- In the News

- Impact Videos and Stories

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Policies, Disclosures and Reports

Confidentiality in the Age of AIDS: A Case Study in Clinical Ethics

Print this case study here: Case Study – Confidentiality in the Age of AIDS

The Journal of Clinical Ethics, Fall 1993

Martin L Smith, STD, is an Associated in the Department of Bioethics, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, Ohio.

Kevin P Martin, MD is a Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist in the Department of Mental Health, Kaiser Permanente, Cleveland.

INTRODUCTION

AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome), now in pandemic proportions, presents formidable challenges to health-care professionals. The human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and its related diseases have also raised a number of thorny ethical questions about government and social policy, health-care delivery systems, and the very nature of the physician-patient relationship. This article presents the case of an HIV-positive patient who presented the treating physician, a psychiatrist, with an ethical dilemma. We provide the details of the case, identify the ethical issues it raises, and examine the ethical principles involved. Finally, we present a case analysis that supports the physician’s decision. Our process of ethical analysis and decision making is a type of casuistry,1 which involves examining the circumstances and details of the case, considering analogous cases, determining which maxim(s) should rule the case and to what extent, and weighing accumulated arguments and considerations for the options that have been identified. The goal of this method is to arrive at a reasonable, prudent moral judgement leading to action.

The patient, Seth, is a 32-year-old, HIV-positive, gay, white male whose psychiatric social worker had referred him to a community-mental-health-center psychiatrist for evaluation. He had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that went back several years. He had been functioning well for the last two years as an outpatient on antipsychotic medications and was working full time, socializing actively, and sharing an apartment with a female roommate.

The social worker described a gradual deterioration over several months. Seth had become less compliant with his medication and with his appointments at the mental-health center, had lost his job, had been asked to leave his apartment, and was living on the streets. He was described as increasingly disorganized and paranoid. His behavior was increasingly inappropriate, and he had only limited insight into his condition.

On examination, Seth was thin, casually dressed, slightly disheveled, and with poor hygiene. His speech was spontaneous, not pressured, and loose with occasional blocking. [That is, he spoke spontaneously, he could be interrupted, and his speech was unfocused with occasional interruption of thought sequence.] His psychomotor activity was labile [unstable]. His affect was cheerful and inappropriately seductive, and he described his mood as ”mellow.” He denied having hallucinations, systematized delusions and suicidal or homicidal ideation. He admitted having ideas of reference [incorrect interpretation of casual incidents and external events as having direct reference to himself], was clearly paranoid, and at times appeared to be internally stimulated. He made statements such as: “They’re blaming me for everything,” and “I’m scared all the time,” although he was too guarded or disorganized to provide more detail. His cognitive functioning was impaired, and testing was difficult given his distracted, disorganized state. His judgement was significantly impaired, and his insight was quite limited.

At the time of the evaluation, Seth indiscriminately revealed his HIV-positive status to the staff and other patients. He claimed he had been HIV positive for five years, and he denied that he had developed any symptoms of disease or taken any HIV-related medications. He was not considered reliable, and the staff sought confirmation. After he provided the location and approximate date of his most recent HIV test, the physician confirmed that the patient had been HIV positive at least since the test, about a year earlier.

When asked, Seth stated that the was not currently in a relationship. He appeared to be disorganized and could not name his most recent sexual partner(s). He could not remember whether he had been practicing safer sex and whether he had informed his partners of his HIV positive status.

In addition to the information he obtained during the evaluation, the psychiatrist, by chance, had limited personal knowledge of the patient. Through his own involvement as a member of the local gay community, the psychiatrist had briefly met the patient twice – once while attending an open discussion at the lesbian-gay community center, and later, at a worship service in a predominantly lesbian-gay church. The physician recalled that Seth had seemed to be functioning quite adequately, at least superficially. He was somewhat indiscriminately flirtatious, his behavior was otherwise appropriate, and he did not appear to be psychotic or disorganized in his thinking. He was not overtly paranoid and did not publicly reveal his HIV-positive status.

Through the church, the psychiatrist had also become acquainted with Maxwell and Philip, who were partners in a primary sexual relationship. Before Seth’s decompensation [deterioration of existing defenses, leading to an exacerbation of pathologic behavior], but after he was known to have tested HIV positive, Seth and Maxwell had been lovers. Maxwell left Philip and moved in with Seth for about two months, but then left Seth and returned to Philip around the time of Seth’s decompensation.

The psychiatrist was not privy to details of Maxwell and Seth’s or Maxwell and Philip’s sexual practices. He did not know of the HIV status of Maxwell or Philip, or whether either had ever been tested. In addition, he was unaware of whether Maxwell or Philip know of Seth’s HIVpositive status at the time of Maxwell’s relationship with Seth, or at any time thereafter. During the evaluation, Seth did not recall having met the psychiatrist, nor did he mention his relationship with Maxwell.

Seth agreed to enter a crisis stabilization unit and to resume treatment with antipsychotic medications. Free to come and go at will during daylight hours, he left the unit on day two, failed to return, and was lost to follow-up. His mental status had not changed significantly before he left the crisis unit.

In this case, the physician’s duty to maintain physician-patient confidentiality conflicts with his duty as a psychiatrist to warn third parties at risk. Clearly, a patient’s status as HIV positive is a matter of confidentiality between doctor and patient. Just as clear is the risk for third parties to whom the patient may pass the virus via sexual intercourse. It is unknown whether everyone infected with HIV will develop AIDS, or how many months or years may intervene between infection and the appearance of full-blown AIDS. However, once AIDS develops it is always fatal.2 Therefore, there is a potentially lethal risk to a person having intercourse, particularly without employing safer sex-practices, with another infected with the HIV virus.

This ethical conflict raises two questions. Is it permissible to violate confidentiality to warn a third party at risk? Is there a duty to violate confidentiality to warn a third party at risk? The potential benefit to the third parties must be considered, as well as the strength of the principle of confidentiality in the patient-physician relationship. There is also wider societal consideration as to how breaches of confidentiality, even for good reasons, will affect voluntary testing and seeking of prophylactic treatment by HIV-positive persons. This societal consideration must be weighed against the benefit to the individual third party of knowing the risk and then choosing to be tested and treated and choosing to be tested and treated and choosing to take precautions against infecting others.

In this case, another issue arises from the fact that the physicians of at least one third party who may have been placed at risk possibly without his knowledge, was obtained through personal knowledge, outside the professional relationship. Is it appropriate to bring this information into the clinical setting, particularly because it is so central to the primary ethical issue? Does the physician have an obligation to act on this information?

Finally, two additional sets of issues complicate this case. First, the patient’s decompensation and disappearance necessitate the physician’s choosing a course of action without patient consent or cooperation, and with patient-supplied information that is incomplete and probably unreliable. Second, a breach of confidentiality could greatly damage the physician’s position as a psychiatrist and a trusted member of the gay community, offering assistance directly to some and referral to many others. Given these issues, what should the physician do?

BACKGROUND DISCUSSION

Some background information will be useful in analyzing the ethical issues of the case. This information includes basic ethical values and norms, and legal mandates and opinions about confidentiality, the duty to warn, and HIV/AIDS reporting.

Whether privacy is viewed as a derivative value from the principle of autonomy or as a fundamental universal need with its own nature and importance,3 privacy, and the associated issue of confidentiality, is generally accepted as essential to the relationship between physician and patient. The purpose of confidentiality is to prevent unauthorized persons from learning information shared in confidence.4 Stated more positively, confidentiality promotes the free flow of communication between doctor and patient, thereby encouraging patient disclosure, which in turn should lead to more accurate diagnosis, better patient education, and more effective treatment.

