 Executive Secretary Resume Objective Examples (+How to Write)

6 Executive Secretary Cover Letter Examples

Executive secretary cover letter examples.

When applying for a job as an executive secretary, a well-crafted cover letter can make all the difference. In today's competitive job market, a generic cover letter simply won't cut it. Employers are looking for candidates who can demonstrate their skills, experience, and enthusiasm for the role. A tailored cover letter allows you to highlight your qualifications and show why you are the perfect fit for the position.

In this article, we will provide you with a collection of executive secretary cover letter examples that you can use as inspiration when crafting your own. Each example will showcase different approaches and highlight various key elements that can help your application stand out. By following the examples and incorporating their key takeaways, you can create a compelling cover letter that grabs the attention of hiring managers and sets you apart from the competition.

So, whether you're an experienced executive secretary looking to switch companies or a recent graduate seeking your first role in the field, these cover letter examples will provide you with valuable insights and guidance. Let's dive in and explore the world of executive secretary cover letters!

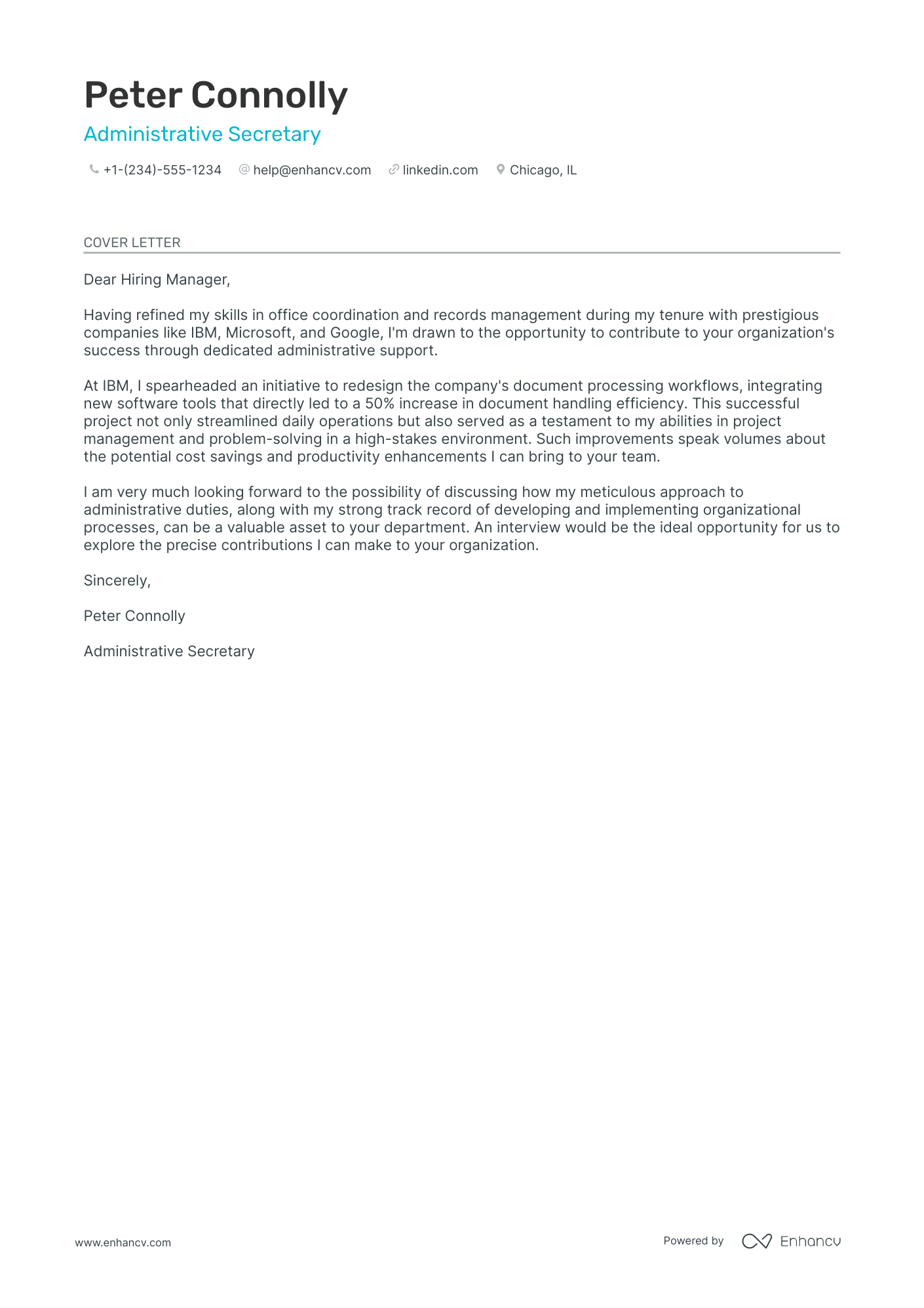

Example 1: Executive Secretary Cover Letter Example

Key takeaways.

Samantha's cover letter effectively showcases her extensive experience as an Executive Assistant, Office Manager, and Executive Secretary, positioning her as a highly qualified candidate for the Executive Secretary position at CNN.

It's crucial to highlight your relevant job history and emphasize your experience in similar roles. This demonstrates your familiarity with the responsibilities and challenges of the position, increasing your chances of being considered.

She highlights two key achievements - implementing a digital filing system that reduced document retrieval time by 40% and successfully organizing a high-profile industry conference as the Office Manager at NBCUniversal. These accomplishments demonstrate her ability to streamline processes, drive efficiency, and handle complex projects.

Quantify your achievements whenever possible to provide concrete evidence of your skills and accomplishments. This allows the hiring manager to assess the impact you can make in the role.

Samantha also aligns herself with CNN's mission and values, emphasizing her belief in the power of journalism to shape public opinion and drive positive change. This shows her genuine interest in the organization and her commitment to its goals.

Research the company and understand its core values and mission. Incorporate this knowledge into your cover letter to demonstrate your alignment with the company culture and your enthusiasm for contributing to its success.

