- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Quantitative Methods

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Quantitative methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques . Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Muijs, Daniel. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Need Help Locating Statistics?

Resources for locating data and statistics can be found here:

Statistics & Data Research Guide

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Your goal in conducting quantitative research study is to determine the relationship between one thing [an independent variable] and another [a dependent or outcome variable] within a population. Quantitative research designs are either descriptive [subjects usually measured once] or experimental [subjects measured before and after a treatment]. A descriptive study establishes only associations between variables; an experimental study establishes causality.

Quantitative research deals in numbers, logic, and an objective stance. Quantitative research focuses on numeric and unchanging data and detailed, convergent reasoning rather than divergent reasoning [i.e., the generation of a variety of ideas about a research problem in a spontaneous, free-flowing manner].

Its main characteristics are :

- The data is usually gathered using structured research instruments.

- The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population.

- The research study can usually be replicated or repeated, given its high reliability.

- Researcher has a clearly defined research question to which objective answers are sought.

- All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected.

- Data are in the form of numbers and statistics, often arranged in tables, charts, figures, or other non-textual forms.

- Project can be used to generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or investigate causal relationships.

- Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or computer software, to collect numerical data.

The overarching aim of a quantitative research study is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed.

Things to keep in mind when reporting the results of a study using quantitative methods :

- Explain the data collected and their statistical treatment as well as all relevant results in relation to the research problem you are investigating. Interpretation of results is not appropriate in this section.

- Report unanticipated events that occurred during your data collection. Explain how the actual analysis differs from the planned analysis. Explain your handling of missing data and why any missing data does not undermine the validity of your analysis.

- Explain the techniques you used to "clean" your data set.

- Choose a minimally sufficient statistical procedure ; provide a rationale for its use and a reference for it. Specify any computer programs used.

- Describe the assumptions for each procedure and the steps you took to ensure that they were not violated.

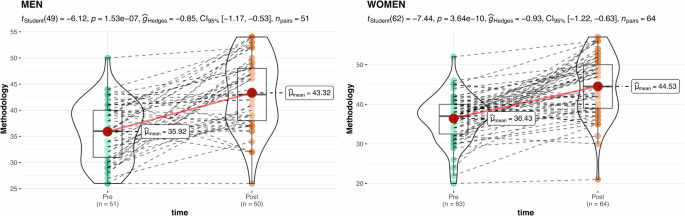

- When using inferential statistics , provide the descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and sample sizes for each variable as well as the value of the test statistic, its direction, the degrees of freedom, and the significance level [report the actual p value].

- Avoid inferring causality , particularly in nonrandomized designs or without further experimentation.

- Use tables to provide exact values ; use figures to convey global effects. Keep figures small in size; include graphic representations of confidence intervals whenever possible.

- Always tell the reader what to look for in tables and figures .

NOTE: When using pre-existing statistical data gathered and made available by anyone other than yourself [e.g., government agency], you still must report on the methods that were used to gather the data and describe any missing data that exists and, if there is any, provide a clear explanation why the missing data does not undermine the validity of your final analysis.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Quantitative Research Methods. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Basic Research Design for Quantitative Studies

Before designing a quantitative research study, you must decide whether it will be descriptive or experimental because this will dictate how you gather, analyze, and interpret the results. A descriptive study is governed by the following rules: subjects are generally measured once; the intention is to only establish associations between variables; and, the study may include a sample population of hundreds or thousands of subjects to ensure that a valid estimate of a generalized relationship between variables has been obtained. An experimental design includes subjects measured before and after a particular treatment, the sample population may be very small and purposefully chosen, and it is intended to establish causality between variables. Introduction The introduction to a quantitative study is usually written in the present tense and from the third person point of view. It covers the following information:

- Identifies the research problem -- as with any academic study, you must state clearly and concisely the research problem being investigated.

- Reviews the literature -- review scholarship on the topic, synthesizing key themes and, if necessary, noting studies that have used similar methods of inquiry and analysis. Note where key gaps exist and how your study helps to fill these gaps or clarifies existing knowledge.

- Describes the theoretical framework -- provide an outline of the theory or hypothesis underpinning your study. If necessary, define unfamiliar or complex terms, concepts, or ideas and provide the appropriate background information to place the research problem in proper context [e.g., historical, cultural, economic, etc.].

Methodology The methods section of a quantitative study should describe how each objective of your study will be achieved. Be sure to provide enough detail to enable the reader can make an informed assessment of the methods being used to obtain results associated with the research problem. The methods section should be presented in the past tense.

- Study population and sampling -- where did the data come from; how robust is it; note where gaps exist or what was excluded. Note the procedures used for their selection;

- Data collection – describe the tools and methods used to collect information and identify the variables being measured; describe the methods used to obtain the data; and, note if the data was pre-existing [i.e., government data] or you gathered it yourself. If you gathered it yourself, describe what type of instrument you used and why. Note that no data set is perfect--describe any limitations in methods of gathering data.

- Data analysis -- describe the procedures for processing and analyzing the data. If appropriate, describe the specific instruments of analysis used to study each research objective, including mathematical techniques and the type of computer software used to manipulate the data.

Results The finding of your study should be written objectively and in a succinct and precise format. In quantitative studies, it is common to use graphs, tables, charts, and other non-textual elements to help the reader understand the data. Make sure that non-textual elements do not stand in isolation from the text but are being used to supplement the overall description of the results and to help clarify key points being made. Further information about how to effectively present data using charts and graphs can be found here .

- Statistical analysis -- how did you analyze the data? What were the key findings from the data? The findings should be present in a logical, sequential order. Describe but do not interpret these trends or negative results; save that for the discussion section. The results should be presented in the past tense.

Discussion Discussions should be analytic, logical, and comprehensive. The discussion should meld together your findings in relation to those identified in the literature review, and placed within the context of the theoretical framework underpinning the study. The discussion should be presented in the present tense.

- Interpretation of results -- reiterate the research problem being investigated and compare and contrast the findings with the research questions underlying the study. Did they affirm predicted outcomes or did the data refute it?