The Hippocratic Oath is evidence of the long-standing tradition of confidentiality in Western though: “What I may see or hear in the course of treatment… I will keep to myself, holding such things shameful to be spoken about.” More recently, the American Medical Association,6 the American Psychiatric Association,7 the American College of Physicians, and the Infectious Diseases Society of America8 have reaffirmed the right of privacy and confidentiality, specifically for HIV-positive patients. Without the informed consent of the patient, physicians should not disclose information about their patient. The Center for Disease Control also recommends that patient confidentiality be maintained, because the organization believes that a successful response to the HIV epidemic depend on research and on the voluntary cooperation of infected persons.9That is, the interests of society seem best served if the trust and cooperation of those at greatest risk can be obtained and maintained.10

Within the complexities of clinical care, should patient confidentiality be regarded as absolute, never to be breached under any circumstances (as claimed by the World Medical Association in its 1949 International Code of Medical Ethics11)? Or should confidentiality be regarded as a prima facie duty? (That is, should it be binding on all occasions unless it is in conflict with equal or higher duties?12)

Most commentators and codes conclude that patient confidentiality is not absolute and, therefore, it could – and even should – be overridden under come conditions.13 In other words, in a specific situation in which patient confidentiality is one value at stake, the health-care provider’s actual duty is determined by weighing the various competing prima facie duties and corresponding values, including confidentiality. (As might be expected, not all authors accept this conditional view of confidentiality and argue for its absolute quality.14) There is less unanimity about the circumstances under which patient confidentiality can be justifiably breached. More specifically for HIV-positive patients, the controversy revolves around the premise that some circumstances might create a duty to warn endangered third parties, even at the expense of confidentiality. The potential for harm to HIV-positive patients through breaches of confidentiality is great. Discrimination, isolation, hospitality, and stigmatization are all too real for these patients when their HIV-positive status has become known to others.15 Further, societal harm is possible if these patients – who might ordinarily seek medical attention voluntarily – refrain from doing so, knowing that professional breaches of confidentiality may ensue. Without ignoring this potential societal harm, the majority opinion of professional codes and of ethical and legal experts16 foresee the possibility of a duty to warn through discrete disclosure, especially if others are in clear and imminent danger if the patient cannot be persuaded to change hi behaviors or to notify those at risk of exposure.

Public health regulations often reflect the same conclusion – that confidentiality can be compromised under certain circumstances – and therefore mandate reporting HIV-positive and AIDS patients to public health authorities. Patient confidentiality is not to be upheld so strictly that it obviates an ethically justified (and usually legally mandated) duty to report such cases to authorized health agencies. Those who support such public policies view society’s right to promote its health and safety, and the need for accurate epidemiological information, to be at least as important as an individual’s right to privacy and confidentiality.

In trying to balance patient confidentiality with other professional values, the California Supreme Court decision in Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California17 has become a guideline for other courts and health-care professionals (although technically this decision applies to only one state and specifically addresses a unique set of circumstances). In this famous and controversial case heard before the California Supreme Court in 1976, the majority opinion held that the duty of confidentiality in psychotherapy is outweighed by the duty to protect an intended victim from a serious danger of violence. The court explained the legal obligation to protect and the potential duty to warn as follows:

When a therapist determines, or pursuant to the standards of his profession should determine that his patient presents a serious danger of violence to another, he incurs an obligation to use reasonable care to protect the intended victim against such danger. The discharge of this duty may require the therapist to take one or more various steps, depending upon the nature of the case. Thus, it may call for him to warn the intended victim or others likely to apprise the victim of the danger, to notify the police, or to take whatever steps are reasonably necessary under the circumstances.18

Regarding the limits placed on confidentiality under these conditions, the court stated: “The protective privilege ends where the public peril begins.” This “Tarasoff Tightrope” identifies for the professional the dual duties of promoting the well-being and interests of the patient and protecting public and private safety.

Given the general jurisdictional autonomy of each state, the duty to protect and the potential duty to warn as adopted in California has been applied differently in different states.20 Although most commentators assume that Tarasoff is relevant for sorting out the issue of confidentiality relative to HIV-positive patients, this assumption is not universally accepted.21

Without a state statute or court case that specifically addresses the tension between patient confidentiality and the right of others to know whether they may have been exposed to HIV infection, and given the conundrum of legal principles relating to AIDS confidentiality, it is unclear as to who must be warned and under what circumstances.22 This lack of clarity is in indication that, in practice, the professional duty to warn is not absolute but always conditioned by the circumstances of the case (that is, the duty to warn is a prima facie value).

The above paragraphs describe an emerging consensus among health-care professionals who face confidentiality dilemmas, although universal agreement has not been fully achieved. Further, this emerging consensus and its contributing principles by no means provide easy answers to ethical quandaries. Each case, with its own specific set of relevant circumstances, must be analyzed and judged individually. Such an analysis of the presented case now follows.

AN ANALYSIS

Seth’s case, perceived as a dilemma by the psychiatrist, could be brushed aside easily if the information obtained outside the therapeutic relationship was simply ignored. But the lethality of HIV infection makes it difficult to dismiss the information either as irrelevant or inadmissible for serious consideration. Had the information been obtained by unethical means (for example, by coercion or deception), a stronger justification for not using the information might be made. Such is not the situation. Without reason to ignore this information, the psychiatrist must incorporate this “data of happenstance” into his decision. To do so, of course, places him precisely at the crossroads of the dilemma: to uphold confidentiality, to warn the third party, or to create an option that supports the values behind these apparently conflicting duties.

Several factors ethically support both a breach of confidentiality and the physician’s duty to warn and protect the third party: the emerging professional consensus that confidentiality is not absolute; the known identity of a third party who stands in harm’s way; the risk to unknown and unidentified sexual partners of the third party; and the deadliness of AIDS. Such a combination of factors is what the professional statements noted above23 have tried to address in their allowance for limits to patient confidentiality. In this case, the risk to the known third party has already been established, but other people may be at risk, including sexual partners of the patient and those of the third party. Individuals infected and unaware will not benefit from prophylactic therapies.

An additional reason for the psychiatrist to warn the third part is the patient’s mental status, which probably renders him incapable of informing his sexual partner(s) or of consenting to the physician’s informing them. On admission, he was not able to name his partner(s), and he was lost to follow-up without significant change in his mental status. Without the decision-making capacity of the likelihood of action on the part of the patient, any warning to the third party would have to come from the physician or through public health officials notified by the physician.

But the duty to warn, incidental information, and mental status are not the only factors that need to be considered here. Patients are subject to the risks of discrimination when their HIV status is disclosed. But for a patient who has indiscriminately revealed his own HIV-positive status, the physician’s contribution to this risk of discrimination through discreet disclosure to one person may be minimal.

Also, to be considered is the societal risk that testing and prophylactic treatment of HIV-positive persons will decrease if confidentiality is not upheld. Members of the lesbian and gay community are often mistrusting of medical and mental health professionals,24 perhaps with valid reason. Mistrust, fear, and nonparticipation in voluntary programs may increase if confidentiality cannot be assured. Persons will be less likely to come forward voluntarily for education, testing, or other assistance if their well-being is threatened as a result. In Tarasoff, the court declared that protective privilege ends where social peril begins. In this case, overriding the protective privilege of the individual could lead to greater societal peril. Trust in this physician by members of the lesbian and gay community benefits individuals and the community as a whole, by improving access to medical and mental health services. A breach of confidentiality, if it became known, could damage this trust, as well as the physician’s reputation, reducing his professional contributions to the community. This professional loss would be significant.

Also, to be considered is the general knowledge of the higher risk among gay and bisexual men for HIV infection, as well as the information in the gay community as to what constitutes high risk behavior and what precautions can decrease risk of infection. Thus, we can reasonably assume that a gay or bisexual male is already aware of his risk and that of his sexual partner(s) for carrying the HIV virus. Warning a probably knowledgeable third party about the HIV-positive status may be of little benefit to the third party, while it risks the greater individual, societal, and professional harms discussed above. Regarding the risk to unknown sexual partners of the patient, whatever their number, the physician is powerless to change their fate precisely because they are unknown to him.