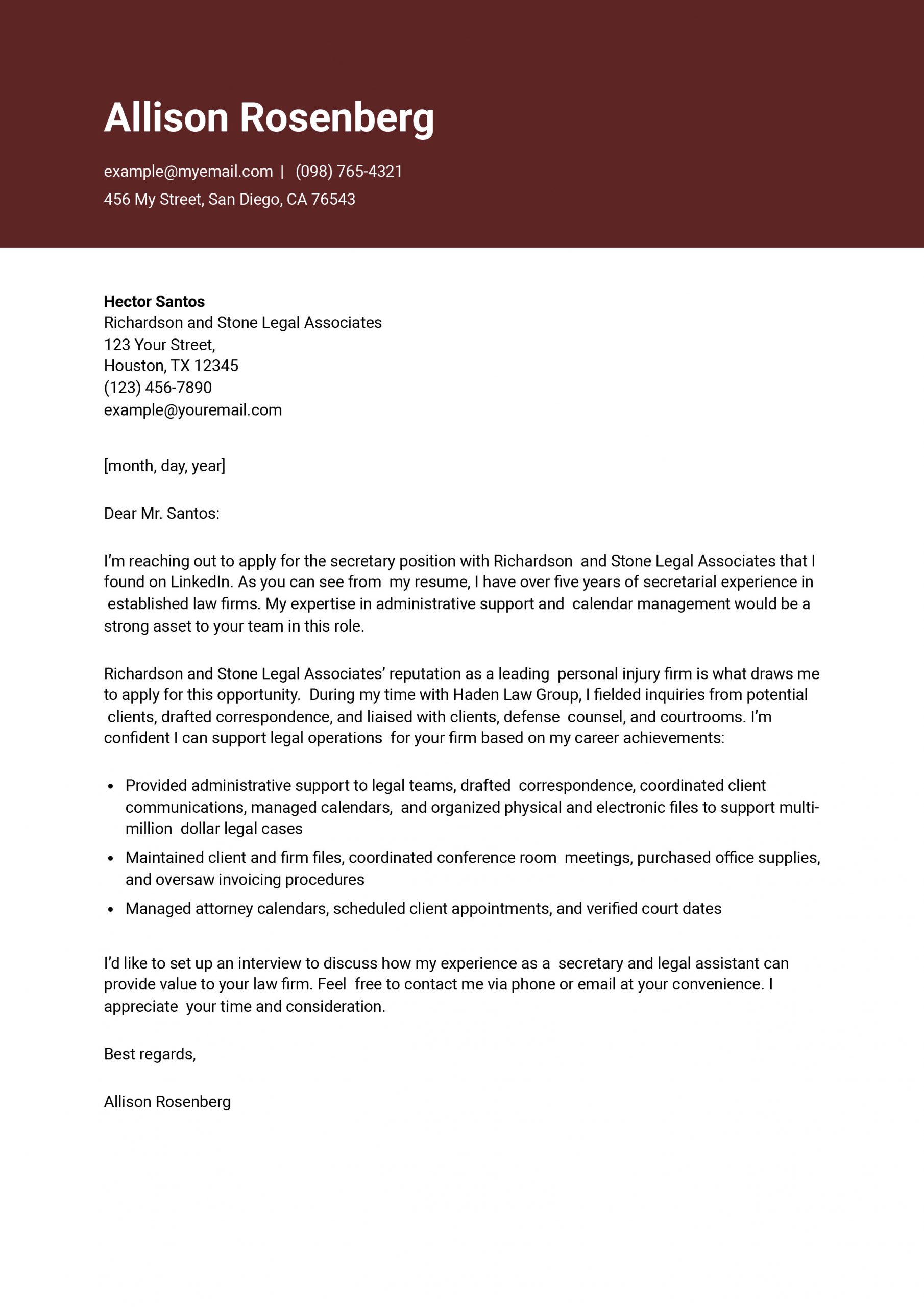

Example 2: Legal Executive Secretary Cover Letter

Emily's cover letter effectively highlights her relevant experience and skills in legal administration, positioning her as an ideal candidate for the Legal Executive Secretary position at the Law Offices of Smith & Johnson.

When applying for a legal support role, it's crucial to showcase your understanding of legal processes and your ability to handle administrative tasks efficiently. This demonstrates your readiness to contribute immediately to the firm's operations.

She emphasizes her experience in managing legal documents, conducting legal research, and providing administrative support to attorneys. By mentioning specific tasks such as preparing and proofreading legal documents, maintaining an organized filing system, and managing calendars, Emily demonstrates her attention to detail and ability to handle multiple responsibilities.

Highlight specific tasks and responsibilities that are directly relevant to the position you are applying for. This shows that you have the necessary skills and experience to excel in the role.

Emily also mentions her experience in supervising a team of legal assistants, showcasing her leadership and management skills. This demonstrates her ability to handle complex projects, coordinate with others, and ensure timely completion of tasks.

If you have experience in a managerial or supervisory role, be sure to mention it in your cover letter. This highlights your ability to take on additional responsibilities and effectively manage a team.

To further strengthen her application, Emily could have mentioned any specific software or technology skills she possesses that are relevant to the role.

If you have experience with legal software, document management systems, or other technology commonly used in law firms, be sure to mention it in your cover letter. This demonstrates your ability to adapt to the firm's existing tools and systems, making you a valuable asset to the team.

Example 3: Medical Executive Secretary Cover Letter

Jennifer's cover letter effectively showcases her experience and skills as a medical office professional, making her a strong candidate for the Medical Executive Secretary position at Mayo Clinic.

When applying for a medical administrative role, it is crucial to highlight your experience in managing patient records, scheduling appointments, and providing administrative support to healthcare professionals. This demonstrates your familiarity with the specific requirements of medical office operations.

Jennifer emphasizes her attention to detail, organizational skills, and ability to multitask, which are essential qualities for a successful medical executive secretary.

Highlighting your organizational skills and ability to handle a high volume of tasks with accuracy is important in a medical administrative role. This demonstrates your capacity to manage complex administrative responsibilities in a fast-paced healthcare environment.

She also highlights her experience in supporting executive teams and managing complex calendars, demonstrating her ability to handle confidential information and coordinate the schedules of multiple individuals.

Emphasizing your experience in supporting executives and managing calendars showcases your professionalism, discretion, and ability to handle sensitive information. These skills are vital in a medical executive secretary role.

Jennifer concludes her letter by expressing her admiration for Mayo Clinic's reputation and mission, demonstrating her enthusiasm and genuine interest in working for the organization.

When applying to a specific healthcare institution, it is important to convey your knowledge of and alignment with the organization's values and goals. This shows your dedication to contributing to the organization's mission and culture.

Example 4: Executive Secretary to CEO Cover Letter Example

Michael's cover letter effectively positions him as a strong candidate for the Executive Secretary to CEO position at Google by showcasing his relevant experience and highlighting his key achievements.

When applying for a role as an executive secretary to a CEO, it is crucial to emphasize your experience in supporting high-level executives and managing confidential information. This demonstrates your ability to handle sensitive tasks and maintain professionalism.

Michael highlights his achievement in implementing a digital filing system at Facebook, which improved document organization and retrieval. This showcases his problem-solving skills and commitment to efficiency.

When discussing achievements in your cover letter, focus on quantifiable results and how they positively impacted the organization. This demonstrates your ability to make tangible contributions and adds credibility to your application.

The cover letter could further emphasize Michael's ability to handle complex tasks and his strong communication skills, which are essential for an executive secretary role.

Don't forget to mention your ability to handle multiple responsibilities, coordinate meetings and events, and effectively communicate with various stakeholders. These skills are crucial for success in an executive secretary role and should be highlighted in your cover letter.

Example 5: Executive Secretary to Board of Directors Cover Letter

Nicole's cover letter effectively highlights her relevant experience and skills as an executive secretary, positioning her as the ideal candidate for the Executive Secretary to the Board of Directors position at Amazon.

When applying for a role as an executive secretary, it is crucial to emphasize your experience supporting high-level executives and managing complex administrative tasks. This demonstrates your ability to handle confidential information and perform under pressure.

Nicole showcases her experience in managing calendars, coordinating travel arrangements, organizing meetings, and preparing meeting materials. These responsibilities exemplify her strong organizational skills and attention to detail.

Highlight specific tasks and responsibilities that are directly relevant to the executive secretary role. This demonstrates your practical experience and expertise in supporting executives and managing board-related activities.

Nicole also mentions her experience in overseeing budgets, coordinating large-scale events, and working collaboratively with cross-functional teams. These additional skills demonstrate her ability to handle diverse responsibilities and work effectively in a fast-paced environment.

If you have experience in areas beyond traditional executive support, such as event coordination or budget management, be sure to mention these skills. This shows your versatility and ability to contribute to broader organizational goals.

Overall, Nicole's cover letter effectively positions her as a highly qualified candidate with the necessary skills and experience to excel in the role of Executive Secretary to the Board of Directors at Amazon.

Example 6: Government Executive Secretary Cover Letter

Thomas' cover letter effectively highlights his relevant experience and skills, positioning him as a strong candidate for the Government Executive Secretary position at the United States Department of State.

When applying for a government role, it's crucial to emphasize your experience in working within federal agencies. This demonstrates your familiarity with government processes and regulations, making you a valuable asset to the organization.

Thomas showcases his administrative expertise by highlighting his accomplishments in previous roles, such as managing calendars, scheduling meetings, and organizing travel arrangements. These tasks are essential for supporting high-level executives and ensuring smooth operations.

Highlight your specific administrative skills and achievements to demonstrate your ability to handle the responsibilities of the role effectively. This shows that you have a track record of success and can contribute immediately to the organization.

Thomas also emphasizes his leadership and organizational skills, which he developed as an Office Manager at the Central Intelligence Agency. By implementing streamlined processes and reducing costs, he demonstrates his ability to improve efficiency and drive results.

If you have experience in a leadership role, emphasize your ability to manage teams and implement process improvements. These skills are highly valued in administrative positions and can set you apart from other candidates.

Additionally, Thomas highlights his experience in managing sensitive information and coordinating complex projects, essential skills for a Government Executive Secretary. He mentions his ability to handle multiple projects simultaneously and maintain confidentiality, which are critical in supporting high-level executives in their strategic initiatives.

When applying for positions that involve handling confidential information or coordinating complex projects, emphasize your ability to maintain confidentiality and manage multiple tasks efficiently. These skills are essential for success in the role and demonstrate your suitability for the position.