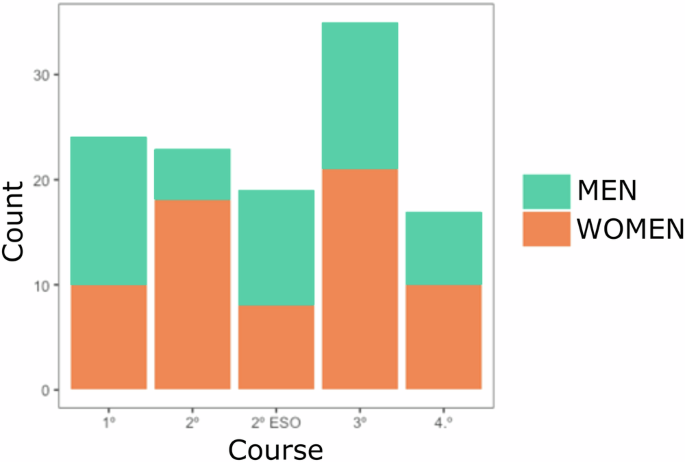

- Description of trends, comparison of groups, or relationships among variables -- describe any trends that emerged from your analysis and explain all unanticipated and statistical insignificant findings.

- Discussion of implications – what is the meaning of your results? Highlight key findings based on the overall results and note findings that you believe are important. How have the results helped fill gaps in understanding the research problem?

- Limitations -- describe any limitations or unavoidable bias in your study and, if necessary, note why these limitations did not inhibit effective interpretation of the results.

Conclusion End your study by to summarizing the topic and provide a final comment and assessment of the study.

- Summary of findings – synthesize the answers to your research questions. Do not report any statistical data here; just provide a narrative summary of the key findings and describe what was learned that you did not know before conducting the study.

- Recommendations – if appropriate to the aim of the assignment, tie key findings with policy recommendations or actions to be taken in practice.

- Future research – note the need for future research linked to your study’s limitations or to any remaining gaps in the literature that were not addressed in your study.

Black, Thomas R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics . London: Sage, 1999; Gay,L. R. and Peter Airasain. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications . 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merril Prentice Hall, 2003; Hector, Anestine. An Overview of Quantitative Research in Composition and TESOL . Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Hopkins, Will G. “Quantitative Research Design.” Sportscience 4, 1 (2000); "A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper." Department of Biology. Bates College; Nenty, H. Johnson. "Writing a Quantitative Research Thesis." International Journal of Educational Science 1 (2009): 19-32; Ouyang, Ronghua (John). Basic Inquiry of Quantitative Research . Kennesaw State University.

Strengths of Using Quantitative Methods

Quantitative researchers try to recognize and isolate specific variables contained within the study framework, seek correlation, relationships and causality, and attempt to control the environment in which the data is collected to avoid the risk of variables, other than the one being studied, accounting for the relationships identified.

Among the specific strengths of using quantitative methods to study social science research problems:

- Allows for a broader study, involving a greater number of subjects, and enhancing the generalization of the results;

- Allows for greater objectivity and accuracy of results. Generally, quantitative methods are designed to provide summaries of data that support generalizations about the phenomenon under study. In order to accomplish this, quantitative research usually involves few variables and many cases, and employs prescribed procedures to ensure validity and reliability;

- Applying well established standards means that the research can be replicated, and then analyzed and compared with similar studies;

- You can summarize vast sources of information and make comparisons across categories and over time; and,

- Personal bias can be avoided by keeping a 'distance' from participating subjects and using accepted computational techniques .

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Limitations of Using Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods presume to have an objective approach to studying research problems, where data is controlled and measured, to address the accumulation of facts, and to determine the causes of behavior. As a consequence, the results of quantitative research may be statistically significant but are often humanly insignificant.

Some specific limitations associated with using quantitative methods to study research problems in the social sciences include:

- Quantitative data is more efficient and able to test hypotheses, but may miss contextual detail;

- Uses a static and rigid approach and so employs an inflexible process of discovery;

- The development of standard questions by researchers can lead to "structural bias" and false representation, where the data actually reflects the view of the researcher instead of the participating subject;

- Results provide less detail on behavior, attitudes, and motivation;

- Researcher may collect a much narrower and sometimes superficial dataset;

- Results are limited as they provide numerical descriptions rather than detailed narrative and generally provide less elaborate accounts of human perception;

- The research is often carried out in an unnatural, artificial environment so that a level of control can be applied to the exercise. This level of control might not normally be in place in the real world thus yielding "laboratory results" as opposed to "real world results"; and,

- Preset answers will not necessarily reflect how people really feel about a subject and, in some cases, might just be the closest match to the preconceived hypothesis.

Research Tip

Finding Examples of How to Apply Different Types of Research Methods

SAGE publications is a major publisher of studies about how to design and conduct research in the social and behavioral sciences. Their SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases database includes contents from books, articles, encyclopedias, handbooks, and videos covering social science research design and methods including the complete Little Green Book Series of Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences and the Little Blue Book Series of Qualitative Research techniques. The database also includes case studies outlining the research methods used in real research projects. This is an excellent source for finding definitions of key terms and descriptions of research design and practice, techniques of data gathering, analysis, and reporting, and information about theories of research [e.g., grounded theory]. The database covers both qualitative and quantitative research methods as well as mixed methods approaches to conducting research.

SAGE Research Methods Online and Cases

- << Previous: Qualitative Methods

- Next: Insiderness >>

- Last Updated: Aug 13, 2024 12:57 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

A Quick Guide to Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences

(12 reviews)

Christine Davies, Carmarthen, Wales

Copyright Year: 2020

Last Update: 2021

Publisher: University of Wales Trinity Saint David

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Jennifer Taylor, Assistant Professor, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi on 4/18/24

This resource is a quick guide to quantitative research in the social sciences and not a comprehensive resource. It provides a VERY general overview of quantitative research but offers a good starting place for students new to research. It... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This resource is a quick guide to quantitative research in the social sciences and not a comprehensive resource. It provides a VERY general overview of quantitative research but offers a good starting place for students new to research. It offers links and references to additional resources that are more comprehensive in nature.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

The content is relatively accurate. The measurement scale section is very sparse. Not all types of research designs or statistical methods are included, but it is a guide, so details are meant to be limited.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

The examples were interesting and appropriate. The content is up to date and will be useful for several years.

Clarity rating: 5

The text was clearly written. Tables and figures are not referenced in the text, which would have been nice.

Consistency rating: 5

The framework is consistent across chapters with terminology clearly highlighted and defined.

Modularity rating: 5

The chapters are subdivided into section that can be divided and assigned as reading in a course. Most chapters are brief and concise, unless elaboration is necessary, such as with the data analysis chapter. Again, this is a guide and not a comprehensive text, so sections are shorter and don't always include every subtopic that may be considered.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The guide is well organized. I appreciate that the topics are presented in a logical and clear manner. The topics are provided in an order consistent with traditional research methods.