The duty to maintain patient confidentiality and the duty to warn third parties at risk can both be viewed as prima facie duties. In clinical situations such as the one described here, when one duty must be weighed against another to arrive at an ethically supportable solution, the weighing should take place only in the context of the given case. In this case, we found no solution that upholds all the duties; thus, a choice must be made between the two duties.

We submit that, although there is support for the physician to warn the third party, there is greater support for upholding confidentiality in this case. The individual risk of discriminatory harm from disclosure is possible, although admittedly small. Further, it is reasonable to presume the third party’s awareness of his risk and of the risk to his sexual partner(s) of carrying the HIV virus, and thus, his awareness of the need for appropriate precautions.

Even more persuasive is the peril to the local gay community and the wider society if a breach of confidentiality increases mistrust of the healthcare system and decreases the effectiveness of this particular psychiatrist to provide quality professional care. In this case, the confidentiality of the physician-patient relationship should be maintained.

What has been presented here can serve as a model for ethical decision making within the complexities of clinical care. As cases and their accompanying ethical questions arise, the details of each case should be gathered. Any tendency to label the case prematurely as a particular type (for example, a duty-to-warn case) should be resisted. Such a label can divert attention from relevant details that make each case unique. In examining the facts of the case and judging their significance, the values and duties at stake can be identified. If necessary and practical, background material and analogous cases should be researched. Ethical dilemmas present persons with hard choices. While several solutions may have some ethical support, few can be labeled as perfect solutions. Often, choosing one solution over another leaves behind an ethically significant value and regrettably may even produce harm. The circumstances described here presented the psychiatrist with a hard choice and no easy answer. We have suggested an ethically supported solution, but we found no perfect solution for the dilemma.

1. A.R. Jonsen, “Casuistry as Methodology in Clinical Ethics,” Theoretical Medicine 12 (1991): 295-307. 2. J.W. Curran, H.W. Jaffee, A.M. Hardy, et al., “Epidemiology of HIV Infection and AIDS in the United States,” Science 239 (1988): 610-16. 3. T.L. Beauchamp and J.F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983). 4. W.J. Winslade, “Confidentiality,” in Encyclopedia of Bioethics, ed. W.T. Reich (New York: Free Press, 1978). 5. L. Walters, “Ethical Aspects of Medical Confidentiality,” in Contemporary Issues in Bioethics,3rd edition, ed. T.L. Beauchamp and L. Walters (Belmont, Calif.: Wadsworth, 1989). 6. Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association, “Ethical Issues Involved in the Growing AIDS Crisis,” Journal of the American Medical Association 259 (1988): 1360-61. 7. American Psychiatry Association, “AIDS Policy: Confidentiality and Disclosure,” American Journal of Psychiatry 145 (1988): 541-42. 8. Health and Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians, and lnfectious Diseases Society of America, “A quired Immunodeficiency Syndrome,” Annals of Internal Medicine 104 (1986): 575-81. 9. Centers for Disease Control, “Additional Recommendations to Reduce Sexual and Drug-Related Transmission of Human T-Lymphotropic Virus Type I I1/L y mph adenopathy-Associated Virus,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 35 (1986a): 152-55. 10. R. Gillan, “AIDS and Medical Confidentiality,” in Contemporary lssues in Bioethics. Code of Ethics, 1949 World Medical Association,” in Encyclopedia of Bioethics. 11. W.O. Ross, The Foundations of Ethics (Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1939). 12. Beauchamp and Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics; Winslade, “Confidentiality”; Walters, “Ethical Aspects of Medical Confidentiality”; AMA, “Report on Ethical Issues”; APA, “AIDS Policy”; American College of Physicians and Infectious Diseases Society of America, “Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome”; S. Bok, “The Limits of Confidentiality,” Hastings Center Re port 13 (February 1983): 24- 31; H.E. Emson, “Confidentiality: A Modified Value,” Journal of Medical Ethics 14 (1988): 87-90. 13. M.H. Kottow, “Medical Confidentiality: An Intransigent and Absolute Obligation,” Journal of Medical Ethics 12 (1986):117-22. 14. R.J. Blendon and K. Donelan, “Discrimination against People with AIDS,” New England Journal of Medicine 319 (1988): 1022-26; L.O. Gostin, “The AIDS Litigation Project: A National Review of Court and Human Rights Commission Decisions, Part II: Dis crimination,” Journal of American Medical Association 263 (1990): 2086-93. 15. G.J. Annas, “Medicolegal Di lemma: The HIV-Positive Patient Who Won’t Tell the Spouse,” Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality 21 (1987):16; T.A. Brennan, “AIDS and the Limits of Confidentiality: The Physician’s Duty to Warn. Contacts of Seropositive Individuals,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 4 (1989): 242-46: B.M. Dickens, “Legal Limits of AIDS, Confidentiality,” Journal of the American Medical Assoclarion 259 (1988):3449-?1; S.L. Lentz. ”Confidentiality and lnformed Consent and the Acquired Immunodeficiency. Syndro111e. Epidemic,” . Archives of Pathology, & Laboratory Medicine 114 (1990):304 8; D. Seiden, “HIV ·Seropositive Patients and Confidentiality,” Clinical Ethics Report (1987): 1-8H.Zomina, “Warning Third 16. Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 11Cat.3d 425,551 P 2d ht (1,976) 17. Ibid. 18. R.D. Mackay, “Dangerous. Patients: Third Party Safety and Psychiatrists’ Duties: Walking the Tarasoff Tightrope,” Medicine, Science & the Law 3Q (1990): 52-56, 19. LA. Gray and A.R. Harding, “Confidentiality Limits with Clients Who Have the AIDS Virus,” Journal of Counseling and Development 6 (1988):219-23. 20. S. Perry, “Warning Third ‘Parties at Risk of AIDS: APA’s Policy is a Barrier to Treatment,” Hospital and Community Psychiatry 40 {1989):’ i5.8-6I. 21. L.O Gostin, The AIDS Litigation Project: A National Review of Court and Human Rights Commission Decisions. Part 1: The Social Impact of AIDS,” Journal of the American Medical Association 263 (1990), ‘961-7Q 22. AMA; “Report on Ethical Issues”; APA, “AIDS Policy”; American College of Physics and Infectious Diseases Society of America” Acquired lmmunodeficiency Syndrome.” 23. L. Dardick and KE Grady, “Openness between·:Gay Persons and Health Professionals,” Annals of Internal Medicine 93 -(1 80): 115-.19; T.A. DeCrescenzo, Homophobia: A Study of the Attitudes of Mental Health Professionals toward Homosexuality. Journal of Social Work and Homosexuality 2 (198):.84): 115-36.

Print this case study here: Case Study – Gathering Information and Casuistic Analysis

Gathering Information and Casuistic Analysis

Journal of Clinical Ethics By Athena Beldecos and Robert M. Arnold

Athena Beldecos is a graduate student in medical ethics in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Pittsburgh.

Robert M. Arnold, MD is an Assistant Professor of Medicine, and the Associate Director for Education, Center for Medical Ethics, University of Pittsburgh.

In their article, “Confidentiality in the Age of AIDS,” Martin L. Smith and Kevin P. Martin present a complex case in clinical ethics. Their analysis examines a physician’s quandary when treating a mentally incompetent HIV-positive patient: whether to uphold physician-patient confidentiality or to violate this confidentiality by warning a third party. Out critique focuses on the way the problem is conceptualized and the analytic methods used to resolve the case, rather than on the solution itself. We believe that several problems in the authors’ analysis arise from a misinterpretation of the casuistic method. Furthermore, we argue that Smith and Martin present a case that is insufficiently detailed, thereby precluding the identification of all of the moral problems in the case and the development of creature solutions to the problem(s) identified. We note several reasons why there is a need to gather more information prior to determining the appropriate ethical response. Finally, we suggest ways in which similar problems in clinical ethics might be avoided in the future.

IS THIS CASUISTRY?