Skills To Highlight

As an executive secretary, your cover letter should highlight the unique skills that make you a strong candidate for the role. These key skills include:

Strong Organizational Abilities : As an executive secretary, you will be responsible for managing the administrative tasks of a high-level executive or a team of executives. It is crucial to showcase your strong organizational abilities, including your ability to prioritize tasks, manage calendars, coordinate meetings and travel arrangements, and maintain files and records. Highlight any experience you have in managing complex schedules and juggling multiple priorities effectively.

Communication Skills : Excellent communication skills are essential for an executive secretary. You will be the primary point of contact for internal and external stakeholders, including executives, clients, and vendors. Your cover letter should demonstrate your ability to communicate professionally and effectively both verbally and in writing. Emphasize your experience in drafting and proofreading correspondence, preparing reports and presentations, and handling phone calls and emails with tact and diplomacy.

Attention to Detail : Attention to detail is a critical skill for an executive secretary, as you will be responsible for ensuring accuracy and precision in all administrative tasks. From reviewing documents and contracts to proofreading reports and presentations, your cover letter should showcase your keen eye for detail. Highlight any experience you have in conducting thorough quality checks, identifying errors, and implementing corrective measures to maintain high standards of accuracy.

Time Management : As an executive secretary, you will often be working on multiple projects with tight deadlines. It is crucial to demonstrate your ability to manage your time effectively and prioritize tasks accordingly. Your cover letter should highlight your experience in managing competing priorities, meeting deadlines, and handling unexpected changes in schedules or priorities. Discuss any strategies or tools you have used to stay organized and meet deadlines successfully.

Proficiency in Office Software : Proficiency in office software is a must-have skill for an executive secretary. Your cover letter should mention your proficiency in using common office software, such as Microsoft Office Suite (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Outlook), as well as any specialized software or tools relevant to the role. Highlight specific tasks or projects where you have utilized these software skills effectively, such as creating spreadsheets, preparing presentations, or managing email accounts.

Professional Discretion : As an executive secretary, you will often handle sensitive and confidential information. It is vital to demonstrate your ability to maintain professional discretion and handle confidential matters with utmost confidentiality and integrity. Your cover letter should emphasize your understanding of the importance of confidentiality and your commitment to maintaining the highest ethical standards in your work.

By highlighting these key skills in your cover letter, you can demonstrate to potential employers that you have the necessary qualifications and abilities to excel as an executive secretary. Remember to provide specific examples and quantify your achievements whenever possible to make your cover letter more impactful.

Common Mistakes To Avoid

When crafting your executive secretary cover letter, it is important to avoid these common mistakes:

Including Irrelevant Information : Your cover letter should be focused on showcasing your qualifications and experiences that are directly relevant to the executive secretary role. Avoid including irrelevant information or personal details that do not contribute to your candidacy.

Using Generic Language : A generic cover letter will not make you stand out from other applicants. Avoid using clichés and generic language that could apply to any job. Instead, tailor your cover letter to the specific requirements and responsibilities of the executive secretary position.

Failing to Demonstrate Knowledge of the Company : Employers want to see that you have done your research and are genuinely interested in their organization. Failing to mention specific details about the company or not showcasing your understanding of their industry can give the impression that you are not truly invested in the role.

Not Showcasing Specific Achievements and Contributions : Your cover letter is an opportunity to highlight your accomplishments and how you have added value in your previous roles. Avoid simply listing your job duties; instead, focus on specific achievements and contributions that demonstrate your skills, expertise, and impact as an executive secretary.

Neglecting to Customize Your Cover Letter : Each cover letter should be tailored to the specific job you are applying for. Avoid using a generic cover letter for multiple applications. Take the time to customize your cover letter to match the requirements and qualifications outlined in the job description.

Neglecting to Proofread and Edit : Spelling and grammatical errors can create a negative impression and indicate a lack of attention to detail. Always proofread your cover letter and consider having someone else review it as well to catch any mistakes or inconsistencies.

Being Too Long or Too Short : Your cover letter should be concise yet comprehensive. Avoid writing a cover letter that is too long and includes unnecessary details. At the same time, make sure your cover letter provides enough information to showcase your qualifications and make a compelling case for your candidacy.

Focusing Too Much on Yourself : While it is important to highlight your qualifications and experiences, it is equally important to emphasize how you can contribute to the company's success. Avoid focusing solely on what the company can do for you; instead, demonstrate your understanding of the company's needs and how you can meet them as an executive secretary.

By avoiding these common mistakes, you can create a strong executive secretary cover letter that effectively highlights your qualifications and convinces employers of your suitability for the role.

In conclusion, a well-crafted cover letter is essential for executive secretaries who want to stand out in today's competitive job market. By following the examples provided in this article and tailoring their cover letter to each specific role and organization, candidates can greatly enhance their chances of landing a coveted position.

The key takeaways from the cover letter examples are:

Clearly highlight relevant skills and experiences that align with the job requirements.

By showcasing their expertise in areas such as calendar management, travel coordination, and document preparation, executive secretaries can demonstrate their ability to handle the responsibilities of the role effectively.

Emphasize strong communication and interpersonal skills.

Effective communication and the ability to collaborate with colleagues and stakeholders are crucial for executive secretaries. By highlighting their excellent verbal and written communication skills, candidates can showcase their ability to maintain effective working relationships.

Show enthusiasm and passion for the organization.

Employers are looking for candidates who are genuinely interested in their organization and its mission. By expressing enthusiasm and explaining why they are excited about the opportunity to work for a particular company, executive secretaries can demonstrate their commitment and dedication.

By avoiding common mistakes such as generic salutations, lack of customization, and excessive use of jargon, executive secretaries can ensure that their cover letter stands out for all the right reasons.

In today's competitive job market, a well-written cover letter can be the key to landing a desired executive secretary position. By following the tips and examples provided in this article, candidates can create a compelling cover letter that showcases their skills, experiences, and enthusiasm, ultimately increasing their chances of success. So, take the time to craft a strong cover letter and make a lasting impression on potential employers.

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Example for 2024 (Skills & Templates)

Create a standout executive secretary cover letter with our online platform. browse professional templates for all levels and specialties. land your dream role today.

If you're an executive secretary looking to make the right impression, crafting a compelling cover letter is crucial. Our guide will provide you with tips, tricks, and examples to help you stand out from the competition and display how your skills, experience, and passion make you the best candidate for the job. Take the first steps towards your dream career with us today!

We will cover:

- How to write a cover letter, no matter your industry or job title.

- What to put on a cover letter to stand out.

- The top skills employers from every industry want to see.

- How to build a cover letter fast with our professional Cover Letter Builder .

- What a cover letter template is, and why you should use it.

Related Cover Letter Examples

- Billing Representative Cover Letter Sample

- Program Associate Cover Letter Sample

- Title Searcher Cover Letter Sample

- Desk Receptionist Cover Letter Sample

- Insurance Processor Cover Letter Sample

- Reimbursement Specialist Cover Letter Sample

- Receiving Clerk Cover Letter Sample

- Business Support Cover Letter Sample

- Purchasing Assistant Cover Letter Sample

- Document Clerk Cover Letter Sample

- Administrative Secretary Cover Letter Sample

- Insurance Verification Specialist Cover Letter Sample

- Clerical Associate Cover Letter Sample

- Receiver Cover Letter Sample

- Insurance Clerk Cover Letter Sample

- Administrative Clerk Cover Letter Sample

- Office Manager Cover Letter Sample

- Billing Coordinator Cover Letter Sample

- Telephone Operator Cover Letter Sample

- Inventory Control Specialist Cover Letter Sample

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Sample

Dear Hiring Manager,

I am writing to express my interest in the Executive Secretary position advertised on your company's website. With my extensive administrative and secretarial experience, coupled with my passion for professional development, I believe I could make a substantial contribution to your team.

Possessing more than five years' experience as an executive-level secretary, I have developed a repertoire of skills and capabilities that I believe will benefit your company. I have extensive experience in the following areas:

- Administrative support: Supported senior executives by managing calendars, executing tasks, coordinating meetings, and handling correspondence.

- Communication: Efficiently liaised with internal and external stakeholders, thus facilitating timely and effective communication.

- Document management: Organized and maintained essential files, thus ensuring quick access to vital information.

- Problem-solving: Deftly handled unanticipated situations, effectively resolving issues in a timely and professional manner.

- Project coordination: Successfully coordinated complex tasks, meeting strict deadlines while ensuring top-quality execution.