Interface rating: 5

The interface was easy to use and navigate. The images were clear and easy to read.

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The materials are not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way.

I teach a Marketing Research course to undergraduates. I would consider using some of the chapters or topics included, especially the overview of the research designs and the analysis of data section.

Reviewed by Tiffany Kindratt, Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Arlington on 3/9/24

The text provides a brief overview of quantitative research topics that is geared towards research in the fields of education, sociology, business, and nursing. The author acknowledges that the textbook is not a comprehensive resource but offers... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 3 see less

The text provides a brief overview of quantitative research topics that is geared towards research in the fields of education, sociology, business, and nursing. The author acknowledges that the textbook is not a comprehensive resource but offers references to other resources that can be used to deepen the knowledge. The text does not include a glossary or index. The references in the figures for each chapter are not included in the reference section. It would be helpful to include those.

Overall, the text is accurate. For example, Figure 1 on page 6 provides a clear overview of the research process. It includes general definitions of primary and secondary research. It would be helpful to include more details to explain some of the examples before they are presented. For instance, the example on page 5 was unclear how it pertains to the literature review section.

In general, the text is relevant and up-to-date. The text includes many inferences of moving from qualitative to quantitative analysis. This was surprising to me as a quantitative researcher. The author mentions that moving from a qualitative to quantitative approach should only be done when needed. As a predominantly quantitative researcher, I would not advice those interested in transitioning to using a qualitative approach that qualitative research would enhance their research—not something that should only be done if you have to.

Clarity rating: 4

The text is written in a clear manner. It would be helpful to the reader if there was a description of the tables and figures in the text before they are presented.

Consistency rating: 4

The framework for each chapter and terminology used are consistent.

Modularity rating: 4

The text is clearly divided into sections within each chapter. Overall, the chapters are a similar brief length except for the chapter on data analysis, which is much more comprehensive than others.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The topics in the text are presented in a clear and logical order. The order of the text follows the conventional research methodology in social sciences.

I did not encounter any interface issues when reviewing this text. All links worked and there were no distortions of the images or charts that may confuse the reader.

Grammatical Errors rating: 3

There are some grammatical/typographical errors throughout. Of note, for Section 5 in the table of contents. “The” should be capitalized to start the title. In the title for Table 3, the “t” in typical should be capitalized.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The examples are culturally relevant. The text is geared towards learners in the UK, but examples are relevant for use in other countries (i.e., United States). I did not see any examples that may be considered culturally insensitive or offensive in any way.

I teach a course on research methods in a Bachelor of Science in Public Health program. I would consider using some of the text, particularly in the analysis chapter to supplement the current textbook in the future.

Reviewed by Finn Bell, Assistant Professor, University of Michigan, Dearborn on 1/3/24

For it being a quick guide and only 26 pages, it is very comprehensive, but it does not include an index or glossary. read more

For it being a quick guide and only 26 pages, it is very comprehensive, but it does not include an index or glossary.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

As far as I can tell, the text is accurate, error-free and unbiased.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

This text is up-to-date, and given the content, unlikely to become obsolete any time soon.

The text is very clear and accessible.

The text is internally consistent.

Given how short the text is, it seems unnecessary to divide it into smaller readings, nonetheless, it is clearly labelled such that an instructor could do so.

The text is well-organized and brings readers through basic quantitative methods in a logical, clear fashion.

Easy to navigate. Only one table that is split between pages, but not in a way that is confusing.

There were no noticeable grammatical errors.

The examples in this book don't give enough information to rate this effectively.

This text is truly a very quick guide at only 26 double-spaced pages. Nonetheless, Davies packs a lot of information on the basics of quantitative research methods into this text, in an engaging way with many examples of the concepts presented. This guide is more of a brief how-to that takes readers as far as how to select statistical tests. While it would be impossible to fully learn quantitative research from such a short text, of course, this resource provides a great introduction, overview, and refresher for program evaluation courses.

Reviewed by Shari Fedorowicz, Adjunct Professor, Bridgewater State University on 12/16/22

The text is indeed a quick guide for utilizing quantitative research. Appropriate and effective examples and diagrams were used throughout the text. The author clearly differentiates between use of quantitative and qualitative research providing... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The text is indeed a quick guide for utilizing quantitative research. Appropriate and effective examples and diagrams were used throughout the text. The author clearly differentiates between use of quantitative and qualitative research providing the reader with the ability to distinguish two terms that frequently get confused. In addition, links and outside resources are provided to deepen the understanding as an option for the reader. The use of these links, coupled with diagrams and examples make this text comprehensive.

The content is mostly accurate. Given that it is a quick guide, the author chose a good selection of which types of research designs to include. However, some are not provided. For example, correlational or cross-correlational research is omitted and is not discussed in Section 3, but is used as a statistical example in the last section.

Examples utilized were appropriate and associated with terms adding value to the learning. The tables that included differentiation between types of statistical tests along with a parametric/nonparametric table were useful and relevant.

The purpose to the text and how to use this guide book is stated clearly and is established up front. The author is also very clear regarding the skill level of the user. Adding to the clarity are the tables with terms, definitions, and examples to help the reader unpack the concepts. The content related to the terms was succinct, direct, and clear. Many times examples or figures were used to supplement the narrative.

The text is consistent throughout from contents to references. Within each section of the text, the introductory paragraph under each section provides a clear understanding regarding what will be discussed in each section. The layout is consistent for each section and easy to follow.

The contents are visible and address each section of the text. A total of seven sections, including a reference section, is in the contents. Each section is outlined by what will be discussed in the contents. In addition, within each section, a heading is provided to direct the reader to the subtopic under each section.

The text is well-organized and segues appropriately. I would have liked to have seen an introductory section giving a narrative overview of what is in each section. This would provide the reader with the ability to get a preliminary glimpse into each upcoming sections and topics that are covered.

The book was easy to navigate and well-organized. Examples are presented in one color, links in another and last, figures and tables. The visuals supplemented the reading and placed appropriately. This provides an opportunity for the reader to unpack the reading by use of visuals and examples.

No significant grammatical errors.