The authors conceive of their “process of ethical analysis and decision making” as a “type of casuistry.” Although we agree that casuistry, as outlined by A.R. Josen,1 is a potentially fruitful technique for practical ethical decision making, we believe that certain essential features of such casuistic reasoning are not clearly present in Smith and Martin’s analysis.

The power and scope of casuistry are derived not only from attention to details and careful identification of circumstances in the presentation of individual cases, but – more importantly – from the process of case comparison. Using this method, a case under moral consideration is situated in a family of related cases, whereby the casuist examines the similarities and differences between the cases at hand. The context of an individual case and how its conflicting maxims appear within that particular context are the raw materials of the case-comparison method. The relative weight of conflicting maxims in an individual case is ascertained by comparison to analogous cases. With casuistry, moral judgement does not involve a more traditional retreat to the weighing of conflicting duties or general principles. Rather, moral guidance is provided by an ever-growing body of paradigm cases that represent unambiguous instances in which moral consensus is easily obtained. It is crucial that the casuist place the case under consideration in its proper taxonomic context(s) and that she or he identify the most appropriate paradigm, whether it be real or hypothetical.

The authors do identify a paradigm case, but their analysis departs from casuistry on several interrelated points. The authors do not proceed by analogical reasoning. Had they done so, they might have discovered that their chosen paradigm is inappropriate, due to significant dissimilarities with Seth’s case. Finally, their insufficiently detailed case precludes a thorough measurement of the similarities and differences between the cases at hand. For it is in the details that an individual case may differ from a paradigm case.

The authors’ analytic method has more in common with principle-based ethics2 than casuistry. They do not use a variety of similarly situated cases to point out and balance the relevant moral maxims instead, they extract the conflicting duties and principles from their paradigm, the Tarasoff case,3 and apply them directly to Seth’s case. The authors weigh one prima facie duty “against another to arrive at an ethically supportable solution.” Furthermore, the weighing takes place “only in the context of the given case.” Thus, case comparison, an intrinsic element of casuistry, is not performed. Instead, the authors’ major goal seems to be finding and applying a sufficiently modified principle regarding confidentiality to resolve the case at hand.

WHY TARASOFF IS PROBLEMATIC AS A PARADIGM CASE

By using Tarasoff as a paradigm case in their analysis, Smith and Martin situate their case in the family of “duty-to-warn” (prevention-of-harm) cases. It is reasonable that they identify this particular taxonomy as a starting point for their analysis. However, they do not test the appropriateness of the paradigm by systematically comparing and contrasting it with Seth’s case. The authors note the uniqueness of the circumstances of the Tarasoff case and its limited applicability but nonetheless proceed to use it as a paradigm. Casuistry, however, seeks closest-match paradigms. The use of analogical reasoning would have illuminated the similarities and differences between the two cases and would have helped the authors to determine which morally relevant features a paradigm case should minimally share with its analogous cases.

In the Tarasoff case, the court held that a psychotherapist, to whom a patient had confided a murderous intent, had a duty to protect the intended victim from harm.4 This duty includes warning the third party at risk, among other interventions. The unique circumstances of Tarasoff include the imminence of fatal harm to an identified, yet unsuspecting, individual. Although the authors are correct in noting the precedent-setting value of Tarasoff, the dissimilarities between Tarasoff and Seth’s case are so numerous as to suggest the selection of another paradigm.

First, a critical aspect in Tarasoff is the prevention of future fatal harm. Based on the circumstances of the case, there is no evidence of preventable fatal harm to Maxwell. For this condition to be satisfied, the psychiatrist would have to be assured of Maxwell’s seronegativity and have evidence of a current or an intended sexual relationship between Maxwell and Seth. The preventable harm to Maxwell consists of not allowing him the opportunity to institute early anti-viral therapy or to reconsider his life goals in the face of a fatal disease. A casuist would need to assess, using a series of cases, the moral difference between the fatal harm in Tarasoff and the lesser harms in the case of Seth.

Second, Tarasoff involves a person maliciously intending to harm another person. However, there is no evidence suggesting that Seth intended to harm Maxwell. Here, a casuist might begin the analysis using a paradigm case in which a physician is aware of his HIV-positive patient’s malicious intention to infect a third party from that point, one could progressively change the variables of the case to approach the degree of moral ambiguity and complexity shown in Seth’s case. This process would culminate in a case involving sexual relationship between a patient and his partner.

Third, the notion of harm with respect to HIV transmission is quite different from the harm to be prevented in Tarasoff . One might argue that fatal harm to others is averted by informing Maxwell of his risk for HIV positivity. He can subsequently alter his sexual practices and, thus, prevent the future spread of the virus. Herein lies the problem. In Tarasoff the person warned of the harm is also the person at risk of being harmed. In the case under discussion, however, warning Maxwell might prevent harm to other, yet unnamed individuals. A case analogous to Seth’s should describe a situation in which the possible harm has already occurred and the future harm to be avoided consists of preventing future transmission. An analogous case might involve issues of confidentiality in regard to the (vertical) transmission of a fatal genetic disease that manifests itself after sexual maturity. Imagine, for example, a young man afflicted with a severe and incurable genetic disease who has proceeded to start a family without disclosing his genetic status to his wife. Does his personal physician have a duty to uphold confidentiality in this case, or should he notify the spouse so that she can make informed reproductive decisions?

Fourth, in Tarasoff , the victim was presumably unaware of the intended harm. In Seth’s case, one can argue that Maxwell knows (or can be reasonably expected to know) the potential risk of having sexual relations with a homosexual. The authors mention this factor but do not provide a way to assess its importance. To test the importance of this morally relevant fact, a series of cases in which the third party is more (or less) responsible for knowing about the possibility of risk could be used for comparison. For example, how would our intuitions about physician disclosure in this case differ if Seth were a bisexual male who did not inform his wife of his unprotected extramarital affairs with gay and bisexual men?

Fifth, Seth was reported to have publicly announced his HIV-positive status, whereas the patient in Tarasoff disclosed his intent to kill within a protected doctor-patient relationship. Does the fact that “Seth indiscriminately revealed his HIV-positive status to the staff and other patients” at a community-mental-health-center make it easier for the psychiatrist to justify a violation of confidentiality in the name of protecting potential victims? Unfortunately, there is insufficient information to determine whether Seth’s public disclosure qualifies as a fair warning to potential victims and sanctions a violation of confidentiality. This point is potentially an important difference between Tarasoff and Seth’s case. The authors, however, would need to gather additional information concerning the circumstances of Seth’s public disclosures (when they began, to whom they were addressed, and so forth) before evaluating the weight of this morally relevant feature by comparison to a similar case.

Sixth, Tarasoff does not address the issue of how the duty to uphold confidentiality might be affected when a patient’s mental competence is in question. Seth’s case involves a mentally incompetent patient presumed to be “incapable of informing his sexual partner(s) [of his HIV positivity] or of consenting to the physician’s informing them.” The circumstances of this case raise the question: Does Seth’s physician have the same obligation to respect his patient’s confidences as he would have if Seth were a mentally competent adult patient? Central to this analysis is an understanding of how the underlying justifications for respecting the confidences of incompetent patients might differ from those of competent patients. Although the authors briefly discuss the implications of Seth’s impaired mental status, they could have profitably expanded their analysis of the ethical significance of a patient’s competency in regard to the physician’s duty to maintain confidentiality. The authors neglect to discuss, for example, how the selection of a surrogate to speak on Seth’s behalf might influence the case’s resolution.

Identifying which should be the determining factor(s) in deciding Seth’s case is a difficult moral problem. However, the first step is any casuistic analysis is to determine where the case fits in relation to other cases. Without this basic first step, it is too easy to neglect factors that may be critical in determining the proper course of action or to reply upon ad hoc, intuitive decisions.

THE NEED FOR A RICHLY DETAILED CASE

The casuistic method to which Smith and Martin supposedly subscribe, demands attention to the context of the particular case at hand, so that it may be compared to and contrasted with paradigm cases in which the ethical analysis is clear. A casuist needs sufficiently detailed information to be able to identify all of the moral issues and, thereby, situate an individual case in its appropriate taxonomy.