I also bring a strong aptitude for technology, having used diverse office software and productivity tools in my previous roles. My proficiency in these areas can be used to enhance efficiency and productivity in your team.

In my previous position at XYZ Corporation, I worked as an Executive Assistant for the CEO. This role required high levels of organization, adaptability, and attention to detail - all skills that are crucial for effective secretariat work. My experience working in this demanding environment has equipped me with the skill set required to thrive in the role at your company.

I am drawn to your company due to its commitment to innovation and quality - values that align with my professional ethos. In addition to my strong administrative skills, my ability to work well under pressure and multitask effectively will make me an asset to your team.

I look forward to the opportunity of discussing my application with you further. I believe I can bring valuable skills and experiences that will complement your team. Thank you for considering my application.

Sincerely, [Your Name]

Why Do you Need a Executive Secretary Cover Letter?

An Executive Secretary cover letter is an essential addition to your job application process. This document communicates in detail your specific skills, qualifications, and experiences that make you the best fit for the role. Here are several reasons why you need an Executive Secretary cover letter:

- First Impression: A cover letter helps to make a grand first impression on an employer. The format, tone, and content of the letter allow the employer to form a preliminary impression of your communication skills, professionalism, and attention to detail.

- Personal Touch: Your resume provides an outline of your skills and experiences. However, it's your cover letter that adds a personalized touch to your application. It showcases your personality and gives the employer an insight on what to expect from you.

- Showcase Your Skills: A cover letter is a great platform to talk about your previous experiences and how they shaped your skills. As an Executive Secretary, you can highlight your exceptional organizational skills, ability to handle confidential matters, proficiency in business correspondence, and other relevant skills that might not come through in a resume.

- Chance to Differentiate: A cover letter allows you to differentiate yourself from other candidates. You can explain why you are particularly interested in the company or the role, provide examples of how you can add value to the organization, and mention any relevant achievements or accolades.

- Address Gaps: If there are any gaps in your employment history or you are changing careers, a cover letter gives you the chance to address these issues and put them in a positive light.

- Show Enthusiasm: Finally, enthusiasm is contagious! A cover letter is an excellent vehicle to express your passion for the role, the company, and the industry it operates in. This is more likely to result in call-backs for interviews than a resume alone.

A Few Important Rules To Keep In Mind

When drafting an Executive Secretary cover letter, it's vital to adhere to specific rules to craft a piece that's not only professional but also capable of grabbing the attention of your potential employer. Below are a few guidelines to help you create a top-notch cover letter.

- Formal style: Use a formal style of writing to show your professionalism. Avoid using slang or too casual language.

- Address the recipient appropriately: Always address the recipient formally by using their proper title and surname. If you do not know their name, use a general term like "Hiring Manager.

- Echo the job description: Reflect the language of the job description in your cover letter to show that you understand the role, its requirements, and possess the necessary skills. Do not copy and paste the job description into your letter; instead, echo specific phrases.

- Providing specific examples: Cite concrete examples where you exercised skills relevant to the job posting. This helps the reader understand your competence and experience in various situations.

- Keep it concise: Your cover letter should be direct and concise. Aim to keep your letter within one page to grab the reader's attention.

- Proofread: It is vital to proofread your letter for grammar, spelling, or punctuation mistakes. These errors can detract from your professionalism and may cost you the job opportunity.

- Format appropriately: A typical letter format includes your contact information, the date, the recipient's contact information, a salutation, the body, and the closing. Make sure all these elements are included.

- End on a positive note: Concluding your cover letter positively can leave an impression on the recipient. A note of gratitude for considering your application or a statement of enthusiasm about the opportunity to further discuss your suitability for the role is a great way to end.

What's The Best Structure For Executive Secretary Cover Letters?

After creating an impressive Executive Secretary resume , the next step is crafting a compelling cover letter to accompany your job applications. It's essential to remember that your cover letter should maintain a formal tone and follow a recommended structure. But what exactly does this structure entail, and what key elements should be included in a Executive Secretary cover letter? Let's explore the guidelines and components that will make your cover letter stand out.

Key Components For Executive Secretary Cover Letters:

- Your contact information, including the date of writing

- The recipient's details, such as the company's name and the name of the addressee

- A professional greeting or salutation, like "Dear Mr. Levi,"

- An attention-grabbing opening statement to captivate the reader's interest

- A concise paragraph explaining why you are an excellent fit for the role

- Another paragraph highlighting why the position aligns with your career goals and aspirations

- A closing statement that reinforces your enthusiasm and suitability for the role

- A complimentary closing, such as "Regards" or "Sincerely," followed by your name

- An optional postscript (P.S.) to add a brief, impactful note or mention any additional relevant information.

Cover Letter Header

A header in a cover letter should typically include the following information:

- Your Full Name: Begin with your first and last name, written in a clear and legible format.

- Contact Information: Include your phone number, email address, and optionally, your mailing address. Providing multiple methods of contact ensures that the hiring manager can reach you easily.

- Date: Add the date on which you are writing the cover letter. This helps establish the timeline of your application.

It's important to place the header at the top of the cover letter, aligning it to the left or center of the page. This ensures that the reader can quickly identify your contact details and know when the cover letter was written.

Cover Letter Greeting / Salutation

A greeting in a cover letter should contain the following elements:

- Personalized Salutation: Address the hiring manager or the specific recipient of the cover letter by their name. If the name is not mentioned in the job posting or you are unsure about the recipient's name, it's acceptable to use a general salutation such as "Dear Hiring Manager" or "Dear [Company Name] Recruiting Team."

- Professional Tone: Maintain a formal and respectful tone throughout the greeting. Avoid using overly casual language or informal expressions.

- Correct Spelling and Title: Double-check the spelling of the recipient's name and ensure that you use the appropriate title (e.g., Mr., Ms., Dr., or Professor) if applicable. This shows attention to detail and professionalism.

For example, a suitable greeting could be "Dear Ms. Johnson," or "Dear Hiring Manager," depending on the information available. It's important to tailor the greeting to the specific recipient to create a personalized and professional tone for your cover letter.

Cover Letter Introduction

An introduction for a cover letter should capture the reader's attention and provide a brief overview of your background and interest in the position. Here's how an effective introduction should look:

- Opening Statement: Start with a strong opening sentence that immediately grabs the reader's attention. Consider mentioning your enthusiasm for the job opportunity or any specific aspect of the company or organization that sparked your interest.

- Brief Introduction: Provide a concise introduction of yourself and mention the specific position you are applying for. Include any relevant background information, such as your current role, educational background, or notable achievements that are directly related to the position.

- Connection to the Company: Demonstrate your knowledge of the company or organization and establish a connection between your skills and experiences with their mission, values, or industry. Showcasing your understanding and alignment with their goals helps to emphasize your fit for the role.

- Engaging Hook: Consider including a compelling sentence or two that highlights your unique selling points or key qualifications that make you stand out from other candidates. This can be a specific accomplishment, a relevant skill, or an experience that demonstrates your value as a potential employee.

- Transition to the Body: Conclude the introduction by smoothly transitioning to the main body of the cover letter, where you will provide more detailed information about your qualifications, experiences, and how they align with the requirements of the position.

By following these guidelines, your cover letter introduction will make a strong first impression and set the stage for the rest of your application.

Cover Letter Body

Dear [Manager's Name],

I am writing to apply for the Executive Secretary position at your company, as advertised on [Job Portal's Name]. I am confident that my broad experience in executing high-level administrative duties would add immense value to your team.

Key Qualifications

- Offering over [Your Experience] years of experience working in demanding, fast-paced office environments as an Executive Secretary.

- Demonstrated expertise in arranging and scheduling meetings, organizing office documentation, managing travel itineraries, and providing comprehensive administrative support to C-suite executives.

- Highly skilled in using various office software programs including [Software Name] to create presentations, maintain account records, and streamline office operations.

I am a highly organized and self-motivated professional who is known for multitasking while maintaining attention to detail. My ability to effectively prioritize tasks, coupled with reliable problem-solving capabilities, would allow me to thrive in the role of Executive Secretary at your company.

Notable Achievements

- Received 'Employee of the Month" for my performance at [Previous Company Name].

- Implemented an innovative file management system which improved operational efficiency by [percentage].

- Successfully managed the communication flow within the office at [Previous Company Name], improving inter-departmental collaboration.