The text is not offensive or culturally insensitive. Examples were inclusive of various races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

This quick guide is a beneficial text to assist in unpacking the learning related to quantitative statistics. I would use this book to complement my instruction and lessons, or use this book as a main text with supplemental statistical problems and formulas. References to statistical programs were appropriate and were useful. The text did exactly what was stated up front in that it is a direct guide to quantitative statistics. It is well-written and to the point with content areas easy to locate by topic.

Reviewed by Sarah Capello, Assistant Professor, Radford University on 1/18/22

The text claims to provide "quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences," which it does. There is no index or glossary, although vocabulary words are bolded and defined throughout the text. read more

The text claims to provide "quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences," which it does. There is no index or glossary, although vocabulary words are bolded and defined throughout the text.

The content is mostly accurate. I would have preferred a few nuances to be hashed out a bit further to avoid potential reader confusion or misunderstanding of the concepts presented.

The content is current; however, some of the references cited in the text are outdated. Newer editions of those texts exist.

The text is very accessible and readable for a variety of audiences. Key terms are well-defined.

There are no content discrepancies within the text. The author even uses similarly shaped graphics for recurring purposes throughout the text (e.g., arrow call outs for further reading, rectangle call outs for examples).

The content is chunked nicely by topics and sections. If it were used for a course, it would be easy to assign different sections of the text for homework, etc. without confusing the reader if the instructor chose to present the content in a different order.

The author follows the structure of the research process. The organization of the text is easy to follow and comprehend.

All of the supplementary images (e.g., tables and figures) were beneficial to the reader and enhanced the text.

There are no significant grammatical errors.

I did not find any culturally offensive or insensitive references in the text.

This text does the difficult job of introducing the complicated concepts and processes of quantitative research in a quick and easy reference guide fairly well. I would not depend solely on this text to teach students about quantitative research, but it could be a good jumping off point for those who have no prior knowledge on this subject or those who need a gentle introduction before diving in to more advanced and complex readings of quantitative research methods.

Reviewed by J. Marlie Henry, Adjunct Faculty, University of Saint Francis on 12/9/21

Considering the length of this guide, this does a good job of addressing major areas that typically need to be addressed. There is a contents section. The guide does seem to be organized accordingly with appropriate alignment and logical flow of... read more

Considering the length of this guide, this does a good job of addressing major areas that typically need to be addressed. There is a contents section. The guide does seem to be organized accordingly with appropriate alignment and logical flow of thought. There is no glossary but, for a guide of this length, a glossary does not seem like it would enhance the guide significantly.

The content is relatively accurate. Expanding the content a bit more or explaining that the methods and designs presented are not entirely inclusive would help. As there are different schools of thought regarding what should/should not be included in terms of these designs and methods, simply bringing attention to that and explaining a bit more would help.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

This content needs to be updated. Most of the sources cited are seven or more years old. Even more, it would be helpful to see more currently relevant examples. Some of the source authors such as Andy Field provide very interesting and dynamic instruction in general, but they have much more current information available.

The language used is clear and appropriate. Unnecessary jargon is not used. The intent is clear- to communicate simply in a straightforward manner.

The guide seems to be internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. There do not seem to be issues in this area. Terminology is internally consistent.

For a guide of this length, the author structured this logically into sections. This guide could be adopted in whole or by section with limited modifications. Courses with fewer than seven modules could also logically group some of the sections.

This guide does present with logical organization. The topics presented are conceptually sequenced in a manner that helps learners build logically on prior conceptualization. This also provides a simple conceptual framework for instructors to guide learners through the process.

Interface rating: 4

The visuals themselves are simple, but they are clear and understandable without distracting the learner. The purpose is clear- that of learning rather than visuals for the sake of visuals. Likewise, navigation is clear and without issues beyond a broken link (the last source noted in the references).

This guide seems to be free of grammatical errors.

It would be interesting to see more cultural integration in a guide of this nature, but the guide is not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. The language used seems to be consistent with APA's guidelines for unbiased language.

Reviewed by Heng Yu-Ku, Professor, University of Northern Colorado on 5/13/21

The text covers all areas and ideas appropriately and provides practical tables, charts, and examples throughout the text. I would suggest the author also provides a complete research proposal at the end of Section 3 (page 10) and a comprehensive... read more

The text covers all areas and ideas appropriately and provides practical tables, charts, and examples throughout the text. I would suggest the author also provides a complete research proposal at the end of Section 3 (page 10) and a comprehensive research study as an Appendix after section 7 (page 26) to help readers comprehend information better.

For the most part, the content is accurate and unbiased. However, the author only includes four types of research designs used on the social sciences that contain quantitative elements: 1. Mixed method, 2) Case study, 3) Quasi-experiment, and 3) Action research. I wonder why the correlational research is not included as another type of quantitative research design as it has been introduced and emphasized in section 6 by the author.

I believe the content is up-to-date and that necessary updates will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement.

The text is easy to read and provides adequate context for any technical terminology used. However, the author could provide more detailed information about estimating the minimum sample size but not just refer the readers to use the online sample calculators at a different website.

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework. The author provides the right amount of information with additional information or resources for the readers.

The text includes seven sections. Therefore, it is easier for the instructor to allocate or divide the content into different weeks of instruction within the course.

Yes, the topics in the text are presented in a logical and clear fashion. The author provides clear and precise terminologies, summarizes important content in Table or Figure forms, and offers examples in each section for readers to check their understanding.

The interface of the book is consistent and clear, and all the images and charts provided in the book are appropriate. However, I did encounter some navigation problems as a couple of links are not working or requires permission to access those (pages 10 and 27).

No grammatical errors were found.

No culturally incentive or offensive in its language and the examples provided were found.

As the book title stated, this book provides “A Quick Guide to Quantitative Research in Social Science. It offers easy-to-read information and introduces the readers to the research process, such as research questions, research paradigms, research process, research designs, research methods, data collection, data analysis, and data discussion. However, some links are not working or need permissions to access them (pages 10 and 27).

Reviewed by Hsiao-Chin Kuo, Assistant Professor, Northeastern Illinois University on 4/26/21, updated 4/28/21

As a quick guide, it covers basic concepts related to quantitative research. It starts with WHY quantitative research with regard to asking research questions and considering research paradigms, then provides an overview of research design and... read more

As a quick guide, it covers basic concepts related to quantitative research. It starts with WHY quantitative research with regard to asking research questions and considering research paradigms, then provides an overview of research design and process, discusses methods, data collection and analysis, and ends with writing a research report. It also identifies its target readers/users as those begins to explore quantitative research. It would be helpful to include more examples for readers/users who are new to quantitative research.