In Seth’s case, the authors seem to decide prematurely on the ethical issue, inappropriately hindering the search for future data. In the rush to identify and resolve the presumed ethical conflict, the ethicist may neglect to collect critical information.5 Without adequate information, the ethicist is unable to determine accurately what kind of case it is. While obtaining more information might be less interesting than theoretical analysis, often the most prudent course of action is to gather more information from the sources available in order to clarify and embellish the initial facts. Prior to leading the psychiatrist through a philosophical analysis of how to resolve the conflict between the duty to warn and the duty to uphold confidentiality, the authors should have urged the psychiatrist to obtain more information.

It is difficult, for example, to weigh the impact of Seth’s mental incompetency against the duty to maintain confidentiality because of a lack of sufficient information. Information regarding the severity of Seth’s mental illness and the chances of its reversibility would be useful in determining whether Seth should be viewed as only temporarily or permanently incompetent. If Seth is incompetent, it is not clear who should assess the harm done to Seth by a breach of confidentiality. We know too little about Seth’s life to determine who would most appropriately serve as his surrogate. Furthermore, it is not clear that violating Seth’s confidentiality would result in the social harms the authors forecast. In order to make this point, the authors would need to identify a case analogous to Seth’s, in which violating an incompetent person’s confidences is ill-advised because it might lead competent patients to mistrust or fear the health-care system.

In the previous section, we identified a variety of morally relevant factors in Seth’s case and suggested how they might affect one’s analysis. Determining the importance of the various factors in this case, however, requires the ethicist to obtain information concerning the following: the efficacy of antiviral treatment in HIV-positive persons, Seth and Maxwell’s sexual practices, the probability that Maxwell knows of Seth’s seropositivity, the degree to which Maxwell can reasonably be expected to know the risk of homosexual encounters, Seth’s previous comments regarding confidentiality, who is best situated to serve as Seth’s surrogate, and the degree to which violating an incompetent patient’s confidentiality will lead other patients to lose trust in physicians and thus avoid the health-care system. Some of this information might be obtained from Seth’s social worker. Other data, however, can be obtained only by reviewing the empirical literature. We admit that much of this information may be unobtainable. Knowing the limits of one’s knowledge, however, will allow an honest appraisal of how uncertainty regarding various factors affects one’s moral decision making. This is preferable to not attempting to ascertain the information at all.

CREATIVE SOLUTIONS

The failure to gather sufficient information often leads to an impoverished understanding of the ethical issues that a case raises. In Seth’s case, the authors present the case as though there were one question: Is it permissible/obligatory to violate Seth’s confidentiality to warn Maxwell? Asked this way, there appears to be only two resolutions to the case: either a physician protects Seth’s confidentiality by failing to warn Maxwell o the risk, or he violates Seth’s confidentiality by warning Maxwell. Upon collection of sufficient data, one might discover ways to resolve the case that would allow all relevant values to be promoted. In some cases, additional information may provide the ethicist with an “end run” around the presumed ethical problem. For instance, if the ethicist learns that Maxwell is already aware of Seth’s seropositivity, then the ethical quandary vanishes. There is strong pedagogical justification for the authors to provide us with sufficient information to conclude that the quandary could have been resolved by seeking additional information and to help us develop innovative solutions that might promote the competing values.

Even if more information does not allow one to avoid the ethical conflict, it may prove useful in determining how best to resolve the case. It is simplistic to view the outcome of ethical analysis as a hierarchical ranking of two competing values or principles. Intermediate solutions often exist, which allow one to respect both competing values. Even in those cases where it is justified to promote one value over another, one is nevertheless obligated to consider alternative courses of action that respect, as much as possible, the other value. The authors neglect an important step in ethical problem solving – attempting to develop creative solutions that, if they cannot perfectly respect all values, at least cause as little damage as possible. This approach, known in American law as “the least restrictive alternative,”6 recognizes that solutions can be more or less respectful of ethical principles. Thus, for example, one might decide that the risk to Maxwell is sufficiently high so that some violation of Seth’s confidentiality is permissible. A variety of options would still be open. (1) The psychiatrist could call Maxwell (or have the public health department do so) and inform him that he may have been exposed to the HIV virus and thus, he should be tested. (2) The psychiatrist could call Maxwell, identify himself as Seth’s physician, and attempt to ascertain what Maxwell knows about Seth’s serostatus and what the nature of their sexual relationship was. That evidence could then be used to determine whether further actions are in order. (3) The psychiatrist could call Maxwell and tell him that he is Seth’s physician, hat he knows of Maxwell and Seth’s sexual relationship, and that Seth is HIV positive. He could then urge Maxwell to be tested. A similar range of alternatives could be developed if one decides that respecting Seth’s confidentiality is the most important value.

PREVENTIVE ETHICS

A final question is simply why this problem arose. If we assume, as the authors do, that “choosing one solution [in an ethical dilemma] over another leaves behind an ethically significant value and regrettably may even produce harm,” we should attempt to prevent ethical dilemmas from occurring.7 However, typically, case discussions focus on how to “solve” the problem at hand without determining how and why the problem arose, and how it might be avoided in the future. As E. Haavi Morreim points out: “Our moral lives are comprised, not of terrible hypotheticals from which there are no escapes, but of complex situations whose constituent elements are often amenable to considerable alterations.”8 The psychiatrist in this case may not have been able to anticipate Seth’s disappearance, but perhaps he could have asked additional questions on his initial encounter to prevent the resulting ethical quandary. For instance, it would have been useful if the psychiatrist had gathered information about Seth’s values and desires prior to his decompensation. Furthermore, if the physician had asked Seth for permission to talk to his friends, whether others knew of his seropositivity, whether the doctor could release this information to Seth’s sexual partners. or to identify his moral surrogate, this additional information could have ameliorated the quandary that subsequently arose.

In the final analysis, we may well agree with Smith and Martin about how the psychiatrist should handle this case. In this article we have tried to criticize not the answer, but the process by which the answer was reached. We urge ethicists who are dealing with a challenging case to use the process of case comparison in their analysis, examining a variety of analogous cases; to seek sufficient information to be able to identify all the moral issues in a case and situate the case in its proper taxonomic family; to attempt to develop creative, “least-restrictive” alternatives to ethical dilemmas; and to determine if there are ways that the ethical problem can be prevented in the future. Close attention to these points is likely to improve ethical decision making in the clinical setting and ethical analyses of cases presented in the bioethics literature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank our friends and colleagues for their helpful comments on this paper: Lisa Parker, PhD; Joel Frader, MD; Peter Ubel, MD; and Shawn Wright. JD, MPH.

1. A.R. Jonsen, “Casuistry as Methodology in Clinical Ethics,” Theoretical Medicine 12 (1991): 295-307.

2. T.L Beauchamp and J.F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989).

3. 3c. Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 17 Cal. 3d 425. 551 P.2d 334 (1976}.

5. N. Whitman, Creative Medical Teaching (SaIt Lake City: University of Utah School of Medicine, 1990).

6. Lake v. Cameron. 364 F. 2d 657 (D.C. Cir. 1966).

7. L. Forrow R.M. Arnold and L.S. Parker, “Preventive Ethics: Expanding the Horizons of Clinical Ethics:· The Journal of Clinical Ethics (forthcoming).

8. E.H. Morreim, “Philosophy Lessons from the Clinical Sening.” Theoretical Medicine 7 (1986): 47-63.

TARASOFF: Discussion Questions

1. Traditionally, the Tarasoff case pits two goods or values against each other: confidentiality between therapist and patient vs. protection of an intended victim. Why is each a value?

2. Confidentiality is not only a value, but it has been called a duty which is incumbent on health care professionals to maintain secrecy about information gained in the course of interaction with a patient or client. Confidentiality derives from the more fundamental value of autonomy, the right each person has to be one’s own self-decider, one’s own intentional agent.