I eagerly look forward to the opportunity of discussing my application and how I could contribute to your team in further detail. Thank you for considering my application.

Complimentary Close

The conclusion and signature of a cover letter provide a final opportunity to leave a positive impression and invite further action. Here's how the conclusion and signature of a cover letter should look:

- Summary of Interest: In the conclusion paragraph, summarize your interest in the position and reiterate your enthusiasm for the opportunity to contribute to the organization or school. Emphasize the value you can bring to the role and briefly mention your key qualifications or unique selling points.

- Appreciation and Gratitude: Express appreciation for the reader's time and consideration in reviewing your application. Thank them for the opportunity to be considered for the position and acknowledge any additional materials or documents you have included, such as references or a portfolio.

- Call to Action: Conclude the cover letter with a clear call to action. Indicate your availability for an interview or express your interest in discussing the opportunity further. Encourage the reader to contact you to schedule a meeting or provide any additional information they may require.

- Complimentary Closing: Choose a professional and appropriate complimentary closing to end your cover letter, such as "Sincerely," "Best Regards," or "Thank you." Ensure the closing reflects the overall tone and formality of the letter.

- Signature: Below the complimentary closing, leave space for your handwritten signature. Sign your name in ink using a legible and professional style. If you are submitting a digital or typed cover letter, you can simply type your full name.

- Typed Name: Beneath your signature, type your full name in a clear and readable font. This allows for easy identification and ensures clarity in case the handwritten signature is not clear.

Common Mistakes to Avoid When Writing an Executive Secretary Cover Letter

When crafting a cover letter, it's essential to present yourself in the best possible light to potential employers. However, there are common mistakes that can hinder your chances of making a strong impression. By being aware of these pitfalls and avoiding them, you can ensure that your cover letter effectively highlights your qualifications and stands out from the competition. In this article, we will explore some of the most common mistakes to avoid when writing a cover letter, providing you with valuable insights and practical tips to help you create a compelling and impactful introduction that captures the attention of hiring managers. Whether you're a seasoned professional or just starting your career journey, understanding these mistakes will greatly enhance your chances of success in the job application process. So, let's dive in and discover how to steer clear of these common missteps and create a standout cover letter that gets you noticed by potential employers.

- Not addressing the recipient by name : Addressing your letter to "Sir/Madam" or "To whom it may concern" is too impersonal and may give the impression that you did not put in the effort to research the company.

- Grammatical errors : Any spelling or grammar mistakes can immediately mark you out as careless or unprofessional. Always double or triple check before sending.

- Not tailoring the letter to the job : Avoid sending a generic cover letter. Each one should be individually tailored to the specific job post and company to which you are applying.

- Lacking clear structure : Your cover letter should have an introduction, body paragraphs outlining your suitability for the role, and a conclusion. Without this structure, your letter may be difficult to follow.

- Repeating your resume verbatim : Your cover letter should complement—not duplicate—your resume. It's your chance to tell a story about why you're the right fit for the job.

- Focusing on what the company can do for you : Although it's important to express excitement about the position, your cover letter should primarily highlight what you can do for the company, not what the company can do for you.

- Being too vague : Avoid generic statements like "I'm a hard worker." Instead, use specific examples that demonstrate your skills and experience.

- Being too lengthy : Your cover letter should be concise and brief. Aim for no more than one page.

- Not following up : If you don't hear back, it's acceptable to follow up with the company about a week after you've sent your cover letter. But remember to be patient and polite in your follow-up email or phone call.

- Forgetting to include contact information : Always include your email address and phone number at the top of your cover letter.

Key Takeaways For an Executive Secretary Cover Letter

- An Executive Secretary cover letter should focus on showcasing the candidate's strong organizational and administrative skills as these are essential for the role.

- The cover letter should highlight the candidate's experience in maintaining executive schedules, coordinating meetings, and handling correspondence and communications.

- It's also important to emphasize any experience with preparing reports, presentations, and briefs for the executive. This will show that the candidate is able to handle the significant responsibilities that come with the role.

- Candidates should detail their proficiency with office software and technologies used by executive secretaries. This can include anything from Microsoft Office to scheduling and email software.

- Another key aspect to highlight in the cover letter is the candidate's interpersonal skills. Executive Secretaries are often the first point of contact between the executive and other employees or external contacts, so being approachable and professional is crucial.

- Through their cover letter, candidates should convey their ability to work efficiently under pressure and with minimal supervision, as these are key requirements of the job.

- Lastly, candidates should mention any specific qualifications or certifications they might have that are relevant to the role of an Executive Secretary, such as a degree in Business Administration or a certification in office management.

Secretary Cover Letter Examples and Templates for 2024

- Cover Letter Examples

How To Write a Secretary Cover Letter

- Cover Letter Text Examples

To generate traction during the job search, build an accomplishment-driven secretary cover letter demonstrating your communication and administrative skill sets. Show potential employers how you can help refine office operations, improve scheduling processes, and coordinate client communications effectively. Our guide includes cover letter examples and expert tips to help capture your experience and land your next job interview.

Secretary Cover Letter Templates and Examples

- Entry-Level

- Senior-Level

Writing a great secretary cover letter requires a creative approach that differs from many other types of positions. This is because your day-to-day administrative duties might not always seem like genuine achievements. That said, your contributions are vital to daily operations, and it’s important to emphasize the true value you bring to your teams and organizations. Below, we’ll provide guidance to help you capture the most compelling aspects of your professional experience in your secretary cover letter:

1. Contact information and salutation

List all essential contact information at the top of your secretary cover letter, including your name, phone number, email, and LinkedIn URL. Greet the hiring manager by name — Mr. or Ms. [Last Name]. If you can’t find the hiring manager’s name, use a variation of “Dear Hiring Manager.” This shows you’ve taken the time to research the company before applying and demonstrates your genuine enthusiasm for the opportunity.

2. Introduction

Lead your secretary cover letter with a strong introduction to convey your interest in the job and grab the attention of the hiring manager. Build your paragraph around one of your most impressive career achievements, preferably backed by an eye-catching number or metric. Be sure to highlight your expertise in administrative support, client communications, and calendar management, skills especially important for secretarial roles.

In the example below, the applicant highlights the impact of their administrative support on a doctor’s office. Showcasing hard data in a similar manner is a great way to bolster the impact of your achievements on your secretary cover letter.

I’m interested in applying for the medical secretary position with Miami Cancer Institute. During my time with Ormond Beach Oncology Associates, I coordinated with physicians, nurses, and office personnel to enhance patient flow, resulting in a 20% reduction in wait times and a 92% patient satisfaction rating. I can achieve similar results for your organization in this role.

3. Body paragraphs

In the body paragraphs of your secretary cover letter, highlight your qualifications and career achievements as a secretary. Start by mentioning something specific about the company’s culture, reputation, or mission statement and why you’re enthusiastic about the opportunity. Feature tangible examples of the value you bring as a secretary and administrative professional, emphasizing quantifiable results. Consider adding a list of bullet points to break up the text on the page and improve the readability of your document.

Notice how the candidate below leverages their administrative experience within the health care field. Clinical environments are often fast-paced and high-stress, and yet the secretary has consistently found ways to improve operational efficiency and patient satisfaction throughout their career. Emphasizing your proven track record of success is essential for building a stand-out secretary cover letter.

As a seasoned administrator with 12 years of experience providing efficient secretarial support in hospitals, I am drawn to OrthoBoston’s reputation for exceptional patient care. I would relish using my skills and experience to ensure seamless treatment pathways for your service users. Some of my recent achievements include:

- Streamlined the post-meeting administrative process to ensure swift follow-up on assignments, contributing to a departmental productivity increase of 26% in 2023

- Trained five new hires and identified opportunities to enhance performance and service quality, which supported a 10% increase in patient satisfaction

- Implemented a new patient scheduling system that freed up an average of five appointments per practitioner per week

4. Secretary skills and qualifications

Rather than simply listing key skills on your secretary cover letter, tactically incorporate keywords from the job posting into your paragraphs. Feature examples of you utilizing various administrative skill sets in professional business environments. Below, we’ve gathered a wide range of potential skills you can add to your secretary cover letter:

| Key Skills and Qualifications | |

|---|---|

| Calendar management | Communication |

| Confidentiality | Customer service |

| Data entry | Document management |

| Email correspondence | Filing and recordkeeping |

| Interpersonal skills | Meeting coordination |

| Multitasking | Office administration |

| Organization | Project management |

| Scheduling | Telephone etiquette |

| Time management | Transcription |

| Travel arrangements | |

5. Closing section

The conclusion of your secretary cover letter should feature a call to action (CTA) that encourages the hiring manager to bring you in for an interview. This displays your confidence and genuine enthusiasm for the opportunity. Be sure to thank the hiring manager for their time and consideration in the last sentence of the paragraph.