Its content is mostly accurate and no bias given its nature as a quick guide. Yet, it is also quite simplified, such as its explanations of mixed methods, case study, quasi-experimental research, and action research. It provides resources for extended reading, yet more recent works will be helpful.

The book is relevant given its nature as a quick guide. It would be helpful to provide more recent works in its resources for extended reading, such as the section for Survey Research (p. 12). It would also be helpful to include more information to introduce common tools and software for statistical analysis.

The book is written with clear and understandable language. Important terms and concepts are presented with plain explanations and examples. Figures and tables are also presented to support its clarity. For example, Table 4 (p. 20) gives an easy-to-follow overview of different statistical tests.

The framework is very consistent with key points, further explanations, examples, and resources for extended reading. The sample studies are presented following the layout of the content, such as research questions, design and methods, and analysis. These examples help reinforce readers' understanding of these common research elements.

The book is divided into seven chapters. Each chapter clearly discusses an aspect of quantitative research. It can be easily divided into modules for a class or for a theme in a research method class. Chapters are short and provides additional resources for extended reading.

The topics in the chapters are presented in a logical and clear structure. It is easy to follow to a degree. Though, it would be also helpful to include the chapter number and title in the header next to its page number.

The text is easy to navigate. Most of the figures and tables are displayed clearly. Yet, there are several sections with empty space that is a bit confusing in the beginning. Again, it can be helpful to include the chapter number/title next to its page number.

Grammatical Errors rating: 4

No major grammatical errors were found.

There are no cultural insensitivities noted.

Given the nature and purpose of this book, as a quick guide, it provides readers a quick reference for important concepts and terms related to quantitative research. Because this book is quite short (27 pages), it can be used as an overview/preview about quantitative research. Teacher's facilitation/input and extended readings will be needed for a deeper learning and discussion about aspects of quantitative research.

Reviewed by Yang Cheng, Assistant Professor, North Carolina State University on 1/6/21

It covers the most important topics such as research progress, resources, measurement, and analysis of the data. read more

It covers the most important topics such as research progress, resources, measurement, and analysis of the data.

The book accurately describes the types of research methods such as mixed-method, quasi-experiment, and case study. It talks about the research proposal and key differences between statistical analyses as well.

The book pinpointed the significance of running a quantitative research method and its relevance to the field of social science.

The book clearly tells us the differences between types of quantitative methods and the steps of running quantitative research for students.

The book is consistent in terms of terminologies such as research methods or types of statistical analysis.

It addresses the headlines and subheadlines very well and each subheading should be necessary for readers.

The book was organized very well to illustrate the topic of quantitative methods in the field of social science.

The pictures within the book could be further developed to describe the key concepts vividly.

The textbook contains no grammatical errors.

It is not culturally offensive in any way.

Overall, this is a simple and quick guide for this important topic. It should be valuable for undergraduate students who would like to learn more about research methods.

Reviewed by Pierre Lu, Associate Professor, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley on 11/20/20

As a quick guide to quantitative research in social sciences, the text covers most ideas and areas. read more

As a quick guide to quantitative research in social sciences, the text covers most ideas and areas.

Mostly accurate content.

As a quick guide, content is highly relevant.

Succinct and clear.

Internally, the text is consistent in terms of terminology used.

The text is easily and readily divisible into smaller sections that can be used as assignments.

I like that there are examples throughout the book.

Easy to read. No interface/ navigation problems.

No grammatical errors detected.

I am not aware of the culturally insensitive description. After all, this is a methodology book.

I think the book has potential to be adopted as a foundation for quantitative research courses, or as a review in the first weeks in advanced quantitative course.

Reviewed by Sarah Fischer, Assistant Professor, Marymount University on 7/31/20

It is meant to be an overview, but it incredibly condensed and spends almost no time on key elements of statistics (such as what makes research generalizable, or what leads to research NOT being generalizable). read more

It is meant to be an overview, but it incredibly condensed and spends almost no time on key elements of statistics (such as what makes research generalizable, or what leads to research NOT being generalizable).

Content Accuracy rating: 1

Contains VERY significant errors, such as saying that one can "accept" a hypothesis. (One of the key aspect of hypothesis testing is that one either rejects or fails to reject a hypothesis, but NEVER accepts a hypothesis.)

Very relevant to those experiencing the research process for the first time. However, it is written by someone working in the natural sciences but is a text for social sciences. This does not explain the errors, but does explain why sometimes the author assumes things about the readers ("hail from more subjectivist territory") that are likely not true.

Clarity rating: 3

Some statistical terminology not explained clearly (or accurately), although the author has made attempts to do both.

Very consistently laid out.

Chapters are very short yet also point readers to outside texts for additional information. Easy to follow.

Generally logically organized.

Easy to navigate, images clear. The additional sources included need to linked to.

Minor grammatical and usage errors throughout the text.

Makes efforts to be inclusive.

The idea of this book is strong--short guides like this are needed. However, this book would likely be strengthened by a revision to reduce inaccuracies and improve the definitions and technical explanations of statistical concepts. Since the book is specifically aimed at the social sciences, it would also improve the text to have more examples that are based in the social sciences (rather than the health sciences or the arts).

Reviewed by Michelle Page, Assistant Professor, Worcester State University on 5/30/20

This text is exactly intended to be what it says: A quick guide. A basic outline of quantitative research processes, akin to cliff notes. The content provides only the essentials of a research process and contains key terms. A student or new... read more

This text is exactly intended to be what it says: A quick guide. A basic outline of quantitative research processes, akin to cliff notes. The content provides only the essentials of a research process and contains key terms. A student or new researcher would not be able to use this as a stand alone guide for quantitative pursuits without having a supplemental text that explains the steps in the process more comprehensively. The introduction does provide this caveat.

Content Accuracy rating: 3

There are no biases or errors that could be distinguished; however, it’s simplicity in content, although accurate for an outline of process, may lack a conveyance of the deeper meanings behind the specific processes explained about qualitative research.

The content is outlined in traditional format to highlight quantitative considerations for formatting research foundational pieces. The resources/references used to point the reader to literature sources can be easily updated with future editions.

The jargon in the text is simple to follow and provides adequate context for its purpose. It is simplified for its intention as a guide which is appropriate.

Each section of the text follows a consistent flow. Explanation of the research content or concept is defined and then a connection to literature is provided to expand the readers understanding of the section’s content. Terminology is consistent with the qualitative process.