Protection of an intended victim likewise becomes a duty. To discharge that duty, the court argued, the therapist is obliged to warn the intended victim or others, to notify the police, or to take steps which are reasonably necessary to guard the intended victim.

Formulate an argument that supports the duty of confidentiality over the duty to warn an intended victim. Then formulate an argument which supports the duty to warn over the duty to protect confidentiality. (Being able to make good cases for each of the values shows the ambiguity involved here. Bring into your arguments the issue of the foreseeability of violence (is violence clearly foreseeable, probably foreseeable or unforseeable?) and the element of control over the patient by the therapist.)

3. One can easily use the Tarasoff decision to show the two principal ways of argument, consequentialist and non-consequentialist. Formulate an argument from a utilitarian (consequentialist) perspective, i.e., emphasize risk over benefit in arguing for safety and again, in arguing for confidentiality.

Next, consider confidentiality and the right to be protected as goods in themselves, regardless of consequences. Show how each value is tied to the meaning of being human and indicate how such a value can be argued for without consideration of consequences.

4. Notice how the arguments being proposed by the committee deny the absolute nature of either value. Rather, the committee is attempting to justify an action that is indicated in favor of one value over another, while acknowledging that both values are human goods. How would one attempt to argue when faced with the position that confidentiality or protection were absolute values?

Further Readings

Beauchamp, Tom and LeRoy Walters (eds.) 1994. “The Management of Medical Information” in Contemporary Issues in Bioethics. Fourth Edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth:123-186.

Kleinman, Irwin. 1993. “Confidentiality and the Duty to Warn.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 149: 1783-1785.

Perlin, Michael L. 1992. “Tarasoff and the Dilemma of the Dangerous Patient: New Directions for the 1990’s.” Law and Psychology Review 16: 29-63.

- Open access

- Published: 14 March 2022

Health professionals' knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality and associated factors in a resource-limited setting: a cross-sectional study

- Masresha Derese Tegegne 1 ,

- Mequannent Sharew Melaku 1 ,

- Aynadis Worku Shimie 2 ,

- Degefaw Denekew Hunegnaw 3 ,

- Meseret Gashaw Legese 4 ,

- Tewabe Ambaye Ejigu 5 ,

- Nebyu Demeke Mengestie 1 ,

- Wondewossen Zemene 1 ,

- Tirualem Zeleke 1 &

- Ashenafi Fentahun Chanie 1

BMC Medical Ethics volume 23 , Article number: 26 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

34k Accesses

15 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Respecting patients’ confidentiality is an ethical and legal responsibility for health professionals and the cornerstone of care excellence. This study aims to assess health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and associated factors towards patients’ confidentiality in a resource-limited setting.

Institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted among 423 health professionals. Stratified sampling methods were used to select the participants, and a structured self-administer questionnaire was used for data collection. The data was entered using Epi-data version 4.6 and analyzed using SPSS, version 25. Bi-variable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were used to measure the association between the dependent and independent variables. Odds ratio with 95% confidence intervals and P value was calculated to determine the strength of association and to evaluate statistical significance.

Out of 410 participants, about 59.8% with [95% CI (54.8–68.8%)] and 49.5% with [95% CI (44.5–54.5%)] had good knowledge and favorable attitude towards patents confidentiality respectively. Being male (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI [1.03–2.59]), taking training on medical ethics (AOR = 1.73, 95% CI = [1.11–2.70]), facing ethical dilemmas (AOR = 3.07, 95% CI [1.07–8.79]) were significantly associated factors for health professional knowledge towards patients’ confidentiality. Likewise, taking training on medical ethics (AOR = 2.30, 95% CI [1.42–3.72]), having direct contact with the patients (AOR = 3.06, 95% CI [1.12–8.34]), visiting more patient (AOR = 4.38, 95% CI [2.46–7.80]), and facing ethical dilemma (AOR = 3.56, 95% CI [1.23–10.26]) were significant factors associated with attitude of health professionals towards patient confidentiality.

The findings of this study revealed that health professionals have a limited attitude towards patient confidentiality but have relatively good knowledge. Providing a continuing medical ethics training package for health workers before joining the hospital and in between the working time could be recommended to enhance health professionals’ knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Confidentiality refers to the restriction of access to personal information from unauthorized persons and processes at authorized times and in an authorized manner [ 1 , 2 ]. When we say patients have the right to confidentiality, it refers to keeping privileged communication secret and cannot be disclosed without the patient’s authorization [ 3 , 4 ].

Health professionals have a legal obligation to handle patients' information privately and securely [ 5 ]. As a result, patients and professionals develop trust and a positive relationship. If such highly sensitive data is improperly disclosed, it could threaten patients' safety [ 6 ]. Hence confidentiality needs to be respected to protect patients’ well-being and maintain society’s trust in the physician–patient relationship. The issue of confidentiality has been recognized as a global concern. As a result, several internationally agreed on principles and guidelines for maintaining the sanctity of patients’ private lives during treatment. This law, known as Data Protection Act, was enacted in 1998 and was last revised in 2018 [ 7 , 8 ]. The Data Protection Act was created to provide protection and set guidelines for handling personal data [ 7 ]. There is no comprehensive data protection law in Ethiopia that covers health data protection [ 9 ]. Ethiopia's only confidentiality-oriented policy is the healthcare administration law, which requires health practitioners to maintain confidentiality. This law mandates health providers to keep patients' health information confidential [ 10 ]. Furthermore, only a few research have looked into health professionals' awareness of ethical rules and data security and sharing laws in Ethiopia [ 9 ].

Confidentiality is the basis of the legal elements of health records and an ethical cornerstone of excellent care [ 11 ]. More importantly, the quality of information shared with healthcare experts is determined by their capacity to keep it private. Otherwise, the patient may withhold important information, lowering the quality of care offered.

Although information sharing is essential in an interdisciplinary health team, each professional should limit information disclosure to an unauthorized health professional to plan and carry out procedures in the patient's best interests [ 12 ]. The exchange of patient medical records and data with an unauthorized person continues to be a common occurrence in a variety of clinical settings [ 5 ]. Breaches of confidentiality in clinical practice due to negligence, indiscretion, or sometimes even maliciously jeopardize a duty inherent in the physician–patient relationship [ 8 ]. Breaches of confidentiality and sharing data with unauthorized parties may have the potential to harm the patients’ health [ 13 ]. Health care quality declines due to a loss of confidence in the professional-patient relationship [ 14 ]. Patients become hesitant to seek care and attend follow-up appointments due to their mistrust of health providers [ 7 , 8 ].

Until recently, the standard curricula of Ethiopia's recent medical schools did not include a medical ethics course. Nevertheless, following proposals from the Ethiopian Medical Association and curriculum review committees, the medical ethics course was first established at Addis Ababa University's Faculty of Medicine in 2004 [ 15 ]. Despite the existence of a medical ethics course, patients' concern about maintaining their confidentiality has grown, and reports of unethical behavior by health professionals on patient confidentiality are familiar [ 15 ].

There are so many problems regarding patient medical record confidentiality and data sharing [ 16 ]. The loss of patient medical records due to handling by unauthorized staff without consent and transporting to another department is a big issue in Ethiopia. That can affect patients’ quality of care by consuming time, harming patient satisfaction, causing improper diagnosis, and making it difficult to get the previous history.

The significance of this research is that it addresses the rapidly growing trend of patient data sharing and confidentiality among health practitioners in developing countries taking Ethiopia as an example. There is limited evidence regarding health professional knowledge and attitude related to patients’ confidentiality in resources limited settings. Therefore, this study will fill evidence gaps on health professional knowledge, attitude, and associated factors related to patient confidentiality in Ethiopia. This study will provide policymakers with up-to-date information on health professionals' knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality. Aside from that, the outcomes of this study may aid legislators in developing plans to improve health professionals' knowledge and attitude toward patient confidentiality.