I look forward to scheduling an interview to tell you more about how my background as a medical secretary can help further enhance patient-care delivery at Miami Cancer Institute. Feel free to contact me via phone or email for any additional questions you may have on my background. Thank you for your time and consideration.

Best regards,

Aliya Jackson

Secretary Cover Letter Tips

1. feature your expertise in administrative support.

Secretarial positions require strong organizational and administrative skill sets. As you craft your cover letter, call out these qualifications using specific instances from your work history. In the example below, the candidate demonstrates their ability to manage calendars, correspondence, and documentation for a premier law firm. This helps to convey how their experience can help refine operations for potential employers:

- Provided administrative support to legal teams, drafted correspondence, coordinated client communications, managed calendars, and organized physical and electronic files to support multi-million dollar legal cases

- Maintained client and firm files, coordinated conference room meetings, purchased office supplies, and oversaw invoicing procedures

- Managed attorney calendars, scheduled client appointments, and verified court dates

2. Highlight your communication and client relations skills

As a secretary, you’ll be responsible for fielding inquiries and managing client communications on a daily basis. Hiring managers want to see how you’ve leveraged these skills throughout your career. In the example below, the applicant highlights their background interfacing with patients suffering from debilitating and life-threatening conditions, especially valuable when applying for secretarial positions in health care:

Miami Cancer Institute’s reputation for its comprehensive clinical standards is what excites me about this opportunity. Throughout my career as medical secretary, I’ve communicated with empathy and compassion while interfacing with patients suffering from debilitating and life-threatening health conditions. I can help your team continue to improve the patient experience based on my previous achievements:

3. Align your cover letter with the job description

Tailoring your cover letter towards individual job descriptions is the best way to maximize your chances of landing the interview. In addition to mentioning specifics about the organization’s reputation or culture, convey how your industry knowledge and experience make you a good fit for the role. Below, the candidate emphasizes their background working in the legal field, which sends a clear message they can adapt to the needs of prospective law firms:

Richardson and Stone Legal Associates’ reputation as a leading personal injury firm draws me to apply for this opportunity. During my time with Haden Law Group, I fielded inquiries from potential clients, drafted correspondence, and liaised with clients, defense counsel, and courtrooms. I can support legal operations for your firm based on my career achievements:

Secretary Text-Only Cover Letter Templates and Examples

Aliya Jackson Secretary | [email protected] | (123) 456-7890 | Miami, FL 12345 | LinkedIn

January 1, 2024

Pat Martin Senior Hiring Manager Miami Cancer Institute (987) 654-3210 patmartin@miamicancerinstitute,org

Dear Pat Martin:

Miami Cancer Institute’s reputation for its comprehensive clinical standards is what excites me about this opportunity . Throughout my career as a medical secretary, I’ve communicated with empathy and compassion while interfacing with patients suffering from debilitating and life-threatening health conditions. I can help your team continue to improve the patient experience based on my previous achievements:

- Fielded phone inquiries for new and existing patients, managed appointment scheduling, conducted new patient orientations, and handled electronic medical records

- Managed physician calendars, resolved scheduling conflicts, interfaced with diverse patient populations, and contributed to an organization-wide 92% patient satisfaction score

- Conducted patient scheduling, registration, and data entry for a medical office with over 250 patients, updated health records, and ensured compliance with HIPAA

Allison Rosenberg Secretary | [email protected] | (123) 456-7890 | San Diego, CA 12345 | LinkedIn

Hector Santos Senior Hiring Manager Richardson and Stone Legal Associates (987) 654-3210 [email protected]

Dear Mr. Santos:

I’m reaching out to apply for the secretary position with Richardson and Stone Legal Associates that I found on LinkedIn. As you can see from my resume, I have over five years of secretarial experience in established law firms. My expertise in administrative support and calendar management would be a strong asset to your team in this role.

Richardson and Stone Legal Associates’ reputation as a leading personal injury firm is what draws me to apply for this opportunity. At Haden Law Group, I fielded inquiries from potential clients, drafted correspondence, and liaised with clients, defense counsel, and courtrooms. I can support legal operations for your firm based on my career achievements:

I’d like to set up an interview to discuss how my experience as a secretary and legal assistant can provide value to your law firm. Feel free to contact me via phone or email at your convenience. I appreciate your time and consideration.

Allison Rosenberg

Kevin Morrison Secretary | [email protected] | (123) 456-7890 | Boston, MA 12345 | LinkedIn

Lori Taylor Senior Hiring Manager OrthoBoston (987) 654-3210 [email protected]

Dear Ms. Taylor,

During my time as the secretary for Providence Orthopedics, I overhauled my department’s data gathering protocols to successfully reduce pre-surgical file omissions by 98%. This project significantly improved the availability of crucial medical information and saved over 15 work hours per week. I look forward to leveraging my outstanding organizational skills as the pre-admissions department secretary at OrthoBoston.

As a seasoned administrator with 12 years of experience providing efficient secretarial support in hospitals, I am drawn to OrthoBoston’s reputation for exceptional patient care. I would relish utilizing my skills and experience to ensure seamless treatment pathways for your service users. Some of my recent achievements include:

I look forward to speaking with you further about how my secretarial experience within the health care field can help your organization continue to deliver exceptional patient care. You may contact me via phone or email at your convenience. Thank you for your time and consideration.

Kevin Morrison

Secretary Cover Letter FAQs

Why should i submit a secretary cover letter -.

Although most job applications won’t require a cover letter for secretary positions, including one is a great way to showcase your written communication skills and make a strong first impression on the reader. Because most candidates won’t be submitting a cover letter, taking the time to craft a customized document may actually help differentiate you from the competition during the job search.

How do I make my secretary cover letter stand out? -

To maximize the value of your cover letter, provide unique insights into who you are as a professional using more personalized language in comparison to the resume. Convey your story using key examples from your professional history. This will help send a clear message that you have the necessary qualifications for the role and that you’re a good fit for the company’s culture.

How long should my cover letter be? -

In most situations, a concise yet compelling cover letter will be more beneficial to your job application. Limit your cover letter to three or four paragraphs, keeping the reader’s focus on your most notable accomplishments. Secretary job descriptions are often generic, and omitting bland details will only make your document stronger.

Craft a new cover letter in minutes

Get the attention of hiring managers with a cover letter tailored to every job application.

Frank Hackett

Certified Professional Resume Writer (CPRW)

Frank Hackett is a professional resume writer and career consultant with over eight years of experience. As the lead editor at a boutique career consulting firm, Frank developed an innovative approach to resume writing that empowers job seekers to tell their professional stories. His approach involves creating accomplishment-driven documents that balance keyword optimization with personal branding. Frank is a Certified Professional Resume Writer (CPRW) with the Professional Association of Resume Writers and Career Coaches (PAWRCC).

Check Out Related Examples

Executive Assistant Cover Letter Examples and Templates

Medical Receptionist Cover Letter Examples and Templates

Receptionist Cover Letter Examples and Templates

Build a resume to enhance your career.

- Drop “To Whom It May Concern” for These Cover Letter Alternatives Learn More

- How To Describe Your Current Job Responsibilities Learn More

- Top 10 Soft Skills Employers Love Learn More

Essential Guides for Your Job Search

- How to Write a Resume Learn More

- How to Write a Cover Letter Learn More

- Thank You Note Examples Learn More

- Resignation Letter Examples Learn More

- Create a Cover Letter Now

- Create a Resume Now

- My Documents

- Examples of cover letters /

Executive Secretary

Executive Secretary Cover Letter

You have the skills and we have tricks on how to find amazing jobs. Get cover letters for over 900 professions.

- Svitlana Harkusha - Head Career Expert

How to create a good cover letter for an executive secretary: free tips and tricks

If you want to land a job interview, you better craft a proper cover letter. HRs and employers pay a lot of attention to it. Check out an executive secretary cover letter example below to see how we suggest you use the tips and tricks for writing one. Use the experience of applicants who have been in those shoes before you and apply it to your situation.