As an “outline” and guide, this text can be used to quickly identify the critical parts of the quantitative process. Although each section does not provide deeper content for meaningful use as a stand alone text, it’s utility would be excellent as a reference for a course and can be used as an content guide for specific research courses.

The text’s outline and content are aligned and are in a logical flow in terms of the research considerations for quantitative research.

The only issue that the format was not able to provide was linkable articles. These would have to be cut and pasted into a browser. Functional clickable links in a text are very successful at leading the reader to the supplemental material.

No grammatical errors were noted.

This is a very good outline “guide” to help a new or student researcher to demystify the quantitative process. A successful outline of any process helps to guide work in a logical and systematic way. I think this simple guide is a great adjunct to more substantial research context.

Table of Contents

- Section 1: What will this resource do for you?

- Section 2: Why are you thinking about numbers? A discussion of the research question and paradigms.

- Section 3: An overview of the Research Process and Research Designs

- Section 4: Quantitative Research Methods

- Section 5: the data obtained from quantitative research

- Section 6: Analysis of data

- Section 7: Discussing your Results

Ancillary Material

About the book.

This resource is intended as an easy-to-use guide for anyone who needs some quick and simple advice on quantitative aspects of research in social sciences, covering subjects such as education, sociology, business, nursing. If you area qualitative researcher who needs to venture into the world of numbers, or a student instructed to undertake a quantitative research project despite a hatred for maths, then this booklet should be a real help.

The booklet was amended in 2022 to take into account previous review comments.

About the Contributors

Christine Davies , Ph.D

Contribute to this Page

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods

Published on June 12, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Quantitative research is the process of collecting and analyzing numerical data. It can be used to find patterns and averages, make predictions, test causal relationships, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative research is the opposite of qualitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio).

Quantitative research is widely used in the natural and social sciences: biology, chemistry, psychology, economics, sociology, marketing, etc.

- What is the demographic makeup of Singapore in 2020?

- How has the average temperature changed globally over the last century?

- Does environmental pollution affect the prevalence of honey bees?

- Does working from home increase productivity for people with long commutes?

Table of contents

Quantitative research methods, quantitative data analysis, advantages of quantitative research, disadvantages of quantitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about quantitative research.

You can use quantitative research methods for descriptive, correlational or experimental research.

- In descriptive research , you simply seek an overall summary of your study variables.

- In correlational research , you investigate relationships between your study variables.

- In experimental research , you systematically examine whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between variables.

Correlational and experimental research can both be used to formally test hypotheses , or predictions, using statistics. The results may be generalized to broader populations based on the sampling method used.

To collect quantitative data, you will often need to use operational definitions that translate abstract concepts (e.g., mood) into observable and quantifiable measures (e.g., self-ratings of feelings and energy levels).

| Research method | How to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Control or manipulate an to measure its effect on a dependent variable. | To test whether an intervention can reduce procrastination in college students, you give equal-sized groups either a procrastination intervention or a comparable task. You compare self-ratings of procrastination behaviors between the groups after the intervention. | |

| Ask questions of a group of people in-person, over-the-phone or online. | You distribute with rating scales to first-year international college students to investigate their experiences of culture shock. | |

| (Systematic) observation | Identify a behavior or occurrence of interest and monitor it in its natural setting. | To study college classroom participation, you sit in on classes to observe them, counting and recording the prevalence of active and passive behaviors by students from different backgrounds. |

| Secondary research | Collect data that has been gathered for other purposes e.g., national surveys or historical records. | To assess whether attitudes towards climate change have changed since the 1980s, you collect relevant questionnaire data from widely available . |

Note that quantitative research is at risk for certain research biases , including information bias , omitted variable bias , sampling bias , or selection bias . Be sure that you’re aware of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data to prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once data is collected, you may need to process it before it can be analyzed. For example, survey and test data may need to be transformed from words to numbers. Then, you can use statistical analysis to answer your research questions .

Descriptive statistics will give you a summary of your data and include measures of averages and variability. You can also use graphs, scatter plots and frequency tables to visualize your data and check for any trends or outliers.

Using inferential statistics , you can make predictions or generalizations based on your data. You can test your hypothesis or use your sample data to estimate the population parameter .

First, you use descriptive statistics to get a summary of the data. You find the mean (average) and the mode (most frequent rating) of procrastination of the two groups, and plot the data to see if there are any outliers.

You can also assess the reliability and validity of your data collection methods to indicate how consistently and accurately your methods actually measured what you wanted them to.

Quantitative research is often used to standardize data collection and generalize findings . Strengths of this approach include:

- Replication

Repeating the study is possible because of standardized data collection protocols and tangible definitions of abstract concepts.

- Direct comparisons of results

The study can be reproduced in other cultural settings, times or with different groups of participants. Results can be compared statistically.

- Large samples

Data from large samples can be processed and analyzed using reliable and consistent procedures through quantitative data analysis.

- Hypothesis testing

Using formalized and established hypothesis testing procedures means that you have to carefully consider and report your research variables, predictions, data collection and testing methods before coming to a conclusion.

Despite the benefits of quantitative research, it is sometimes inadequate in explaining complex research topics. Its limitations include:

- Superficiality

Using precise and restrictive operational definitions may inadequately represent complex concepts. For example, the concept of mood may be represented with just a number in quantitative research, but explained with elaboration in qualitative research.

- Narrow focus

Predetermined variables and measurement procedures can mean that you ignore other relevant observations.

- Structural bias

Despite standardized procedures, structural biases can still affect quantitative research. Missing data , imprecise measurements or inappropriate sampling methods are biases that can lead to the wrong conclusions.

- Lack of context

Quantitative research often uses unnatural settings like laboratories or fails to consider historical and cultural contexts that may affect data collection and results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research, you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Quantitative Research? | Definition, Uses & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved August 18, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/quantitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, descriptive statistics | definitions, types, examples, inferential statistics | an easy introduction & examples, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

S371 Social Work Research - Jill Chonody: What is Quantitative Research?

- Choosing a Topic

- Choosing Search Terms

- What is Quantitative Research?

- Requesting Materials

Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences

This page is courtesy of University of Southern California: http://libguides.usc.edu/content.php?pid=83009&sid=615867

Quantitative methods emphasize objective measurements and the statistical, mathematical, or numerical analysis of data collected through polls, questionnaires, and surveys, or by manipulating pre-existing statistical data using computational techniques . Quantitative research focuses on gathering numerical data and generalizing it across groups of people or to explain a particular phenomenon.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Muijs, Daniel. Doing Quantitative Research in Education with SPSS . 2nd edition. London: SAGE Publications, 2010.