Study design and setting

An Institutional based cross-sectional study was conducted among health professionals from August–September 2021. Gondar is a historical town situated in the northwestern part of Ethiopia, 772 km far from the capital Addis Ababa and 168 km from Bahir Dar [ 17 ]. The University of Gondar specialized hospital is one of the largest teaching hospitals in the Amhara region providing tertiary level care for more than seven million people in the northwest part of the country coming from Amhara, Tigray, and Benishangul Gumuz regions [ 18 ]. It has 960 health professionals distributed over 30 services units responsible for delivering healthcare services to an average of 800 patients per day.

Study subjects and eligibility criteria

All healthcare professionals working in the University of Gondar specialized hospital and those available during the study period were the sources and study population. The study excluded health professionals with less than six months of experience, those who had not been found in the hospital for various reasons, and those on yearly leave during the data collection period.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

The sample size was calculated using the single population proportion formula, n = Z(α/2) 2 pq/d 2 [ 19 ]. We assumed: n = the required sample size, Z = the value of standard normal distribution corresponding to α/2, 1.96, p = proportion of health professionals who had good knowledge and attitude towards confidentiality, q = proportion of health professionals who had unfavorable knowledge and attitude towards confidentiality, and d = precision assumed as 0.05. To our knowledge, no study has been conducted in Ethiopia to determine the knowledge and attitude of health professionals towards patient confidentiality. Therefore, we assumed p (proportion of health professionals who had good knowledge and attitude towards confidentiality) to be 0.5. Hence, the required sample size was calculated to be 384. After adding a 10% non-response rate, 423 health care professionals were enrolled in the study.

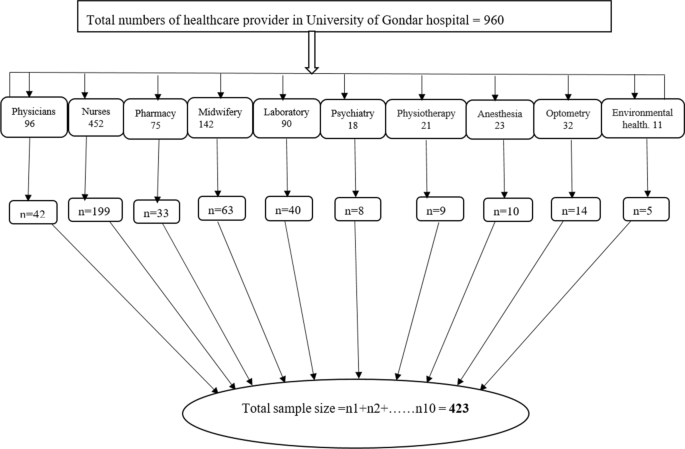

Stratified with a simple random sampling method was used to select the 423 participants. Firstly, the sample was stratified based on their department. Then the selection was proportionally allocated in each stratum depending on the numbers of healthcare providers in each stratum or department to assess their knowledge, attitude, and associated factors related to patients' confidentiality. After allocating samples in each stratum proportionally, a computer-generated simple random sampling technique was employed to select the study subjects in each department (Fig. 1 ).

Sampling procedure and sample allocation in University of Gondar hospital

Study variables

The primary outcome variable of this study was knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality. The questionnaires used in this study were developed based on a review of related literature [ 20 , 21 ]. Socio-demographic and work-related characteristics were used as independent variables in this study.

Operational definitions

Knowledge about patients' confidentiality was assessed using seven items with “yes” and “no” responses. Each correct answer was equal to one point, while each incorrect answer was equal to zero points, with a height possible score of 7 for the knowledge part. A mean of 7 questions regarding Knowledge towards patient confidentiality was calculated. And those above the mean score were categorized as ‘good’ knowledge, and those below were categorized as ‘poor’ knowledge [ 20 ].

Attitudes toward patient confidentiality were assessed by using 14 questions with a 5 point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (score 1) to ‘strongly agree’ (score 5) [ 20 ]. The final score in the attitude section ranges from 14 to 70. A mean of the 14 questions of attitude towards patient’s confidentiality was calculated. Those above the mean value were categorized as ‘favorable’ attitude, and those below the mean value were categorized as ‘unfavorable’ attitude [ 20 ].

Data collection tool and quality control

A self-administered, organized, and pre-tested questionnaire was created in English. The data collection process included two supervisors and ten data collectors. One-day training was given to the data collectors to eliminate ambiguities. A pre-test was conducted outside of the study area, in Gondar town health centers, with 10% of the study population. The validity and reliability of the data collection instrument were assessed using the pre-test results. The Cronbach alpha value for the attitude questions was 0.82, whereas the Cronbach alpha value for the knowledge questions was 0.76. These figures show that the questionnaire is highly reliable.

Data processing and analysis

The data entry was performed using Epi Data version 4.6 software packages and analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25. Descriptive statistics were computed to describe the socio-demographic variables and health professionals’ knowledge and attitudes about patient confidentiality and data sharing. Bi-variable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were done to measure the association between the dependent and independent variables. In the bi-variable regression analysis, variables with a p value of less than 0.2 were included in the multivariable regression analysis to assess their adjusted impacts on the dependent variables. Odds ratio with 95% confidence level and P value were calculated to ascertain the strength of association and to decide statistical significance. For all significantly associated variables, the cut-off value was p < 0.05. Before conducting the logistic regression model, assumptions of multi-collinearity were checked. The result revealed all the variance inflation factor (VIF) values less than three, which confirmed the absence of multi-collinearity.

Description of participant’s socio-demographic and work-related characteristics

Of 423 participants, 410 responded to a questionnaire with a 96.9% response rate. The mean age of the participants was 28.12(SD ± 5.16) years which ranges from 21 to 50 years. The majority 271(66.1%) of the study participants were male and most of them 334 (81.5%) were orthodox religious followers. In terms of the educational level of the health professional, more than half 228 (55.6%) of participants have a BSc degree (Table 1 ). Of the total respondents, above three fourth 79.8% health professionals had below five years of work experience. A majority 47.8% of respondents were nurse professionals. Almost all 95.4% health professionals had direct contact with the patients and around 39% had visits above 40 patients per day. The results showed that about 5.9% of health professionals faced more than two ethical dilemmas daily while treating patients. In addition, 44.1% of the participants were taking training on medical ethics (Table 1 ).

Health professionals’ knowledge about patients’ confidentiality

Of the total participants, 59.8% with [95% CI (54.9–64.5%)] had good knowledge about confidentiality with a mean score of 3.91(SD ± 1.39) (out of a maximum of 7 points) (Fig. 2 ). From the knowledge questionnaire, most of the respondents 358(87.3%) were said ‘access to medical records should be governed by law’ and 183(44.6%) argued that non-medical information is also confidential. Furthermore, 291(71%) health professionals were aware that third-party insurance companies did not access patient examination results (such as insurance companies) without patient consent. However, only 115(28.0%) of participants knew that policies were not allowed to access medical records freely (Table 2 ).

Health professional knowledge and attitude related to patients’ confidentiality

Health professionals attitude towards patients’ confidentiality

Of the total participants, 49.5% with [95% CI (44.6–54.3%)] had a favorable attitude towards confidentiality with a mean score of 42.8(SD ± 8.90) (out of a maximum of 70 points) (Fig. 2 ). Table 3 illustrates that about 126(30.7%) of participants agreed that confidentiality affects the patient in any way, and 299(72.9%) believed they don’t allow non-medical personnel to enter the examination room while they are discussing with patients. Of all respondents, 220(53.7%) and 162(39.5%) participants use lock systems and computers to store patient information.