You have only one chance to make an impression. And it starts with your cover letter. Its visual presentation says a lot to the recruiter. So do your homework and pen out a nice document with the pleasing font, right format, and elegant layout.

Don’t go relaxed on it. If you don’t put forth an effort, it can end for you right there. Don’t go for sloppy work in terms of layout and formatting. Your role as an executive secretary is to pay attention to the details, so demonstrate it right away!

Even if you are an entry-level candidate, don’t be intimidated by a position. Pump up your cover letter with summer practice achievements and intern experience. Do you know the expression ‘fake it until you make it’? That is where you can apply it to yourself in case of insecurities.

Don’t go by the path of beating yourself up and acknowledging your weak sides right on the spot. If you have a degree, mention it. If you had an internship in a well-respected place, remember to put it in. You will not send the recruiter off the track but at least they will see that you are ready to learn.

Carrying out secretarial duties to executives requires you not only to answer phones, pull up documents and coordinate schedules but also to use perfect communication skills. Make sure you mention it in greater detail.

Don’t be afraid to sound personal and reveal yourself as a person with certain characteristics. Probably, it is not the time and place to put a joke in but you can definitely go outside of any generic description and show yourself not only as a specialist but as an individual too.

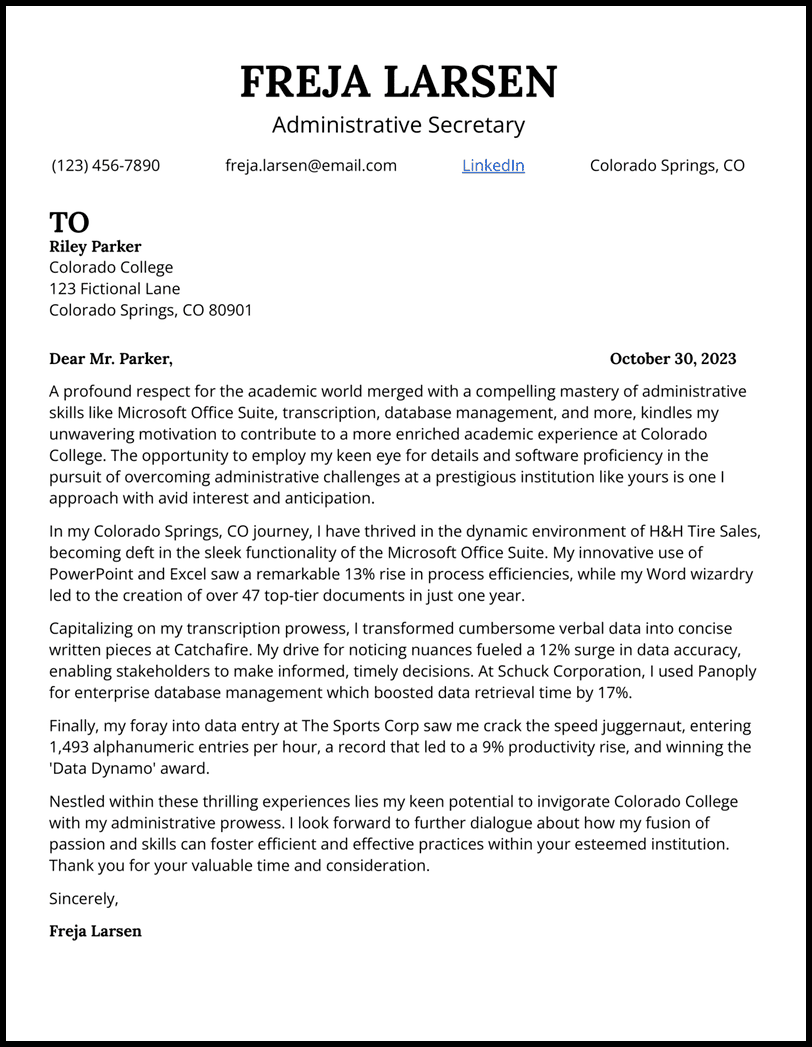

Sample cover letter for an executive secretary position

The most effective way to digest the tips is to see their practical application. We have used all the important tips of the above units into a single an executive secretary cover letter sample to demonstrate a winning document that can be created in GetCoverLetter editor.

Boris Johnson Executive Secretary 2 Downing Street 8779-250-918 / [email protected] Daniel Kanneman Recruiter “Slow Thinking Co.”

Dear Daniel, My enthusiasm for “Slow Thinking Co.” has been with me for decades, as I have a lot of respect for what the company does and its ethic policy. That is why I would love to have an opportunity to offer my modest skills to you.

As an MBA degree holder, I had a short summer internship at IBM Watson. As an office assistant, I carried out secretarial duties to a number of managers and employees. I learned to arrange appointments and meetings, use a filing system, prepare and distribute correspondence within the office, and other administrative tasks to keep the office run smoothly and the colleagues happy. However, most of all, I pride myself on my avid communication skills. I am able both to keep guests entertained with reasonable amount of small talk and be quiet and unobtrusive with the reticent colleagues.

Enclosed you will find my resume and letter of recommendation. I hope to hear from you soon and prove myself fit the position in person.

Sincerely, Boris.

This example is not commercial and has a demonstrative function only. If you need unique Cover Letter please proceed to our editor.

Do not waste on doubts the time that you can spend on composing your document.

How to save time on creating your cover letter for an executive secretary

Our Get Cover Letter editor will help you make the process easy and fast. How it works:

Fill in a simple questionnaire to provide the needed information about yourself.

Choose the design of your cover letter.

Print, email, or download your cover letter in PDF format.

Why the Get Cover Letter is the best solution

The GetCoverLetter editor is open to any goals of applicants. Whether it be a presentation of a craft professional with a great list of achievements or even an executive secretary without experience. Rest assured, the opportunities are equal for all the candidates.

Our creators will worry about which layout to choose for the executive secretary job application, so you don't have to.

We know how important format is, so we stick to a strong business writing style, so that all can be in your favor with your potential employer.

Our fast and easy online composer makes creating and editing a breeze. You can choose your skill and add personal info in no time.

All the above and other benefits of using our editor are only one click away.

Templates of the best an executive secretary cover letter designs

Any example of the document for an executive secretary has a precise design per the requirements of the company or the general rules of business correspondence. In any case, the selection of templates in our editor will meet any expectations.

Or choose any other template from our template gallery

Overall rating 4.3

Overall rating 4.5

Get Cover Letter customer’s reviews

“Such services as GetCoverLetter are god-sent gifts. I was very pleased with the end result, and let me tell you – the machine does it much better than I would ever do. It is quite weird and intimidating but I still use it every time I need it.”

“In today’s fast-paced time, people simply cannot afford to sit around fumbling with all that job application documentation. I have no patience for that. And I’m happy that I can go online and deal with it in a matter of minutes.”

“I pride myself on being an expert in my field of expertise. But penning out cover letters is something utterly different. An absolute genius came up with this builder. And I’m eternally thankful them for it!”

Frequently Asked Questions

The more unique the knowledge you get, the more space for new questions. Do not be affraid to miss some aspects of creating your excellent cover letter. Here we took into account the most popular doubts to save your time and arm you with basic information.

- What should my an executive secretary cover letter contain? The main purpose of a cover letter is to introduce yourself, mention the job you’re applying for, show that your skills and experience match the needed skills and experience for the job.

- How to properly introduce yourself in a cover letter? Greet the correct person to which your cover is intended for. Introduce yourself with enthusiasm.

- How many pages should my cover letter be? Your cover letter should only be a half a page to one full page. Your cover letter should be divided into three or four short paragraphs.

- Don't focus on yourself too much

- Don't share all the details of every job you've had

- Don't write a novel

You have finished your acquaintance with valuable tips and tricks. Now is the time to create your own perfect cover letter.

Other cover letters from this industry

Here is our simple way of how to write a cover letter. However, don’t limit yourself by your qualifications only. Check out the links below to see applications for other jobs. They may inspire you to add up to your cover letter too.