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Your goal in conducting quantitative research study is to determine the relationship between one thing [an independent variable] and another [a dependent or outcome variable] within a population. Quantitative research designs are either descriptive [subjects usually measured once] or experimental [subjects measured before and after a treatment]. A descriptive study establishes only associations between variables; an experimental study establishes causality.

Quantitative research deals in numbers, logic, and an objective stance. Quantitative research focuses on numberic and unchanging data and detailed, convergent reasoning rather than divergent reasoning [i.e., the generation of a variety of ideas about a research problem in a spontaneous, free-flowing manner].

Its main characteristics are :

- The data is usually gathered using structured research instruments.

- The results are based on larger sample sizes that are representative of the population.

- The research study can usually be replicated or repeated, given its high reliability.

- Researcher has a clearly defined research question to which objective answers are sought.

- All aspects of the study are carefully designed before data is collected.

- Data are in the form of numbers and statistics, often arranged in tables, charts, figures, or other non-textual forms.

- Project can be used to generalize concepts more widely, predict future results, or investigate causal relationships.

- Researcher uses tools, such as questionnaires or computer software, to collect numerical data.

The overarching aim of a quantitative research study is to classify features, count them, and construct statistical models in an attempt to explain what is observed.

Things to keep in mind when reporting the results of a study using quantiative methods :

- Explain the data collected and their statistical treatment as well as all relevant results in relation to the research problem you are investigating. Interpretation of results is not appropriate in this section.

- Report unanticipated events that occurred during your data collection. Explain how the actual analysis differs from the planned analysis. Explain your handling of missing data and why any missing data does not undermine the validity of your analysis.

- Explain the techniques you used to "clean" your data set.

- Choose a minimally sufficient statistical procedure ; provide a rationale for its use and a reference for it. Specify any computer programs used.

- Describe the assumptions for each procedure and the steps you took to ensure that they were not violated.

- When using inferential statistics , provide the descriptive statistics, confidence intervals, and sample sizes for each variable as well as the value of the test statistic, its direction, the degrees of freedom, and the significance level [report the actual p value].

- Avoid inferring causality , particularly in nonrandomized designs or without further experimentation.

- Use tables to provide exact values ; use figures to convey global effects. Keep figures small in size; include graphic representations of confidence intervals whenever possible.

- Always tell the reader what to look for in tables and figures .

NOTE: When using pre-existing statistical data gathered and made available by anyone other than yourself [e.g., government agency], you still must report on the methods that were used to gather the data and describe any missing data that exists and, if there is any, provide a clear explanation why the missing datat does not undermine the validity of your final analysis.

Babbie, Earl R. The Practice of Social Research . 12th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage, 2010; Brians, Craig Leonard et al. Empirical Political Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods . 8th ed. Boston, MA: Longman, 2011; McNabb, David E. Research Methods in Public Administration and Nonprofit Management: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches . 2nd ed. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008; Quantitative Research Methods . Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Singh, Kultar. Quantitative Social Research Methods . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2007.

Basic Research Designs for Quantitative Studies

Before designing a quantitative research study, you must decide whether it will be descriptive or experimental because this will dictate how you gather, analyze, and interpret the results. A descriptive study is governed by the following rules: subjects are generally measured once; the intention is to only establish associations between variables; and, the study may include a sample population of hundreds or thousands of subjects to ensure that a valid estimate of a generalized relationship between variables has been obtained. An experimental design includes subjects measured before and after a particular treatment, the sample population may be very small and purposefully chosen, and it is intended to establish causality between variables. Introduction The introduction to a quantitative study is usually written in the present tense and from the third person point of view. It covers the following information:

- Identifies the research problem -- as with any academic study, you must state clearly and concisely the research problem being investigated.

- Reviews the literature -- review scholarship on the topic, synthesizing key themes and, if necessary, noting studies that have used similar methods of inquiry and analysis. Note where key gaps exist and how your study helps to fill these gaps or clarifies existing knowledge.

- Describes the theoretical framework -- provide an outline of the theory or hypothesis underpinning your study. If necessary, define unfamiliar or complex terms, concepts, or ideas and provide the appropriate background information to place the research problem in proper context [e.g., historical, cultural, economic, etc.].

Methodology The methods section of a quantitative study should describe how each objective of your study will be achieved. Be sure to provide enough detail to enable the reader can make an informed assessment of the methods being used to obtain results associated with the research problem. The methods section should be presented in the past tense.

- Study population and sampling -- where did the data come from; how robust is it; note where gaps exist or what was excluded. Note the procedures used for their selection;

- Data collection – describe the tools and methods used to collect information and identify the variables being measured; describe the methods used to obtain the data; and, note if the data was pre-existing [i.e., government data] or you gathered it yourself. If you gathered it yourself, describe what type of instrument you used and why. Note that no data set is perfect--describe any limitations in methods of gathering data.

- Data analysis -- describe the procedures for processing and analyzing the data. If appropriate, describe the specific instruments of analysis used to study each research objective, including mathematical techniques and the type of computer software used to manipulate the data.

Results The finding of your study should be written objectively and in a succinct and precise format. In quantitative studies, it is common to use graphs, tables, charts, and other non-textual elements to help the reader understand the data. Make sure that non-textual elements do not stand in isolation from the text but are being used to supplement the overall description of the results and to help clarify key points being made. Further information about how to effectively present data using charts and graphs can be found here .

- Statistical analysis -- how did you analyze the data? What were the key findings from the data? The findings should be present in a logical, sequential order. Describe but do not interpret these trends or negative results; save that for the discussion section. The results should be presented in the past tense.

Discussion Discussions should be analytic, logical, and comprehensive. The discussion should meld together your findings in relation to those identified in the literature review, and placed within the context of the theoretical framework underpinning the study. The discussion should be presented in the present tense.

- Interpretation of results -- reiterate the research problem being investigated and compare and contrast the findings with the research questions underlying the study. Did they affirm predicted outcomes or did the data refute it?

- Description of trends, comparison of groups, or relationships among variables -- describe any trends that emerged from your analysis and explain all unanticipated and statistical insignificant findings.

- Discussion of implications – what is the meaning of your results? Highlight key findings based on the overall results and note findings that you believe are important. How have the results helped fill gaps in understanding the research problem?