Factors associated with health professionals’ knowledge about patients’ confidentiality

Bi-variable and multivariable binary logistic regression analyses were done to measure the association between Health professionals’ knowledge towards patients’ confidentiality and independent variables. In bi-variable regression, Sex of participants, Age of the respondents, Work experience, Training on medical ethics, Numbers of the patient served, Direct contact with the patients, Numbers of ethical dilemmas faced, Income of participants were the candidates’ variables for health professionals’ knowledge towards confidentiality for the multivariable regression analysis ( P < 0.2). With the multivariable regression model sex of respondents, training on medical ethics, number of ethical dilemmas faced were significantly associated factors for health professional knowledge towards patients’ confidentiality (Table 4 ). This means that being male was (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI [1.03–2.59]) times more likely to have good knowledge towards patient confidentiality as compared to females after controlling for other factors. Health professionals taking training on medical ethics were (AOR = 1.73, 95% CI = [1.11–2.70]) times more likely to have a good knowledge towards patients’ confidentiality as compared to their counterparts. Similarly, health professionals who faced more ethical dilemmas were (AOR = 3.07, 95% CI [1.07–8.79]) times more likely to have good knowledge than those who faced fewer ethical dilemmas.

Factors associated with health professionals’ attitude towards patients’ confidentiality

In both bi-variable and multivariable analysis training on medical ethics, direct contact with the patients, Numbers of patient visits, and numbers of ethical dilemmas faced were significant variables to the attitude of health professionals towards patient confidentiality (Table 5 ).

Health professionals taking on medical ethics were (AOR = 2.30, 95% CI [1.42–3.72]) times more likely to have a favorable attitude towards patient confidentiality when compared to those who didn’t take any pieces of training on medical ethics. Health professionals who had direct contact with the patients were (AOR = 3.06, 95% CI [1.12–8.34]) times more likely to have a favorable attitude towards patient confidentiality than those who didn’t have direct contact with the patients. Health professionals who visited more patients daily (more than 40 and 30–40) were approximately (AOR = 4.38, 95% CI [2.46–7.80]) and (AOR = 1.96, 95% CI [1.12–3.43]) times more likely to have a favorable attitude towards patients’ confidentiality when compared to those who visited less than 30 patients daily. Additionally, respondents who faced more ethical dilemmas were (AOR = 3.56, 95% CI [1.23–10.26]) times more likely to have a favorable attitude towards patients’ confidentiality than those who faced fewer ethical dilemmas.

This study examines health professionals’ knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality and associated factors in Northwest Ethiopia.

This study revealed that around 59.8% of respondents had good knowledge related to patient confidentiality. The finding is in line with two studies conducted in Iran 56.6% [ 22 ], 63% [ 23 ]. However, the results of this study demonstrated that health professionals’ good knowledge towards patient confidentiality was lower than studies conducted in Spain 68% [ 24 ] and Tehran university medical school 65% [ 25 ]. The difference could be that health professionals working in high-resource countries are more informed about patients' privacy in their daily lives and recognize the relative benefit of patient confidentiality [ 26 ]. The other reasons for the disparity could be explained by the fact that approximately 75% of participants had less than 5 years of professional experience in the current study, and they were also considerably younger than in the Spanish study [ 24 ]. Furthermore, the participants in Spain were all physicians, who are supposed to have better clinical data management and specific training [ 24 ].

In this study, 49.5% of participants had a favorable attitude towards patient confidentiality. This finding is supported by the study conducted in northern Jordan 52.4% [ 20 ]. However, this finding is lower than the study conducted in Turkey (64.4%) physicians strongly agreed to protect patient confidentiality [ 27 ]. The possible reason could be that difference awareness among health professionals in different countries results in a good level of attitude.

The study also found factors associated with health professionals’ knowledge and attitude regarding patient confidentiality. The sex of respondents, training on medical ethics, and the number of ethical dilemmas faced was all significantly associated factors of health professional knowledge towards patients’ confidentiality. Likewise, training on medical ethics, direct contact with the patients, Numbers of patient visits, and numbers of ethical dilemmas faced were significant variables to the attitude of health professionals towards patient confidentiality.

Among the factors associated with knowledge, being males were more likely to have good knowledge towards patient confidentiality than females. This finding is consistent with study findings from Jordan [ 20 , 21 ], Spain [ 24 ], and the United States [ 28 ]. This might be due to males were more access to information and technology and there is high information sharing between them [ 21 ]. Furthermore, the number of ethical dilemmas experienced and training on medical ethics were revealed to be predictive variables for both knowledge and attitude. Health professionals taking training on medical ethics were more likely to have a good knowledge and attitude related to patients’ confidentiality than those who had not taken the training. The greatest strategy to ensure adherence to confidentiality laws was to provide training on medical ethics, where health organizations would routinely update all health professionals on guidelines and strategies to prevent sensitive information disclosure [ 21 , 29 , 30 ]. Furthermore, the legislature's role is critical, not just in terms of legal norms to safeguard patient confidentiality, but also in terms of punishments when inappropriate behavior occurs [ 31 ]. And this finding is supported by a study conducted in Barbados [ 32 ], Vietnam [ 33 ]. Besides this, this study also found that health professionals who faced more ethical dilemmas were more likely to have good knowledge and attitude as compared to those who faced a less ethical dilemma. According to Hariharan et al. suggestions, health professionals may not report such problems to their seniors and try to solve them [ 32 ]. This may be the possible reasons for facing more ethical dilemma and trying to solve by themselves to have positive knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality.

In addition, direct contact with the patients and the number of patient visits were associated with a favorable attitude towards patient confidentiality. Respondents who have direct contact with the patients were more aware of confidentiality. This could be because the health of practitioners that deal with patients regularly are more familiar with confidentiality rules and strategies[ 22 ]. Besides this, health professionals who visit more patients per day were more likely to have a favorable attitude related to patient confidentiality. This might be because when health professionals serve more patients per day, they get a lot of challenges which helps to change their attitude to maintain the patient's information confidentially.

The findings of this study revealed that health professionals have a limited attitude towards patient confidentiality but have relatively good knowledge. The sex of respondents, training on medical ethics, and many ethical dilemmas faced were significantly associated factors of health professional knowledge towards patients’ confidentiality. Likewise, training on medical ethics, direct contact with the patients, Numbers of patient visits, and numbers of ethical dilemmas faced were significant variables to the attitude of health professionals towards patient confidentiality. Providing a continuing medical ethics training package for health workers before joining the hospital and in between the working time could be recommended to improve health professionals' knowledge and attitude towards patient confidentiality.

Strength and limitations

The findings from this study provide valuable information on health professionals' knowledge and attitude related to patients' confidentiality in resources limited countries. There are some limitations to this study. First, this study was an institution-based cross-sectional survey; only health professionals who came during the data collection period were interviewed.

Availability of data and materials

All the data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and supplementary information [SPSS Data Knowledge and SPSS Data Attitude].

Abbreviations

Adjusted odds ratio

Confidence interval

Epidemiological information

Information communication technology

Statistical package for social science

de Sousa Costa R, de Castro Ruivo I, editors. Preliminary remarks and practical insights on how the whistleblower protection directive adopts the GDPR principles. Annual Privacy Forum; 2020. Springer.

Štarchoň P, Pikulík T. GDPR principles in data protection encourage pseudonymization through most popular and full-personalized devices-mobile phones. Procedia Comput Sci. 2019;151:303–12.

Article Google Scholar

Drogin EY. Confidentiality, privilege, and privacy. 2019.

Romeo C. Enciclopedia de Bioderecho y Bioética. Cuad Med Forense. 2012;18(3–4):144–5.

Google Scholar

Beltran-Aroca CM, Girela-Lopez E, Collazo-Chao E, Montero-Pérez-Barquero M, Muñoz-Villanueva MC. Confidentiality breaches in clinical practice: what happens in hospitals? BMC Med Ethics. 2016;17(1):1–12.

Parsa M. Privacy and confidentiality in medical field and its various aspects. J Med Ethics Hist. 2009;4:1–14.

Spencer A, Patel S. Applying the data protection act 2018 and general data protection regulation principles in healthcare settings. Nurs Manag. 2019;26(1):34.

Act DP. Data protection act. London Station Off. 2018;5.