- Executive Director

- Executive Administrative Assistant

- Senior Executive Assistant

Secretary Cover Letter Example

Cover letter examples, cover letter guidelines, how to format an secretary cover letter, cover letter header, cover letter header examples for secretary, how to make your cover letter header stand out:, cover letter greeting, cover letter greeting examples for secretary, best cover letter greetings:, cover letter introduction, cover letter intro examples for secretary, how to make your cover letter intro stand out:, cover letter body, cover letter body examples for secretary, how to make your cover letter body stand out:, cover letter closing, cover letter closing paragraph examples for secretary, how to close your cover letter in a memorable way:, pair your cover letter with a foundational resume, key cover letter faqs for secretary.

You should start your Secretary cover letter by addressing the hiring manager directly, if their name is available. If not, use a professional greeting like "Dear Hiring Manager". Then, introduce yourself and state the position you're applying for. Make sure to express your enthusiasm for the role and briefly mention how your skills and experience make you a strong candidate. For example, "I am excited to apply for the Secretary position at your company. With my 5 years of experience in administrative roles and exceptional organizational skills, I am confident I can contribute effectively to your team." This sets a positive tone and immediately highlights your suitability for the role.

The best way for Secretaries to end a cover letter is by expressing gratitude for the reader's time and consideration, reiterating their interest in the role, and inviting further discussion. For example, "Thank you for considering my application. I am very interested in the Secretary position and believe my skills and experience make me a strong candidate. I look forward to the possibility of discussing my application with you further." This ending is professional, courteous, and shows enthusiasm for the role. It's also important to end with a formal closing such as "Sincerely" or "Best Regards," followed by your name. Remember, a cover letter is your chance to make a good first impression, so ensure it's well-written, concise, and free of errors.

Secretaries should include the following elements in their cover letter: 1. Contact Information: Your name, address, phone number, and email address should be at the top of the cover letter. If you're sending an email cover letter, this information can be included in your email signature. 2. Salutation: Address the hiring manager directly if you know their name. If not, use a general salutation like "Dear Hiring Manager." 3. Introduction: Start by introducing yourself and stating the position you're applying for. Mention where you found the job posting. 4. Relevant Skills and Experience: Highlight your skills and experiences that are directly relevant to the secretary position. This could include experience in office administration, proficiency in office software, excellent communication skills, and ability to manage multiple tasks or projects at once. 5. Achievements: Mention any achievements or accomplishments from your previous roles that demonstrate your ability to perform the job effectively. For example, if you implemented a new filing system that increased efficiency, or if you were praised for your exceptional customer service skills. 6. Knowledge about the Company: Show that you've done your research about the company and express why you're interested in working there. This shows your enthusiasm and commitment. 7. Closing: In your closing paragraph, thank the hiring manager for considering your application. Express your interest in discussing your qualifications further in an interview. 8. Signature: End with a professional closing like "Sincerely" or "Best regards," followed by your name. Remember, your cover letter should complement your resume, not duplicate it. It's your chance to tell a story about your experiences and skills, and to show your personality. Always proofread your cover letter before sending it to avoid any typos or errors.

Related Cover Letters for Secretary

Related resumes for secretary, try our ai cover letter generator.

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Example

An employer has to go through many cover letters; therefore, he utilizes the ‘Applicant Tracking System’ to find the most relevant cover letter. An Executive Secretary Cover Letter must make use of keywords relevant to the job expectation and are scattered throughout your cover letter.

The Executive Secretary Cover Letter Sample shown below has put together all the necessary information in your reference’s most understandable format.

- Cover Letters

- Office & Administrative

What to Include in a Executive Secretary Cover Letter?

Roles and responsibilities.

An Executive Secretary offers efficient administrative & clerical assistance to the management executives. His role includes the following responsibilities:

- Responding to incoming calls & messages .

- Keeping contact records and details.

- Organizing and scheduling meetings .

- Planning long-term schedules.

- Training newly employed members.

- Maintaining public relations.

Education & Skills

Executive secretary skills:.

- Impressive communication skills to handle incoming calls.

- Excellent decision maker to plan and arrange meetings.

- Outstanding coaching skills to train new hires.

- Practical interpersonal skills to maintain public relations.

- Capable of working under pressure and uphold with deadlines.

- Detail-oriented to record and relay the messages to the concerned person.

Executive Secretary Educational Requirements:

- Graduation in Business Administration (preferred).

- Executive support work experience (preferred).

- Deep understanding of secretarial and administrative fundamentals.

- Working knowledge of bookkeeping and databases.

- Proficiency at MS Office and similar software (required).

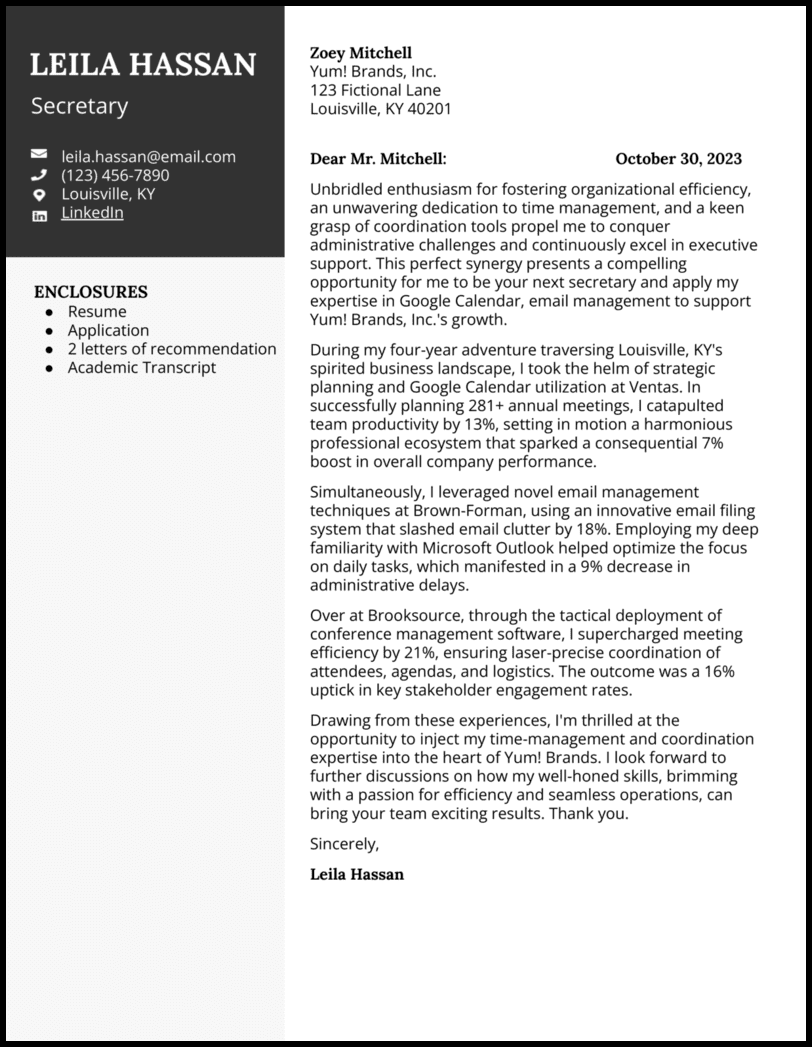

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Example (Text Version)

Dear Mr./Ms.,

I am writing this application to show my interest in the Executive Secretary’s available position that has been promoted on Indeed.com. I was thrilled to know the job requirements as they perfectly matched my skill set and professional background. I have been performing the following tasks in the present company:

- Conduct precise research.

- Arrange/Organize meetings & conferences.

- Handle calls, emails, and faxes.

- Operate office equipment.

- Take minutes of meetings/dictation.

- Revise reports & documents thoroughly.

- Create accurate reports and presentations.

- Arrange travel and accommodation, maintain the calendar.

Therefore, I believe I am all set to channel my expertise as Executive Secretary for your esteemed organization. My resume will indicate a brief of my education and employment background. I am looking forward to discussing my value for your organization. Thank you for taking the time to read my letter.

Sincerely, [Your Name]

Highlight your unique competencies and relevant coursework and your volunteer work to make the best case for your candidacy. Craft a stellar resume pitched with the most substantial outcomes you can bring in conjunction with the opportunity. Our Executive Secretary Resume Sample has covered all the required details that are needed for the particular position.

Customize Executive Secretary Cover Letter

Get hired faster with our free cover letter template designed to land you the perfect position.

Related Office & Administrative Cover Letters

Executive Secretary Cover Letter Examples