- Limitations -- describe any limitations or unavoidable bias in your study and, if necessary, note why these limitations did not inhibit effective interpretation of the results.

Conclusion End your study by to summarizing the topic and provide a final comment and assessment of the study.

- Summary of findings – synthesize the answers to your research questions. Do not report any statistical data here; just provide a narrative summary of the key findings and describe what was learned that you did not know before conducting the study.

- Recommendations – if appropriate to the aim of the assignment, tie key findings with policy recommendations or actions to be taken in practice.

- Future research – note the need for future research linked to your study’s limitations or to any remaining gaps in the literature that were not addressed in your study.

Black, Thomas R. Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Research Design, Measurement and Statistics . London: Sage, 1999; Gay,L. R. and Peter Airasain. Educational Research: Competencies for Analysis and Applications . 7th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merril Prentice Hall, 2003; Hector, Anestine. An Overview of Quantitative Research in Compostion and TESOL . Department of English, Indiana University of Pennsylvania; Hopkins, Will G. “Quantitative Research Design.” Sportscience 4, 1 (2000); A Strategy for Writing Up Research Results . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Nenty, H. Johnson. "Writing a Quantitative Research Thesis." International Journal of Educational Science 1 (2009): 19-32; Ouyang, Ronghua (John). Basic Inquiry of Quantitative Research . Kennesaw State University.

- << Previous: Finding Quantitative Research

- Next: Databases >>

- Last Updated: Jul 11, 2023 1:03 PM

- URL: https://libguides.iun.edu/S371socialworkresearch

Quantitative and Qualitative Research

- I NEED TO . . .

What is Quantitative Research?

- What is Qualitative Research?

- Quantitative vs Qualitative

- Step 1: Accessing CINAHL

- Step 2: Create a Keyword Search

- Step 3: Create a Subject Heading Search

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 1-3 for Second Concept

- Step 5: Repeat Steps 1-3 for Quantitative Terms

- Step 6: Combining All Searches

- Step 7: Adding Limiters

- Step 8: Save Your Search!

- What Kind of Article is This?

- More Research Help This link opens in a new window

Quantitative methodology is the dominant research framework in the social sciences. It refers to a set of strategies, techniques and assumptions used to study psychological, social and economic processes through the exploration of numeric patterns . Quantitative research gathers a range of numeric data. Some of the numeric data is intrinsically quantitative (e.g. personal income), while in other cases the numeric structure is imposed (e.g. ‘On a scale from 1 to 10, how depressed did you feel last week?’). The collection of quantitative information allows researchers to conduct simple to extremely sophisticated statistical analyses that aggregate the data (e.g. averages, percentages), show relationships among the data (e.g. ‘Students with lower grade point averages tend to score lower on a depression scale’) or compare across aggregated data (e.g. the USA has a higher gross domestic product than Spain). Quantitative research includes methodologies such as questionnaires, structured observations or experiments and stands in contrast to qualitative research. Qualitative research involves the collection and analysis of narratives and/or open-ended observations through methodologies such as interviews, focus groups or ethnographies.

Coghlan, D., Brydon-Miller, M. (2014). The SAGE encyclopedia of action research (Vols. 1-2). London, : SAGE Publications Ltd doi: 10.4135/9781446294406

What is the purpose of quantitative research?

The purpose of quantitative research is to generate knowledge and create understanding about the social world. Quantitative research is used by social scientists, including communication researchers, to observe phenomena or occurrences affecting individuals. Social scientists are concerned with the study of people. Quantitative research is a way to learn about a particular group of people, known as a sample population. Using scientific inquiry, quantitative research relies on data that are observed or measured to examine questions about the sample population.

Allen, M. (2017). The SAGE encyclopedia of communication research methods (Vols. 1-4). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc doi: 10.4135/9781483381411

How do I know if the study is a quantitative design? What type of quantitative study is it?

Quantitative Research Designs: Descriptive non-experimental, Quasi-experimental or Experimental?

Studies do not always explicitly state what kind of research design is being used. You will need to know how to decipher which design type is used. The following video will help you determine the quantitative design type.

- << Previous: I NEED TO . . .

- Next: What is Qualitative Research? >>

- Last Updated: Aug 14, 2024 3:26 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/quantitative_and_qualitative_research

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

What is social science?

Quantitative research.

Quantitative research can measure and describe whole societies, or institutions, organisations or groups of individuals that are part of them. The strength of quantitative methods is that they can provide vital information about a society or community, through surveys, examinations, records or censuses, that no individual could obtain by observation.

Quantitative methodologies

Some of the most common quantitative research methodologies are described here. These methodologies are widely used in research funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Cross-sectional studies

Cross-sectional studies are surveys undertaken at one point in time, rather like a photo taken by a camera. If the same or similar survey is repeated, we can get good measures of how society is changing.

Longitudinal studies

Longitudinal studies follow the same respondents over an extended period of time. They can employ both qualitative and quantitative research methods, and they follow the same group of people over time. For example, the Millennium Cohort Study has been keeping track of more than 11,000 children born between 2000 and 2002. Some of its many findings have shown how childhood factors such as poverty and birth weight can affect health and success at school as children get older.

Opinion polls

An opinion poll is a form of survey designed to measure the opinions of a target population about an issue, such as support for political parties and views about crime and justice, the economy or the environment.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires collect data in a standardised way, so that useful summaries can be made about large groups of respondents, such as the proportion of all young people of a given age who are bullied. Usually most questions are ‘closed response’, where respondents are given a range of options to choose from. Researchers have to be careful that the questions are not ‘leading’, that the options are comprehensive (they cover every possible answer) and are mutually exclusive, so that only one answer is correct for any respondent.

Social attitude surveys

Social attitude surveys ask more general questions about beliefs and behaviour, for example, how often people go to church, how much trust they have in the police force, whether they think children need a strict upbringing, how content they are with their life, how often they see other family members, and whether they are in employment.

Surveys and censuses

A census is a survey of everyone in the population. Because of the vast number of respondents, they are very expensive to organise. Governments now depend much more on sample surveys and administrative records, for example those created by a stay in hospital or tax returns. Surveys use a questionnaire to investigate respondents in a sample. Samples are chosen in such a way that they can represent a much larger population. A precise calculation can be made of how accurate the information from any sample is likely to be.

Further information

See our social science for schools resource page on the UK Government Web Archive for more information on social science methodologies.

Last updated: 31 March 2022